China’s commercial property market has been a huge winner over the past three decades, but have the virus, a slowing economy and changes in work culture created a turning point?

In early February, as the Lunar New Year holiday drew to a close and COVID-19 infections in China surged, Winnie Li found herself an unwitting participant in the world’s biggest work-from-home experiment. Li, a web developer at an e-commerce company in Shanghai, used to commute each day for up to an hour to her downtown office. Instead, she began clocking in at home.

The experiment was not an immediate success. “For the first week or two it was truly challenging,” says Li. “There were many distractions… my sons, my parents and my husband, who also began working from home. But then I started getting used to it, and even learned to enjoy it.”

Li and 200 million other office workers quickly learned an entirely new work schedule, far away from their usual workplaces in once-bustling office towers and business hubs. With desks deserted and phones silent, the abrupt change sounded alarms over the prospects of China’s commercial office space.

“I don’t think anybody really had a sense about how big an impact it was going to have on the economy, how long the lockdowns would be enforced or the potential international impact,” says James Macdonald, senior director of China research at Savills, a real estate services provider.

The uncertainties were compounded by extensive disease control measures for the few professionals returning to workplaces. In Beijing—home to some of the world’s priciest office spaces—workplaces were permitted to operate at only half capacity. Other precautions included compulsory mask-wearing, temperature checks and rigorous physical distancing between staff.

The picture that emerged from the empty office blocks and the overnight boom in remote work arrangements was that China’s office space sector headed into a period of serious uncertainty, with significant negative implications for the economy. The commercial real estate sector—including office buildings—has played a major role in China’s economic development over the past four decades. Valued by Goldman Sachs at $52 trillion in 2019, the sector remains an important foundation of the world’s second-largest economy and a key driver of growth.

Much of China’s premium office space—known in the industry as Grade A—has been built over the last 20 years, as the country’s booming economy created demand from a new generation of homegrown private companies and multinationals setting up local operations. At the same time, many of China’s older state-owned companies traded up as they became more internationally corporate in style.

Even before COVID-19 disrupted work patterns and temporarily hollowed out office towers, China’s office market faced uncertainty due to slowing economic growth and fraying ties with the US. These headwinds prompted multinationals to temper investment in local properties.

The current slump has its roots in the China-US trade war rather than COVID-19, according to Tammy Tang, China managing director at the commercial real estate organization Colliers International. In particular, US companies postponed investment as the trade war escalated. “It was a wait-and-see mentality. They were not cutting down… but because of the political situation, they were more prudent in expansion.”

Cracks appear

Commercial real estate is a slow-moving and conservative sector, but while the China-US trade tensions might have been having a negative effect the coronavirus took little time to accelerate the underlying trends. Investors turned cautious as lockdowns began to bite on economic growth. National sales of office buildings in the first two months of 2020 slumped by 40.6% year-on-year. The decline eased to 28% for the first half of the year, but still remain near historic lows.

A record number of offices were left empty in China’s first-tier city real estate markets of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Shenzhen during the first quarter of 2020, according to China Real Estate Information Corporation. Around 7 million square meters of Grade A office space—equivalent to 12 times the total space in the Shanghai Tower, China’s highest building—lay empty in the four cities by the end of March.

Macdonald from Savills says market changes did not start appearing until after China’s historic GDP (gross domestic product) contraction in the first quarter of 2020. “Landlords only started increasing rental discounts significantly in April and May. They had a sense that it wasn’t going to return to normal and they’d have to offer greater incentives to attract tenants.”

But there is also data to suggest the office market has been resilient. Vacancy rates in the four commercial hubs averaged 15.7% at the end of June, on par with the end of March and up only slightly from 15.3% at the end of last year, according to data from Colliers.

A vacancy rate under 10% is considered healthy for China’s first-tier cities but is significantly higher than other prime real estate markets. In Beijing, the percentage of unoccupied office space rose from 15.9% at the end of last year to 16.7% at the end of March, but inched down to 16.5% three months later.

Meanwhile, the average office rent in the four Chinese cities declined by an average of 3.5% from the end of March to the end of June, which was a steeper drop than the 2.2% decline from the end of 2019 to the end of March.

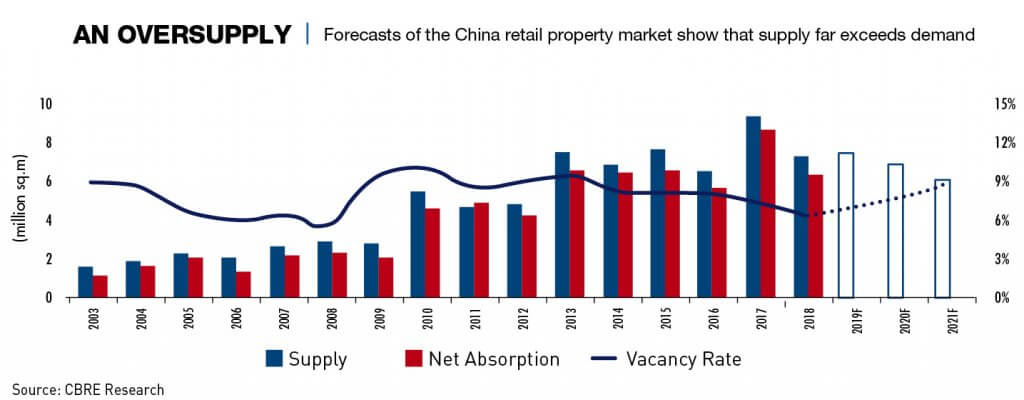

The modest declines in vacancy rates and rents in the first six months of 2020 suggest the market has weathered the pandemic fairly well. What has happened is an acceleration of trends that were apparent before COVID-19 struck. China’s property market started cooling years ago, spurred by the general economic slowdown and plentiful supply coming onto the market.

The latter factor in particularly has helped push up vacancy rates while depressing rents. Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Shenzhen had approximately 38.4 million square meters of Grade A office space by the end of June, but Macdonald forecasts another 11 million to be completed by the end of 2022. And over the same period, 18 million square meters of new office stock will be added to the existing 13.2 million square meters across the second-tier cities of Chengdu, Chongqing, Hangzhou, Tianjin, Wuhan and Xi’an, as tracked by Savills.

Demand is unlikely to absorb all the new supply in the short term, according to Macdonald. Even before COVID-19, vacancy rates had been tipped to edge higher on a combination of the extra supply and a slowing economy.

“COVID-19 hasn’t helped, though developers have postponed the handover of some projects, helping to reduce some supply pressure,” says Macdonald. He adds that the looming flood of new supply is likely to put downward pressure on rents and occupancy rates, which will lower capital values—effectively the price of whole buildings.

First-tier cities tend to fare better than lower-tier ones in digesting new office space, says Tang from Colliers. “In tier one cities where office demand is strong, the imbalance of supply and demand will recover over one-to-two years. In many second-tier cities, where supply is mostly abundant, a city-wide vacancy rate of 20-30% is common.”

There’s no place like work

The scale of remote working seen in the first half of 2020 is unprecedented, and the sense is that flexible work arrangements will leave a lasting impression on the way people work for years to come. Twitter in the US, for instance, told staff in May that they could remain out of office permanently if they desired.

But in China, the discussion never truly got off the ground. “The lockdown was relatively short-lived,” says Macdonald from Savills. “Most parts were back to normal quickly … people were in the office. It won’t revert completely back to the way it was before but won’t be too far off either.”

Tang of Colliers believes reports of the office’s demise are wide of the mark. “It is ludicrous to think that companies will not return to offices,” she says. “Anyone who says they’re not going to be in offices is naive about how company culture is built.”

Claire Stephens, consulting director at global architecture firm Gensler, says two ‘camps’ have emerged on office space. The first are multinationals challenged by the global economic downturn.

“That will impact all of their decision-making, and will mean cutting back on the size of office space and looking at alternative strategies at getting more bang for their buck. This probably means cost-conscious decisions when it comes to new real estate.”

The second group comprises companies still expanding, such as e-commerce players and those in the wider IT sector. “They’re just looking at doing it in a smarter way.”

Chinese white-collar employees have not embraced remote working with as much aplomb as their American peers either. Zhang Xiaomeng, Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior at CKGSB, found that many employees reported reduced efficiency when working from home. In a survey conducted by her team, which had 5,835 respondents, more than half reported reduced efficiency when working from home. Nearly 37% reported no difference, while less than 10% said they worked more efficiently from home.

“You can be as open-minded as you want, but Chinese still want to be face to face,” says Tang from Colliers. She adds there was less chance of a pushback from staff after their bosses asked them to return to their desks. “The Chinese management style is easier in this regard. We can’t push people, but you can say ‘please come back’ and they will.”

Traditional management thinking will also help the office retain its importance as a physical space for corporations. This is especially true of state-owned enterprises, which rely on highly structured management systems to get work done and managers who measure contribution by overtime at the desk. “You do have managers who like to see staff working,” says Savills’ Macdonald. “They don’t necessarily prioritize output but think about input in terms of number of hours worked.”

Rather than abandoning offices, the likelihood is that they will adapt. The corner office may remain the ultimate sign of success, but otherwise modern corporate workplaces could be redesigned for health and wellness in mind. Changes could range from installing touchless fixtures to implementing one-way routes around the office so staff avoid crossing in opposite directions, according to Gensler.

No disruption

The stay-at-home orders that emptied offices made real estate developers and state planners wonder about the economic impact of reduced demand for office space, given the importance of construction to the economy. The building industry is important for employing vast armies of laborers and consuming materials. It is also critical for the construction machinery and auto sectors as it drives demand for bulldozers, excavators, mobile cranes and heavy-duty trucks, while exerting an influence on energy demand.

However, a significant falloff in new office construction is unlikely. After a brief pause during the lockdowns, China’s real estate market bounced back sharply. “China is so policy-driven—when a local government says we are building a new business district, then it is going to proceed,” says Tang from Colliers. “If anything, I think we’ve seen some big projects speeded up because of COVID-19.”

Li, the Shanghai web developer, received the all-clear to return to the office in late March after eight weeks of working at home. “I felt stuck at home toward the end and was ready to go back as I missed socializing with my colleagues. But I would also like the option of working from home occasionally,” Li says.

She may get her wish. “Having that communal focal point where you can meet with colleagues and have meetings face to face is still incredibly important,” says Macdonald. “But it may not mean that you have to go into the office from nine to six, five days a week.”