With the growth of China’s economy came a host of new jobs, raising millions of people out of poverty. How are businesses cashing in on the now massive lower-middle income demographic?

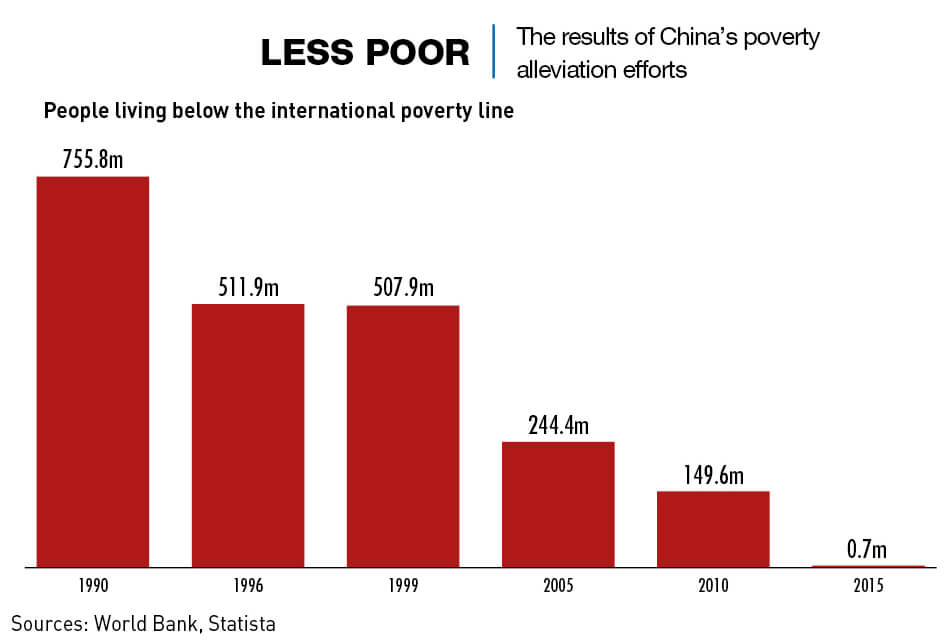

China’s war on poverty has been a success with 850 million people lifted out of poverty, resulting in a whole new class of lower-middle income consumers. Above the poverty line but not yet among the ranks of the prosperous middle class, this segment presents a huge opportunity for foreign brands and businesses.

Progress and inequality

China’s economy, growing at an average rate of around 10% a year since the late 1970s until recently, has propelled it into position as the world’s second-biggest economy and brought poverty levels down from more than 80% in 1981 to just 1.7% by the end of 2018. This makes China the first country to realize the United Nations Millennium Development Goal for poverty reduction.

Amongst the many results of this has been the creation of an urban middle class of some 400 million people who have developed an appetite for a wide range of upscale products, from luxury handbags to foreign toothpaste brands. But beyond the urban middle class, the rise in prosperity has also pushed up living standards and disposable income for hundreds of millions of people who not long ago were peasant farmers.

“China’s lower-middle class is an important sector,” says Sarah Wong, Head of Digital for McCann Health China. “And not just because of their number, but because they’re everywhere.”

Of those who have made it into the middle class, which according to data from the Pew Research Center, now accounts for 39% of China’s 1.4 billion people, the majority (75%) sit in the lower-middle income bracket. This group, with a daily spending power of between $10 and $20 (as calculated by Pew), account for just over 29% of the total population.

China’s middle-class has started to behave similarly to counterparts around the world, with one important difference: whether in the lower or upper segment of the demographic, the first priority for families when they reach a certain level of prosperity is the education and prospects of their children, because they know that upward mobility depends on knowledge and academic qualifications.

“Poverty is not just about income but low opportunity,” says Jianye Wang, a professor of economics at NYU Shanghai. “China has been and still is a dual economy between urban and rural areas.”

Roads and inroads

Beijing has invested heavily in infrastructure in the last few decades to help lift the rural population further out of poverty. According to government figures, 99.5% of villages are now linked to the outside world with paved roads, and 96.5% have at least one bus service. The luckiest rural residents find themselves close to a high-speed railway station, which means being able to get quickly to anywhere else in the country and also benefit from the growing lure of domestic tourism, says Mark Wang, a professor in Chinese social sciences at the University of Melbourne. “Chinese people want to go to beautiful places where everything is cheap. The local farmers in these areas build accommodation for tourists and find a new market for their products.”

The government has also accelerated development of online infrastructure in rural regions as part of an “Internet Plus” strategy to tackle poverty. A manifestation of this are the “Taobao Villages,” which encourage, and largely depend upon, the production of foodstuffs and other specialties for sale through China’s biggest online marketplace. According to AliResearch, as of August 2019, there were 4,310 Taobao Villages scattered across the nation.

Yang Xue, a former apple farmer in Luochuang county, Shaanxi province, has benefited greatly from this northwestern region’s increased connectivity. While the government and private industry have helped introduce sustainable farming techniques and worked to promote the apples grown by the area’s 161,000 farmers, she has learned the ropes of e-commerce and can now make upward of RMB 50,000 ($7,000) a month selling her family’s produce online.

“My parents never had much money when I was a child, but now I can make a lot as long as the market is good,” she says. “It is very good for my family and this region.”

“Infrastructure is really expanding the market, reducing transportation costs and bringing those rural, mountainous, remote populations, and more importantly their labor force, into the market,” says Jianye Wang. “They start to produce, sell and earn on the market.”

The number of internet users grew to 854 million in the first half of 2019, giving the country an internet penetration rate of 61.2%, 98.6% of which comes from mobile devices. Rural internet connectivity and the penetration of e-commerce down to the smallest and remote villages continues to grow, although still has a way to go. China’s e-commerce giants are keen to reach this sector.

“Many brands are striving to get into lower-tier cities now, but most residents far out in the rural countryside have yet to experience online shopping and deliveries take much longer to arrive,” said Wong.

China’s biggest e-commerce sites are working hard to address the problem, with JD.com employing more delivery personnel and testing drone delivery, and Alibaba’s Rural Taobao initiative hoping to expand coverage to 150,000 villages by 2021.

A population on the move

Chen Jingjing is one of the many millions who moved from rural areas to the city between 2000 and 2020. She grew up on a farm in Wuxue, in the central province of Hubei, where her parents got by growing their own food and selling the surplus at the local market. Chen and her four siblings rarely ate meat and never had new clothes. But thanks to government subsidies, Chen’s parents were able to send her and her youngest brother to university. Chen now lives in Shanghai where she makes a living as a Mandarin teacher. Since all the children have moved out of the family home, Chen’s father has also found employment as a construction worker in a nearby city.

“Overall, life is a lot better now,” she says. “Now my parents have more money, they are building a house and can buy medical insurance. But they don’t have much to spare as they still want to buy apartments for my brothers for when they marry. They take this responsibility very seriously.”

In terms of foreign brands, Chen says she gave her daughter Nestlé-owned Wyeth Nutrition milk formula when she was small and now shops at Korean lifestyle store Miniso for makeup, cheap gadgets and fun household gear, and she goes to the Japanese-owned store Uniqlo for basic clothing.

“Whether rich or poor, Chinese people’s first priority for spending is their kids,” says Mark Wang. “For education, food and everything related to the child, they will try 120% to get the best stuff.”

The secrets to success

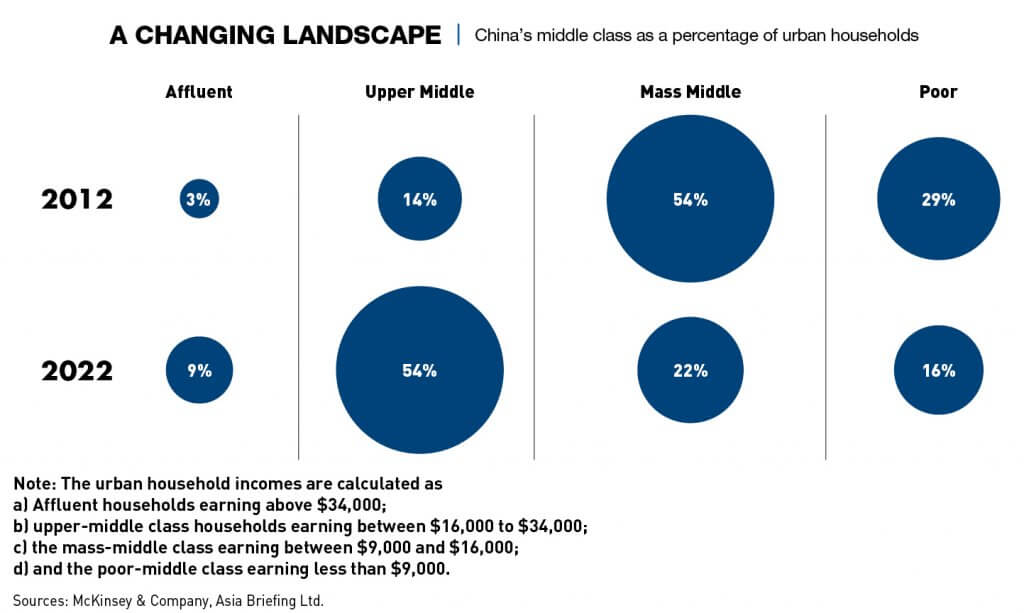

According to McKinsey, multinational brands entering China have a choice of whether to target the country’s upper-middle class (termed “mainstream consumers” by the consultancy firm and estimated to consist of a relatively modest 14 million households) or the lower-middle class (termed “value consumers” and estimated to consist of 184 million households). Those deciding on the former can more or less follow the same business model as they do in other parts of the world, while those opting for the latter need to re-engineer both their products and strategy.

The race for the lower-middle class dollar has seen many established international brands introducing entirely new products, whether it be squid on a stick at KFC or lobster-cheese flavored Lay’s chips.

One of the most famous mass market success stories is Oreo, which reinvented the classic American cookie after a disappointing start in China. As well as creating a wafer-style biscuit that was a more familiar shape and consistency for Chinese consumers, smaller, cheaper packets were introduced alongside Asia-friendly flavors like green tea. The result has seen Oreo take 46% of China’s sandwich biscuit market and 30% of its wafer biscuit market, giving Oreo its biggest combined market share anywhere in the world.

Wong says many of the foreign brands they work with also launch specific products for lower income consumers. One example is SLEK, a haircare brand from Beiersdorf, which is touting its natural credentials to grab the attention of lower-middle class consumers who are increasingly wary of chemicals in their products.

Dividing their targets by city tiers (usually a good indicator of wealth), McCann’s own research also found that consumers’ willingness to spend on imported milk formula hardly differed across tiers, with 87.5% spending on foreign milk powder in affluent first-tier cities compared to 83.5% in second, 71.9% in third and 71.1% in fourth. “Our clients don’t discriminate against lower tiers or incomes,” says Wong, adding that they target low-income consumers through the same channels as middle-income consumers, such as JD.com, Kaola, Little Red Book, Taobao and WeChat.

Chen Jingjing uses the same online shopping channels herself. In addition, she uses Kuaishou, a video-streaming platform with more than 200 million daily active users that uses an actively inclusive algorithm to give rural people, a window into the world. “I buy a lot of natural products from Kuaishou because you can see the people who are growing them and the conditions,” says Chen.

While foreign brands may find it hard to compete in areas where Chinese companies excel, such as high-tech (the top four smartphone brands are all domestic), sectors that require a high level of trust, such as food and wellness, are still dominated by foreign brands.

“Sure, you can get a lot of these products in China now,” says Shanghai-based food blogger Rachel Gouk, “but you need a lot of certification to back it up and convince people it’s safe, it’s healthy, versus the mindset that it’s better for you and can be trusted just because it’s imported. They trust that things from abroad will have a higher standard of quality.”

The bottom line

Chinese people are indeed getting richer, but at the same time the cost of living and the pressures upon them are mounting and the increase in disposable income is slowing. According to Li Shi, an economics professor at Beijing Normal University, rising household debt—much of it driven by an undeveloped welfare system that makes saving for medical expenses and old age essential—is impinging on the willingness of the middle class to spend.

Beijing is, however, keen to increase the country’s spending power through tax reforms, and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s little doubt that all efforts to ease economic pressures on both citizens and businesses will be made. Research by McKinsey predicts that many “value consumers” of the last decade will become “mainstream consumers” this year. It’s unlikely that China’s rural poor will completely disappear any time soon. Those who are able to move to the city will do so, leaving the least economically mobile behind. “Once lifted above the poverty line, around two-thirds are actively engaged in online shopping, providing tourism facilities or selling their local products,” says Mark Wang. “But another third is officially lifted above the poverty line but it’s not permanent,” he adds, explaining that this group is most commonly made up of the old, the sick and the disabled. “The fundamental issue is how can you increase the economic ability of these households?”

Opportunities abound within this increasingly widespread and diverse sector, but brands looking to cash in must tailor their products, services and messages to the places and people they seek to reach.

“Everybody has a phone these days but not everyone has a TV, so digital platforms are essential for reaching lower-income groups,” says Wong.