China dominates the global gaming industry with its massive market. What is driving this trend? Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOG) are part of China’s growing virtual entertainment culture, generating both cash and concerns about addiction and social isolation

On any given day, 200 million Chinese people are fighting monsters and minions as historical characters in an online universe far removed from the mundanity of daily life.

Close to 620 million Chinese people played online games last year—more than there are people in the European Union. China’s most popular online title, Honor of Kings is a multiplayer battle game with a user base roughly equal to the population of Brazil.

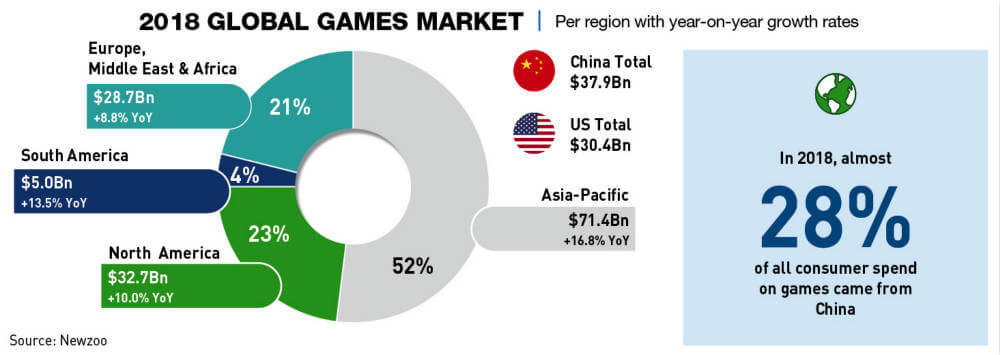

China now dominates the global gaming industry with a market worth nearly twice that of Japan’s and with nearly three and a half times as many players as the world’s second-most active gaming nation, the United States. What’s more, these Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOG) are playing a major role in China’s growing virtual entertainment culture. But surrounding this success story are also nascent worries about addiction, myopia and social isolation.

To combat this, Beijing last year introduced a new regulatory framework that created further demarcation between gaming in China and the rest of the world, and for a time froze the approval process for new games to ensure that all met the stringent control and content requirements.

“There was growing concern over the effect of video games on children and teenagers in the months leading up to the stricter regulation policy,” says Tom Wijman, senior market analyst at Newzoo. “There was also growing concern over the aggressive monetization practices used in multiple games.”

Overview

Online gaming, which mostly involves fighting and overcoming challenges in fantasy worlds, is seen as a core activity amongst two-thirds of Gen Z males—the demographic cohort after millennials—many of whom regard it as an identity-defining pass-time.

Newzoo, a games and esports analytics firm, estimates that there are now more than 2.5 billion gamers worldwide, a quarter of whom—619.5 million players—are in China. Chinese people are expected to also spend $36.5 billion on online gaming in 2019, just below the US which is forecast to spend $36.9 billion. This means China will account for roughly one-fourth of the expected global total of $152.1 billion.

Internationally, the top three computer games are League of Legends, a fantasy battle game; Minecraft, a ‘sandbox platform’ where players create their own worlds; and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, a first-person shooter game themed on counter-terror combat.

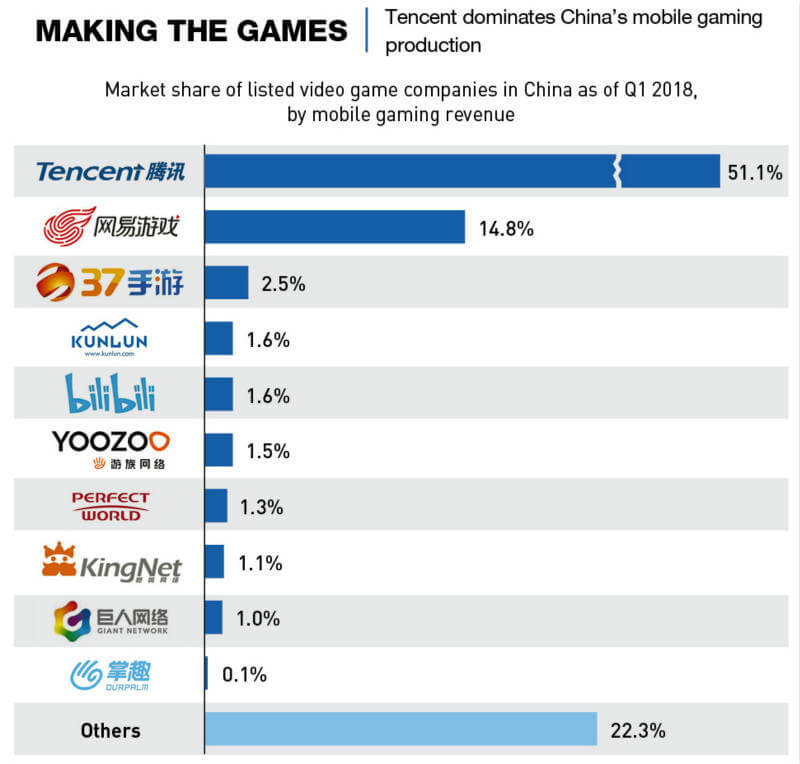

However, the most popular games in China are both from tech giant Tencent—Honor of Kings and Game for Peace, according to Turian Tan, a market analyst at IDC China’s Client System Research.

Honor of Kings is a fantasy role-player battle game modeled after League of Legends, while Game for Peace (or Peacekeeper Elite), which recently replaced PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), is a last-man-standing shooter game. Anipop stands out in third place on mobile as a casual puzzle game.

“MOBA [Multiplayer Online Battle Arena] and FPS [First-Person Shooter] games are still the biggest titles,” says Tony Xu, a reporter at Technode. “The most popular ones are League of Legends, Honor of Kings, Peacekeeper Elite, Knives Out [and] Identity V.”

While Chinese gaming habits and game preferences differ somewhat from other markets, the gap is narrowing, says Wijman. “In general, Chinese players have a stronger-than-usual preference for role-playing games. Games where the players’ status is visible are quite popular in China, such as those with a competitive ladder with a displayed rank or those that provide visible character progression.”

Profile of users in China

Mobile gaming accounts for two-thirds of the market, with computer games close behind and consoles still small in comparison.

Tan places mobile gaming at 67.6% in the first half of 2019—RMB 77.1 billion ($10.8 billion) of RMB 114.0 billion, with PC and web gaming at 27.5% and 4.5% market share respectively.

China’s 138,000 internet cafés are a key part of the country’s online gaming economy. Many people prefer to play from internet cafés rather than at home because of the more social setting, according to Wijman.

Chinese players spend between 11 and 50 hours per week on games. Core gamers, which make up the largest segment, average around 18 hours weekly. Game Analytics, an analysis platform, notes that Chinese tend to play fewer sessions but spend 48% more time in total than gamers in the rest of the world.

The economics

Tencent easily dominates the Chinese gaming industry by revenue. Game developers usually make money by offering the games for free but win their money back on in-game upgrades, with people paying for character costumes, powers or other virtual assets. Estimates from 2017 placed average spending per player at between about $1.50 to $6 a month.

Game Analytics says Chinese gamers spend less on average, but buy more often than gamers elsewhere. In sum, Chinese spend 50% more on in-app purchases than players in the rest of the world.

Last March, however, the government blocked monetization during a 10-month blackout on new releases, partly to limit addiction among young players. The freeze prevented Tencent from earning money from its popular PlayerUnknowns’ Battlegrounds (PUBG). Tencent then replaced it with a more government-friendly alternative.

“The company successfully rebranded its previously unapproved PUBG Mobile into the patriotic-themed Peacekeeper Elite while retaining essentially all the important features,” says Xu. “PUBG Mobile was unable to monetize due to its somewhat violent theme, but after the rebranding, it received no regulatory pushback.”

Still, weighed down by weak gaming revenue, Tencent reported its first quarterly profit fall in nearly 13 years in late 2018, and China’s gaming industry as a whole suffered its slowest growth since 2008.

“The top 10 game companies generated more than 90% of the total market revenue in 2018,” says Tan. “The regulations would increase this gap since small and independent producers don’t possess sufficient resource reserves when facing restricted policy on game licensing issues.”

The US is scheduled to overtake China in revenue terms in 2019 for the first time since 2015. The main drivers are console growth in the US paired with the license freeze in China, says Wijman.

Policies

Addiction fears were a factor leading the Chinese government to ban gaming consoles in 2000. But players instead flocked to computers, creating a market for PC games, and the ban on consoles was lifted in 2015.

Similar concerns over addiction and short-sightedness in children, have recently encouraged the government to further tighten oversight. Under the new regulations, restrictions are imposed on age, content, monetization and playing time.

Content that involves mahjong and poker, and many storylines or situations from China’s past are banned, as are the depiction of blood, corpses or ghosts. And time restrictions are now in force for minors.

“The game content regulations are just a clearer, and in some cases stricter, interpretation of the content rules that have been in place for nearly two decades,” says Lisa Hanson, founder and managing director of Niko Partners, a market researcher on Asia’s gaming market. “New rules include that there can be no pooling blood, no spirits rising when a character dies in a game. But for the most part the content rules exist to promote unity and support government policy.”

“The reason for tighter government regulation is to make games more in line with the core values of the [Communist] Party, which does not approve of elements such as gore, nudity and violence,” says Xu.

The authorities resumed approvals in April 2019, but they are still working through a backlog of games waiting for permission to go to market.

“Titles that ‘lack cultural value’ or ‘blindly imitate others,’ as well as those that are ‘excessively entertaining’ will be rejected,” says Xu. “The approval process will also tilt toward original high-quality games, but standards are not explained. The reasoning behind this could be to clear out low-quality copycat games that have been flooding the market, thereby making room for more well-made and innovative titles.”

An enduring stigma

Optimists reckon that gaming can foster online interactions and improve decision-making and problem-solving skills. A study last year on Fortnite, one of the most popular games in the world, took issue with the assumption that video games are socially isolating, and found that the game instead strengthens friendships and gives gamers a sense of belonging.

“Besides the fun it brings, it’s also a way to connect with people,” says Chonglin Feng, a 27-year-old gamer from the eastern city of Wuxi. “The game requires teamwork and a lot of communication. Players can invite WeChat friends to play games, which makes it an easy way to get closer with people like colleagues or clients.”

But critics fear excessive gaming steals time from real-world social interactions. They contend that gaming can be addictive, harmful to real-life relationships and taxing on families.

Several high-profile deaths over the years have spotlighted the negatives. In 2011, a man died in an internet cafe in Beijing after a sleepless three-day gaming session, and a World of Warcraft player collapsed in Shanghai in 2015 after playing 19 hours nonstop.

“Teenagers’ access to games and gambling are among the major reasons that the government is calling for stricter game industry regulation,” says Tan. “I would say we should expect more elaborate regulations regarding age control, in-game purchase and imported game content.”

The People’s Daily in 2017 labelled Honor of Kings a “poison” and a “drug.” Tencent responded swiftly by limiting access to one hour of daily play for children under 12 and two hours for those between 12 and 18.

“They are very concerned with the health and safety of young gamers, so there are requirements for anti-addiction and real name registration and restriction of use of internet cafes,” says Hanson. “There are anti-addiction mechanisms built into the development of most games now, and all of Tencent’s games have an anti-addiction component.”

A separation

Despite the concerns, gaming is definitely here to stay. Niko Partners predict China will have 767 million gamers by 2023, while the PC and mobile markets together will be worth $41 billion. Newzoo expects China to reclaim the top spot from the US in value terms in 2020.

Ironically, despite the global nature of online games, there is a clear division between the Chinese market and the rest of the world, and Beijing’s recent regulations on content and licensing play a large role in the demarcation.

“There is a significant difference between gaming in China versus any other market, for multiple reasons,” says Wijman. “First, the influence of the government leads to strong regulation on what games can be played. Content is checked on ethical grounds for potentially harmful content, for monetization practices and for violence.” Second, Wijman points out, every game in China must be published by a Chinese company, which means the top global online game developers have to partner with a local company. “For example, Blizzard works with NetEase to launch any of their games in China. Or Valve has now partnered with Perfect World to launch a Chinese version of Steam.”

The number of hours people spend online playing these games will likely grow with the industry—as will fears of their dangers and attempts to offset them. But those in the gaming community don’t necessarily share concerns about the future of gaming. “Sometimes people may spend too much time on it, but it happens more with teenagers or college students,” says Feng. “Most of my gaming friends don’t have any control problems.”