China is close to releasing a national digital currency. How would such a currency run by a central bank work? China is where paper money was first invented a thousand years ago, and it might be where paper as a proxy for value also fades from the world stage.

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), announced in August that it would soon roll out a national digital currency to replace cash. If it does, China would be the first major country to do so, and would set a trend that has the potential to upend the entire global financial structure.

Some experts have speculated that China’s digital currency will be a crypto currency similar to Bitcoin, which is built on a blockchain model allowing for vastly dispersed control and anonymous transactions, but most indications are that it will rather be a centralized currency that looks and acts much the same as what already exists in the marketplace, except in a digital form.

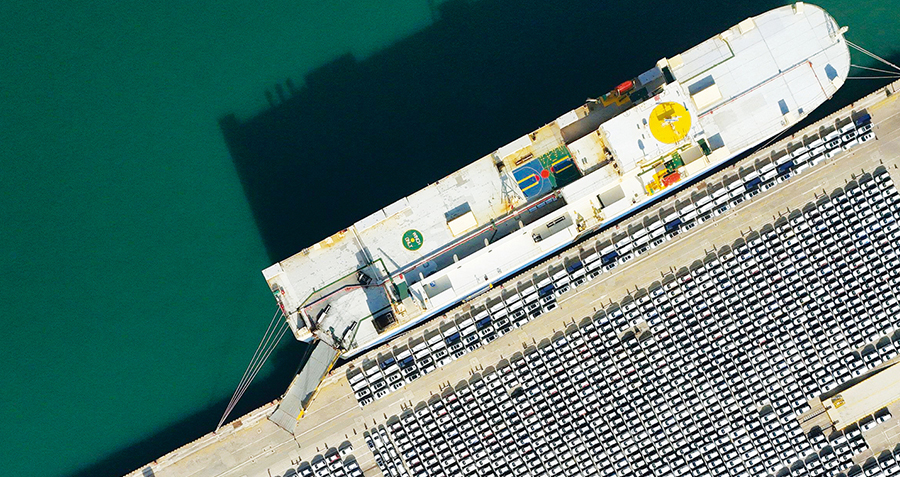

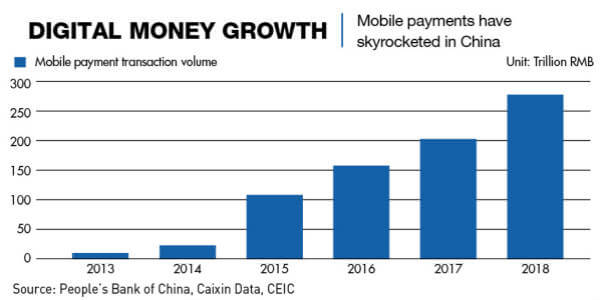

China is able to lay claim to being the birthplace of paper money, during the Song Dynasty a thousand years ago, and it may soon be where paper as a proxy for value also begins its retreat from the world stage. The country is already at the forefront of the shift away from banknotes with Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Wallet leading the way. Both services process far more digital payments than any other digital payment alternative around the world and are now a part of daily life for most Chinese people.

According to the China Daily, the number of mobile and online payment transactions in China in 2018 reached RMB 57.01 billion ($8 billion), up from RMB 23.67 billion in 2013, while the value of all transactions more than doubled to RMB 2,126.3 trillion ($297 trillion). Just about everything can now be paid for with digital payment swipes from a mobile phone, including coffee, cars and charity payments to beggars.

But an official China digital currency would take this trend to a whole new level.

Why now?

Although the concept has been in the works since 2014, the official announcement of plans to launch a digital currency came around the time that—for the first time in years—the Chinese RMB fell below the threshold of RMB 7 to the US dollar. That was in early August and was also around the time that Facebook announced its plans for a global digital currency, called Libra. There has been intense speculation in the markets as to just what the Chinese authorities are planning and how it will affect both China’s economy and that of the world.

The PBOC’s digital currency chief is Mu Changchun, who was appointed head of the central bank’s digital currency research subsidiary in September. In August, he disclosed at a forum in Beijing, that the Bank was now ready to launch a digital currency, and some experts saw the announcement as being aimed at offsetting the momentum created by Facebook’s statements around Libra.

“Where we are now is just like in a horse race, when several designated institutions are taking different technical routes for developing the digital currency and electronic payment,” Mu was quoted by the China Daily as saying. “The winner will be the one who has the best approach, accepted by the public and the market. So that is a process of market competition.”

Mu added that any digital currency must be under central bank control, and that would seem to rule out a blockchain kind of option.

Ting Lu, chief China economist at Nomura, says the main goal of a national currency would be to strengthen state control over the banking system and China’s national currency, and it would not be a crypto-like currency. “I don’t believe that any central bank in the world would allow the private sector to create money,” he says. “I don’t think the central bank is trying to compete against crypto currencies.”

Addressing the rampant speculation about a digital currency, PBOC governor Yi Gang told a news conference in September that more “research, testing, trials, assessments and risk prevention” was needed before it could be launched.

“In particular, if the [sovereign] digital currency involves cross-border use, it will involve a series of regulatory issues regarding anti-money-laundering, anti-tax evasion, anti-terrorism financing as well as know-your-client protocols,” Yi added.

A power grab

And while cross-border, international trading of a digital Chinese currency is a major consideration, the first concern for financial officials and the markets is how it would affect China’s domestic economy.

“The number one factor here is control,” says Christopher Balding, an associate professor at Fulbright University in Vietnam, who has studied China for more than a decade. According to Balding, it would provide the state with an enhanced ability to monitor private-sector companies and increase tax revenues.

“Five years ago, China was a cash-based economy,” he says. That is no longer the case. Most people, even in remote regions pay for goods through private banking systems like Alipay and WeChat Wallet. That amounts to trillions of dollars in payments.”

It would also have the impact of restricting corrupt transactions. “It is much harder to be corrupt if China understands your finances in real time,” says Balding.

Push for centralized control

Beijing has been strengthening the government’s oversight of all corporate affairs in recent years, even though the role of the state has been a key issue in the China-US trade talks over the past two years. “They are definitely trying to integrate much more with the private sector,” Balding adds.

The looming launch of Facebook’s Libra currency is one of the factors putting pressure on the PBoC to step up its plans. Libra doesn’t exist yet, but Facebook’s announcement sent shock waves through central banks around the world, because it raised for all of them the specter of a loss of control of the basic building block at the heart of the economies they oversee—money.

Libra, due to be launched in 2020, has been pitched as mirroring real-world assets, and being backed by a basket of sovereign currencies, with US dollars making up 50% of the basket. The Libra basket does not include China’s RMB, which, unlike other major world currencies, is not freely convertible.

The PBOC’s Mu Changchun said in August that China’s digital currency would “bear some similarities” to Libra, but he did not elaborate. He also said that the currency would aim to “strike a balance between anonymous payments and preventing money laundering.”

The advantage of a central bank-issued digital currency over payment platforms controlled by private companies like Alibaba and Tencent, he said, is that such commercial platforms could go bankrupt and cause users to lose money.

China UnionPay is the state-backed financial organization that provides the basis for all Chinese bank card operations and controls all bank teller machines throughout China. Its chairperson Shao Fujun, a former PBOC official, was quoted by China Daily as saying the precise form the digital currency would take was still under discussion, but added: “It will have lots of positive impacts, including tracking the money flow in economic activities and supporting making monetary policy.”

A true crypto won’t work

China would not be the first country to establish a digital currency. A number of small countries including Cambodia, Estonia and Singapore have announced plans to establish such currencies, and are at various stages along the road to launching them. None of them have so far gone as far as the Marshall Islands, a tiny country in the South Pacific with just 53,000 people and a treaty relationship with the United States.

The Marshall Islands is going all-in on a bitcoin-based currency to be called the Sovereign or SOV. It will run in parallel to the US dollar, which is currently the only legal currency in the islands.

That may make sense for the Marshall Islands, but China, the world’s second-largest economy with a population of 1.4 billion people, is an entirely different situation.

Any blockchain-based currency involves to some extent decentralization, but China’s model is the exact opposite—the centralizing of control, says Balding. “This has to do with managing risks and measuring the economy. This just gives them more information. More than anything it gives China the ability to channel resources. They can see what companies are doing.”

Beyond that is the question of what impact a Chinese digital currency could have on global finance and trade flows, and some people see it as having the potential to undermine the US dollar‘s dominance. The Chinese government has been trying for years to get the RMB accepted as an international currency, but has had only limited success.

“It [a digital currency] circumvents the global economic structure that is now in place,” says Michael Stout, a London-based cyber security and fintech expert who consults for governments. “What they are trying to do is bypass the dollar-based system.”

“When a central bank makes a play like this, they are attempting to create price equalization,” Stout adds. “It creates price stabilization between the dollar and the yuan (RMB). It’s not tied to an exchange rate. What they want to do is control the price of trade.”

The RMB exchange rate has increasingly been under pressure during 2019 to some extent because of the China-US trade war.

“China has an incentive because they can move off the dollar,” Stout says. “They [would be] no longer reliant on traders and they can shut down the blockchain if they want to. The currency allows them to operate without the oversight of the United States.”

A digital fiat currency

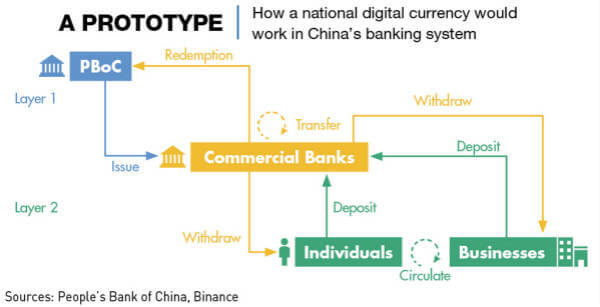

The PBoC governor, Yi Gang, said that the central bank plans to make its digital currency available through four state-owned banks—Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, China Construction Bank and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China—as well as the online payment platforms operated by tech giants Ant Financial, a unit of Alibaba, China UnionPay and Tencent.

The PBoC’s Mu said the currency would be based on a system similar to that used to produce minted money, with the PBoC producing and managing the currency, then issuing it to commercial banks and other entities, which would then circulate it to consumers.

A research report from crypto exchange Binance said that China’s digital currency will be backed 1:1 by the RMB, as well as follow a two-tiered structured system with the commercial banks, and retail market participants.

“The first tier will connect the PBoC with commercial banks for currency issuance and redemption,” Binance said. “The second layer will connect those commercial banks with the greater retail market.” Binance says that the PBoC’s system could allow fund transfers without the need for a bank account.

“The end goal for the CBDC is to display a turnover rate as high as cash while achieving ‘manageable anonymity’,” Binance said in the report. “In other words, in the first-layer network of the CBDC, real-name institutions are expected to be registered while the transfer in the second-layer network would be anonymous from the perspective of users.”

Chasing Libra

The extent to which the impending launch of the Libra could be influencing the Chinese financial authorities is not known, but it is clearly not an irrelevant factor, despite the gulf that exists between the Chinese and international financial systems. The PBoC’s research director Wang Xin, quoted by the South China Morning Post, said the Libra might reinforce the US dollar’s influence over the global financial system.

“If [Libra] is widely used for payments, cross-border payments in particular, would it be able to function like money and accordingly have a large influence on monetary policy, financial stability and the international monetary system?” Wang Xin asked at a conference in July, adding that the new digital currency could have a major impact on monetary policy and financial stability.

Stability is a strong requirement of the Chinese authorities. Economic growth has been slowing in recent years, and is forecast to fall further in 2020 due to a combination of systemic and international issues.

“A rapidly aging population, a falling birth rate, a tightening Federal Reserve and a slowing global economy have combined to put the brakes on China’s economy,” Balding says.

A digital currency could help offset some of these risks, but in some ways, China is already a long way down the road to having an economy underpinned by digital payments.

“What’s the difference between the PBoC using digital money and WeChat? Digital currencies are already used on such a wide scale that it makes no difference,” says Nomura’s Lu.

Fulbright University’s Balding agrees. “If you think of the trillions of dollars in RMB that are transacted digitally today,” he says, “they are already a cashless society.” Will China go completely cashless? “Sure, in five to 10 years.”