Faced with a slowing economy, the Chinese government is this time looking to boost growth through tax cuts rather than stimulus spending

China’s economy seems to be slowing faster than the government would like, and US trade war tariffs are just one of the issues weighing down overall growth and threatening hopes for a choreographed and gradual deceleration. The last time this happened in 2008, Beijing responded with massive stimulus spending, thereby creating a debt mountain. This time, what should the economic planners do?

At the annual National People’s Congress in March, Premier Li Keqiang downgraded China’s 2019 gross domestic product (GDP) growth target to between 6.0 and 6.5%, warning of a “grave and more complicated environment.” At 6.6%, last year’s economic growth rate was already the lowest since 1990.

Instead of another strong stimulus to boost growth, this time Beijing is instead turning to “proactive fiscal policies” to encourage private-sector spending, with wide-ranging tax cuts, the largest overhaul of the individual income tax system seen in four decades, and tax breaks for a wide range of private companies.

“Fiscal room for the Chinese government has been pretty limited currently, if we look at the debt-to-GDP ratio, taking both official debt and contingent debt into account,” says Zhennan Li, China economist at Goldman Sachs. “This is one major reason for the government to take a finer approach to stimulate the economy this time.”

Though they may remedy some of China’s problems regarding growth, the tax cuts run the risk of resulting in even wider deficits. This would erode the government’s future ability to deal with the debt overhang and other pressing issues such as social security outlays.

China’s fiscal deficit-to-GDP target of 2.8% for 2019, up from 2.6% in 2018, is not large by global standards, but actual government spending has overshot the target every year since 2015. The country’s economic system also harbors additional hidden risks, the most obvious perhaps being the lack of diversification within key areas of the economy, and a top-loaded fiscal structure in which most revenues flow into central government coffers while most of the expenditures are shouldered by the local government.

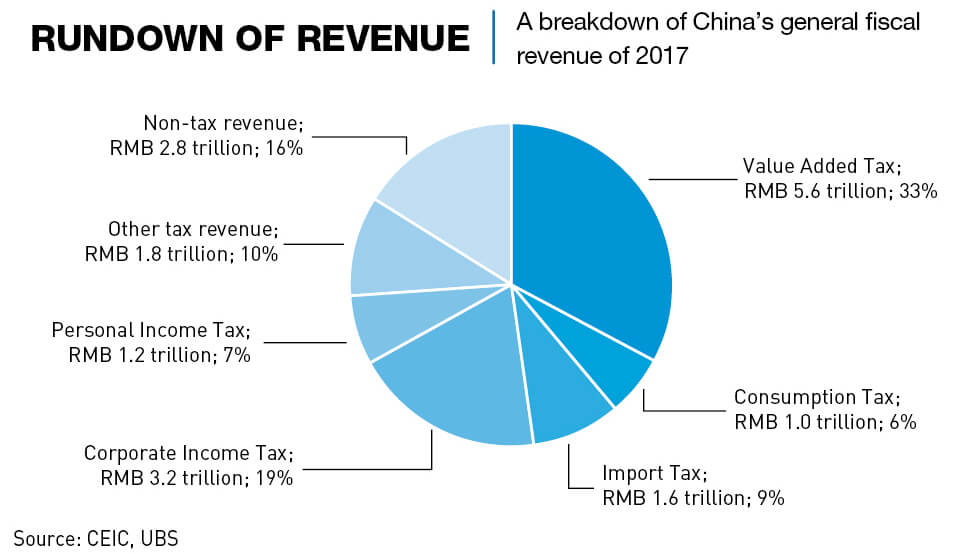

Still, government revenues increased by 6.2% last year, reaching RMB 18.3 trillion ($2.69 trillion), and China’s tax revenue as a percentage of GDP, often viewed as a yardstick for development, has increased steadily over the last two decades from 9.8% in 1995 to 20.1% in 2015. China is currently positioned below the OECD average of 34% and stands between other developed Asian economies such as Singapore (13%) and South Korea (27%).

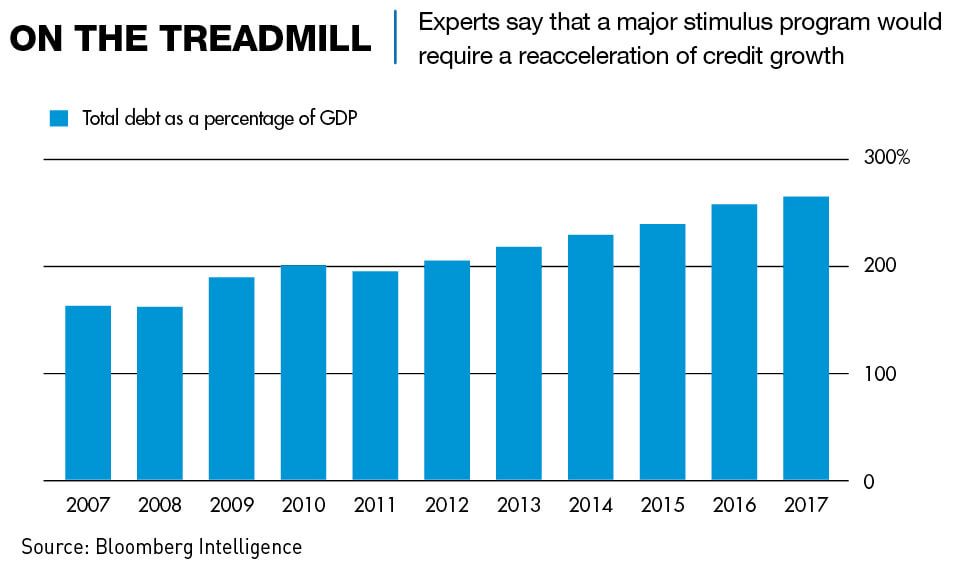

In 2008, during a national tax conference, then Vice Premier Li Keqiang told taxation officers to strictly enforce corporate income tax laws to boost revenues due to concerns at the time that taxation income might fail to match expenditures. In the decade since, China’s GDP growth has slowed to single digits, while the total debt load, mostly on local governments and state-owned enterprises, has increased to somewhere between 240-300% of GDP. This leaves little room for monetary stimulus. As a result, Li Keqiang, now Premier, is turning to fiscal levers instead, and the Chinese authorities are increasingly choosing changes to tax policy as a way to grease the wheels of economic growth. But critics fear that without structural reforms, tax cuts run the risk of providing only temporary relief.

The sources

China instituted sweeping changes to the Individual Income Tax (IIT) Law, which took effect from January 1 this year. They are aimed at reducing the tax burden for lower- and middle-income groups and thereby boosting private-sector spending. The law also revises the rules for foreign residents, reduces and streamlines tax categories, and introduces new tax reporting and anti-avoidance measures. More significantly, the law raises income thresholds and offers a string of new tax deductions for household welfare spending.

“To relieve burdens on low earners, the 3%, 10% and 20% brackets are widened, and the 25% bracket is narrowed,” says Melody Liu, tax manager at KPMG. “So relief is being directed at the bottom of the income distribution.”

The personal deduction threshold has been raised from RMB 3,500 ($513) to 5,000 per month, while new deductions cover expenditure on education, serious medical treatment, housing mortgage interest and rentals, and support for the elderly, said Liu. These complement existing exemptions for social security contributions, such as pension, medical and unemployment insurance, as well as housing fund contributions.

“The general policy behind it has been to try and alleviate the tax burden on the middle class,” says Paul Dwyer, director and head of international tax and transfer pricing at Dezan Shira & Associates. “It would certainly benefit those people that historically have not been earning a significant amount of money, in order to provide them with extra liquidity and more disposable income.”

By cutting taxes, however, the government is also giving up a large chunk of tax revenue. Income tax brought in RMB 1.39 trillion last year—around 7.6% of total tax revenue. This makes it the fourth largest source of tax revenue, after domestic VAT (with a 34% share), corporate income tax (19%) and value-added tax on imported goods and consumption tax (9%). Together, the four slices make up nearly 70% of the national tax pie.

In parallel with the IIT reform, new corporate tax laws are providing more flexible treatment for certain sectors and smaller-scale companies. In addition, the National People’s Congress in March unveiled further VAT cuts—with the standard rate dropping from 16% to 13%.

Overall, taxes, levies and fees will be slashed by nearly RMB 2 trillion, a figure which significantly beats the expectations of most analysts of RMB 1.3 trillion before the cuts were announced. The result has been the very clear signaling that the government has an even stronger commitment to tax cuts than first anticipated—and perhaps a greater necessity—to shore up the economy.

The mountain

The continuing slowdown in the growth of the economy is causing pain. Debt levels, meanwhile, look likely to rise again, after two years of decline. New loans jumped to RMB 3.23 trillion in January, well above estimates, and shadow financing increased for the first time in 11 months.

“The Chinese government has been pretty conservative with their official fiscal targets—always below or equal to 3%,” says Goldman Sachs economist Li. “So even with more tax cuts, they may have to cut back spending to meet their official fiscal deficit target.”

Beijing hopes to offset some of the impact of lower taxes by widening the tax base and plugging loopholes. New IIT anti-avoidance rules aim to tackle evasion and underreporting—which involves fighting offshore tax havens and artificial tax-motivated contracts.

At the same time, a broad institutional reshuffle last year transferred social security and corporate tax responsibilities from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security to the State Administration for Taxation, in an effort to improve tax collection. With stricter enforcement, China has also lowered social insurance premiums across the country—notoriously high by global standards.

“The expansion of tax brackets and new deductions should lower revenues, but at the same time the anti-avoidance rules might raise further revenue,” says Shanghai-based Lewis Lu, head of tax at KPMG China.

Exporters, small businesses and high-tech sectors—who constitute the backbone of the high-growth parts of the economy—will benefit from tax rebates and other advantages. New preferential corporate income tax rates of 5% and 10%—compared to the standard 25%—affect SMEs with annual profits of less than 1 million and 3 million RMB respectively and will last until 2021. The VAT exemption threshold for small enterprises has been increased to RMB 100,000 per month.

A crucial piece of China’s taxation puzzle long term is property tax, which basically does not exist in China today. The government trialed individual property tax in Shanghai and Chongqing in 2011, but had to abandon the effort due to massive opposition from property owners, which risked a sharp fall in property prices. Local governments across China currently depend heavily on land sales and property translations to fund local utilities and infrastructure, and a key target for the government is shifting to a property tax arrangement, providing stable income for local governments.

The central government hinted at the National People’s Congress session in March this year that another effort would be made to implement property taxes, but psychologically it is hard for Chinese owners to accept for a number of reasons, one being that they don’t actually own the leasehold of their apartments and other properties—all property in China is leasehold from the state, typically for 70 years.

The official goal is to insert the thin edge of a tax wedge into the situation. Ying Zhongqing, deputy director of the financial and economic affairs committee at the National People’s Congress, said that if the central government implements a property tax, it would, as with income tax, have a minimum tax-free threshold to protect the interests of average home owners.

“Whoever has a larger house will pay more taxes, and whoever lives in the major cities, or in central areas in a city will pay more taxes,” Ying told the 21st Century Business Herald, adding that the tax-free threshold could be set at 40 to 60 square meters per person.

For now, provinces and municipalities across China have instead announced reductions of up to 50% in local taxes, including resource tax, stamp duty, and urban land use tax for small enterprises—an estimated total fee reduction of RMB 200 billion, according to Lu.

A thousand cuts

Stimulus measures are not being actively implemented, but some analysts believe tax cuts alone may not be enough to spur growth.

“During cyclical weakness as we are seeing now for the Chinese economy, impacts of tax cuts could be pretty limited, as firms may not have a strong incentive to increase investment, even with improvement in profitability, and households may not have a strong motive to spend more even with increases in disposable income,” says Goldman Sach’s Li.

Michelle Lam, Greater China economist at Société Générale, estimates that the impact of the RMB 2 trillion tax cuts will be an improvement in GDP growth in the range of 0.7 to 0.8%. “However, a caveat is that the government is likely to cut spending to balance the books, so the ultimate impact may not be as big.”

A key focus of the tax reforms is to correct some of China’s dire wealth inequalities — a potential future stress test for the government. However, KPMG’s Lu points out that as China’s income tax revenue accounts for only 7% of its total tax revenue, taxation plays only a limited role in adjusting income distribution. In addition, without proper implementation of inheritance tax, the new reforms may have a limited impact on wealth distribution.

Still, the increases in disposable incomes and new welfare deductions could potentially lift living standards and life quality for lower income earners across the country.

Catch-22

The key winners of the tax reforms are actually exporters, high-tech manufactures, small, medium and micro-sized enterprises—along with the venture capital firms that fund high-tech startups. At the same time, the central government says it will increase transfers of payments to local authorities, making up for the revenue gaps caused by reduced tax income at the local level. State-owned enterprises (SOEs), on the other hand, appear to have drawn the short straw, as private sector tax reductions will in effect be funded by state-sector profits.

Unfortunately for the authorities, the contradiction between maintaining growth and controlling debt is unlikely to go away. Increased investment spending would require a re-acceleration of debt growth, and tax cuts will inevitably increase the public deficit and further add to debt in the long run. Still, fiscal policy steps are seen as experts as the best option for short-term growth.

“We think corporate tax cuts are the preferred tool for China at the moment,” says Lam. “Infrastructure investment is the quickest way to stimulate the economy, but it is not the most efficient way to make use of resources and it could add on the debt burden of local government and financial vehicles, with the latter under the government’s pressure to deleverage. In contrast, tax cuts work more slowly to reflate the economy, but the savings return to the private sector who can make investment decisions based on risks and returns—this encourages a more efficient allocation of capital.”

“If the growth rate of fiscal revenue is not far away from GDP growth, the government will face no pressure for further cuts, because local government can also issue bond or leverage by the local government financing vehicles,” says Yue Su, China Economist at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). “However, there’s a risk that local government has been leveraged too much in the off-balance-sheet. If this ratio is moving up quickly, then it might leave limit room for further tax cuts.”

However, Li argues that the government has notably strengthened fiscal discipline as well as improved the balance sheets regarding government borrowing. “Overall, we think these underlying changes can make the debt costs of stimulus smaller,” he says.

The new tax policies have the added benefits of helping to streamline tax collection, incentivizing tax reporting and possibly contributing to some extent to a fairer wealth distribution. Tax breaks for startups, SMEs and high-tech ventures could spur growth and private entrepreneurship without sacrificing long-term sustainability.

Nevertheless, sooner or later, a wide range of experts say, China likely has to consider larger structural reforms—with a redesign of fiscal relations between central and local governments, a deepening of supply-side reform, improved support for SMEs and possibly addressing issues such as the inequality of power between state and private capital.

“Reducing financing cost for private enterprises cannot be done overnight, because banks are concerned about the non-performing loan ratio,” Su says. “Tax cuts are the measure that the government can do in the short term.”