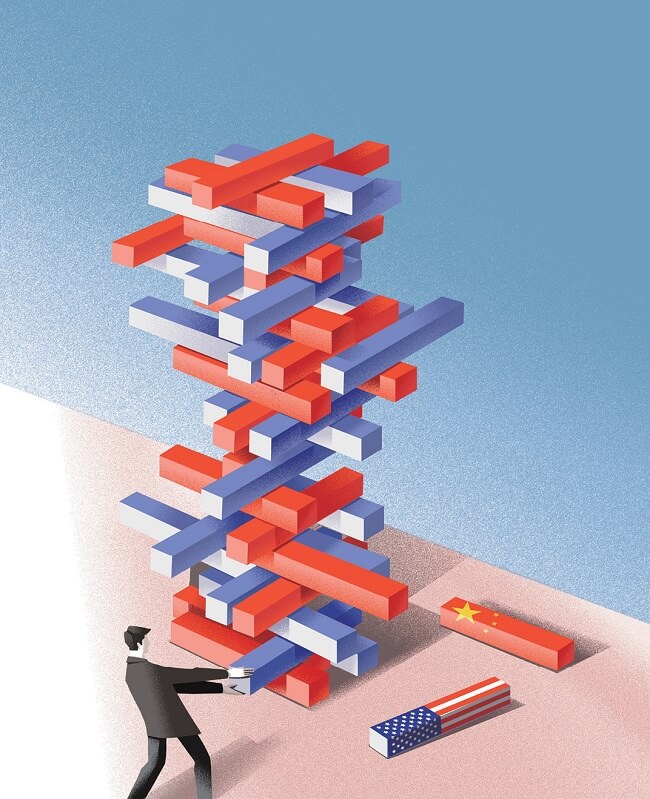

The US and China are playing a risky game as they try to reset their economic relationship. Negotiations are underway, but any deal may only mark the start of a new era of heightened tensions in the world’s most important economic relationship.

The US and China are playing a risky game as they try to reset their economic relationship. Negotiations are underway, but any deal may only mark the start of a new era of heightened tensions in the world’s most important economic relationship.

As Donald Trump signed the memorandum proposing the introduction of tariffs on $50 billion of Chinese imports on March 22, the president of the United States quipped: “This is the first of many.”

The moment marked a dramatic escalation of tensions with China over trade, which have since risen even higher with China’s threat of a tit-for-tat response and Trump’s announcement that the US may consider an extra $100 billion worth of tariffs.

But for many observers, the signing of the memo also represented a deeper shift in the dynamics of the world’s most important economic relationship.

In his Sinocism newsletter two days later, veteran US-China analyst Bill Bishop framed the Trump administration’s move in historic terms: “The Trump administration… has now signaled officially that engagement is dead and we are in a ‘New Era of US-China Relations,’ in which there will be intensified competition if not outright conflict,” he wrote.

This change in attitude could have implications far beyond even the prospect of a possible trade war. For decades, economic engagement has been the underlying foundation of the US’s China policy. The doctrine holds that the more China is integrated into the global economy, the more it will open its markets and align policies with those of its liberal capitalist partners. It was the engagement doctrine that led to China being allowed to join the World Trade Organization in 2001 based on assurances of changes.

Many in the US and elsewhere have long criticized China for having changed too little to meet international norms on trade, investment and economic policy, and there are clear signs that the US policy elite is now moving to the view that the policy of engagement has not worked. In January, a White House report called China’s WTO accession a mistake. The next month, the president branded China a rival that “challenge[s] our interests, our economy and our values” in his 2017 State of the Union address.

“China’s integration into the global trading system hinged on its willingness to reciprocate on tariffs, but few people expected it to hold on to such extensive non-tariff barriers to trade and investment,” Mark Williams, Chief Asia Economist at Capital Economics, tells CKGSB Knowledge. “Western governments have been lobbying unsuccessfully for China to open up its markets to Western firms for years.”

Some US policymakers have concluded that power politics is the only way to convince China to implement the reforms they desire. “There are people in Washington who believe they can tighten the screws on China, and that China will bend to their will,” says Williams.

It is this belief that seems to be behind the Trump administration’s moves to place increasing restrictions on China’s imports. “There is a grander strategy behind it,” says Louis Kuijs, Head of Asia Economics at Oxford Economics. “There is a stance within the Trump administration: we need to be more forceful.”

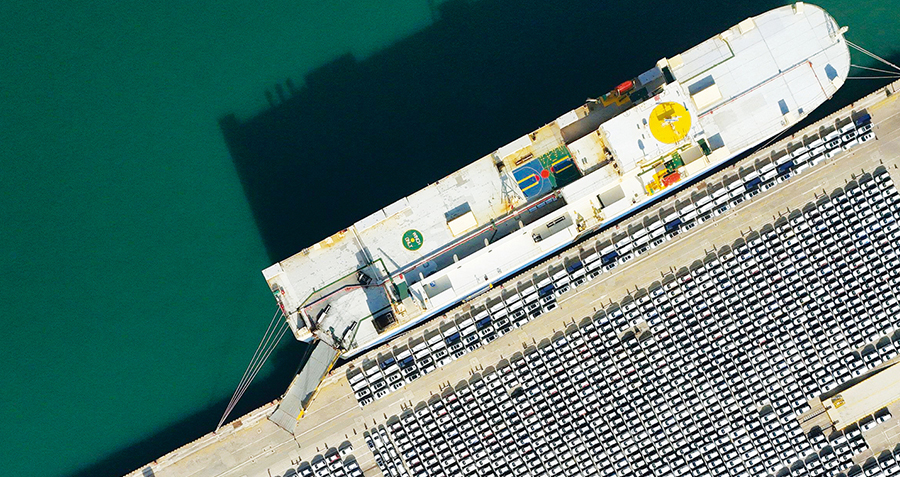

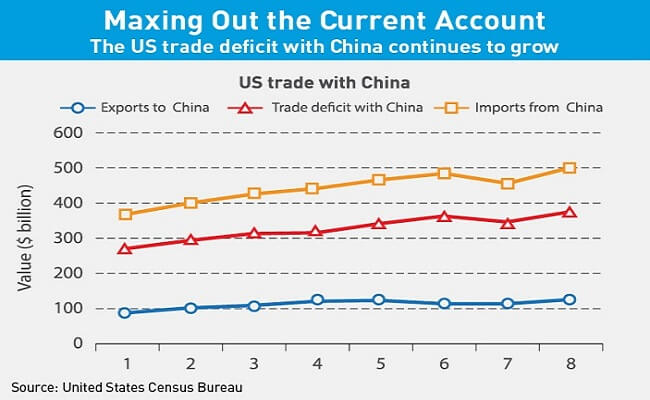

The administration appears to be using the threat of a trade war to force the Chinese government to meet two specific demands. The first is a reduction in the bilateral trade deficit with China, which rose to $375 billion in 2017, according to US government data.

“I’ve been speaking with the highest Chinese representatives, including the president, and I’ve asked them to reduce the trade deficit immediately by $100 billion,” President Trump said after signing the memo on March 22.

The second demand is that China accelerates its market reforms by opening more industries to foreign competition, reducing import tariffs and abandoning rules that force multinationals operating in China to form joint ventures and transfer technology to local partners. Trump also alluded to this issue in his statement:

“The word that I want to use is reciprocal,” he said. “When they charge 25% for a car to go in and we charge 2% for their car to come into the United States, that’s not good.”

China’s response so far has been measured with President Xi Jinping’s government keen not to escalate tensions. Some within the government remain confident that the president will eventually settle for a deal. “When two parties negotiate you have to bluff and Trump is a businessman,” one adviser told the Financial Times in late-March.

But the hawkish turn in the US is undoubtedly steering US-China relations in a treacherous new direction. In the short term, there is a danger that the US will make demands that China is unwilling—or simply unable—to meet. And even if the two sides cut a deal in the coming weeks, it may only be a matter of time before the same issues cause tensions to rise once again.

Deflating the Deficit

One potential stumbling block is the US’s trade deficit with China. Opinion is divided over how serious the demand for a $100 billion cut in the bilateral deficit really is. Some believe—and, given the “bluffing” comment, this may include people within the Chinese government—that the figure is merely a bargaining chip that may be traded in favor of more market opening from China.

But others are less certain. One analyst shares that a source close to the Trump administration calls the president deadly serious about reducing the trade deficit. “Trump really is a mercantilist kind of guy,” he says. “He’s a real hardliner when it comes to the current account.”

Peter Navarro, Director of the White House National Trade Council, has called the US trade deficit a potential national security threat. If the president does see the bilateral trade balance in those terms, this has the potential to create an impasse in negotiations, since analysts almost universally predict that China’s surplus with the US will expand even further in 2018 unless dramatic reforms are introduced. Ironically, the reason for this is the strength of the US economy and the Trump administration’s tax-cutting agenda.

“Now that the US economy is warming up, we’re seeing the hunger for imports is rising,” says Kuijs. “In 2018, we’re going to have further acceleration in domestic demand in the US because of the fiscal plans and the tax cut.”

When it was passed in December, there were widespread fears in China that the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—which reduced the US corporate tax rate to 21%— would trigger an exodus of capital and manufacturers across the Pacific.

Maximilian Kaernfelt, a researcher at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, believes that US officials may have been hoping for the same. “I’m not saying that these tax cuts were specifically targeted at China, but I find it hard to believe that in the meeting no one said ‘China’ at one point,” he says.

However, thanks partially to a one-off tax break for foreign businesses handed out by the Chinese government, that outflow appears unlikely to materialize, according to Shaun Rein, Managing Director of the China Market Research (CMR) Group.

“If companies think that there are still opportunities in China, they’re going to keep that money here and grow,” says Rein. “They’re not going to go back to the US.”

Instead, the US tax cuts look more likely simply to stimulate consumption, and therefore demand for imports.

Destined for Trade War?

So far, the US’s approach to reducing the deficit has focused on slapping tariffs on Chinese imports, with $6 billion worth of goods already affected by new duties since the start of the year and a further $150 billion under consideration. But this approach is likely to prove painful in the short term and ineffective in the long term.

Even the proposed $150 billion worth of tariffs may not reduce the US’s bilateral trade deficit by the stated target of $100 billion. In 2017, for example, the US’s trade deficit with China rose over $30 billion year-on-year.

What’s more, the real impact of the tariffs would be much smaller. For one thing, the tariffs will first go through a weeks-long consultation period where US industries will lobby intensely for them to be watered down or scrapped. “This means the tariffs are unlikely to be as heavy-handed as they might have been,” Williams concluded in a note in late-March.

There are also other reasons to expect the impact to be relatively weak, according to Williams. “In many sectors there are few alternative suppliers that US buyers could switch to,” he added. “Consumers may also not be deterred much by the resulting price rises.”

Slapping tariffs on imports from China will also do nothing to solve the underlying causes of the US trade deficit. This means that any reduction of the US bilateral deficit with China is likely only to lead to an increase in the deficit with other countries, according to Kuijs.

“If you don’t tackle a macroeconomic problem with macroeconomic instruments, then you’ll see all kinds of second-round effects and evasions,” he says. “There’s a lot of that going on: Chinese companies setting up production in Malaysia or Vietnam, for example.”

In reality, the tariffs announcements are likely intended to serve as a warning to China that the US was serious about renegotiating the bilateral relationship, rather than as a genuine solution to the trade deficit.

US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin hinted strongly at this during a Fox News interview in late-March. “If they open up their markets, it is an enormous opportunity for US companies,” said Mnuchin. “I am cautiously hopeful we can reach an agreement, but if not, we are proceeding with these tariffs.”

Some believe that the US may have miscalculated the potential risks and rewards for the Chinese government of bowing to this threat. On the one hand, the tariffs give the US less leverage than some may think. Capital Economics calculates that the impact of the $50 billion round of tariffs on China’s gross domestic product (GDP) would be only 0.1%, while the extra $100 billion of duties may raise this to 0.5% of GDP. This figure is “no longer a mere rounding error,” according to Williams, but would hardly bring the Chinese economy to its knees.

On the other, China’s leaders are under pressure not to be seen to cave in to US demands. “I think the two sides are a long way apart in terms of their perception of the US’s ability to coerce China into changing its policies,” says Williams. “In Beijing, the chances of that happening in any significant way are pretty close to zero.”

When the Chinese government announced new duties on just $3 billion of US imported goods in late-March, Beijing received criticism on social media for its lack of action. Even Lou Jiwei, a former Chinese finance minister, pronounced the measure “relatively weak.” It was in this context that China announced a potential tit-for-tat $50 billion round of tariffs on American imports a week later.

If the US tries to strong-arm China into making potentially humiliating concessions, China’s leaders may feel they have no choice but to call the bluff, Williams calculates. “There’s a risk of the two sides running into each other because neither is willing to swerve out of the way,” he says.

Saving Face

The easiest way to step back from the brink of a trade war would be for US and Chinese officials to agree a compromise deal, allowing both sides to claim victory to their respective domestic audiences. According to Stanley Chao, Managing Director of All In Consulting and author of Selling to China, this remains the most probable outcome.

“It’s all posturing on both the US and China sides. China has too many social-economic issues to worry about: pollution, transportation, food quality, medical services,” says Chao. “Eventually, both parties will meet and resolve the matter.”

CMR’s Rein believes that China will offer the US some concessions on market access to secure a truce. “In the end calmer, rational minds will prevail,” he says. “There will be more opening, for sure, in financial services. I expect that there will be more opening in autos too.”

According to The Wall Street Journal, relaxing restrictions on foreign firms and imports in the finance and auto industries was among the list of demands sent by White House officials to Chinese Vice President Liu He in a letter late-March. The list also included a request that China buy more US-made semiconductors in a bid to reduce the trade deficit.

There is a chance that China may agree to some of these asks because the government has been planning more opening in finance and autos for several years, according to Rein. “I think China will bow down and do it,” he says. “It’s not going to have a meaningful impact on the economy.”

The question is whether the US would be satisfied with such a relatively limited deal, which would likely not get close to reducing the bilateral trade deficit by the stated target of $100 billion. China’s total imports of US motor vehicles in 2017, for example, were just $10.6 billion, according to US government data.

As Williams points out, China would struggle to reduce the deficit through selective imports of American goods: “Soybeans are one of the major Chinese imports from the US. China’s purchases account for a large share of the US crop. But they still amount to only $12 billion.”

Neither will any deal include concessions from China in areas that it deems strategically important, Rein predicts. “The big issue is the internet and high-tech companies,” he says. “You’re not going to see opening there. But if you did, that’s where you’d see a meaningful impact positively for American business.”

The same applies for the Chinese government’s practice of requiring multinationals operating in China to form joint ventures and share their intellectual property with local companies, a source of resentment among US firms, Williams forecasts.

“Those efforts are seen in Beijing as a key element of efforts to shift China’s economy to high income status,” Williams wrote in a March note. “Industrial upgrading is the core of the Made in China 2025 program, which President Xi has put at the heart of his agenda.”

If the Trump administration’s aims are mainly political, it may choose to ignore these realities for now. But the issues will not go away.

Strategic Competitors

Even if the US decides to abandon its tactic of threatening a trade war to force China to open its markets, the “post-engagement” era of US policy toward China could be here to stay.

“There has been growing disillusionment with the results of economic engagement with China that goes well beyond the White House,” says Williams. “There is now a growing consensus even in the business community, which has traditionally been a cheerleader for opening up to China, that this should not continue.”

Ann Lee, author of What the US Can Learn from China, agrees that both Republicans and Democrats are now in favor of taking a tougher line with China. “I think that this has been building over the years,” she says. “Trump merely gave voice to sentiments that were already there.”

Even Senator Elizabeth Warren, one of Trump’s fiercest critics, appears to agree with aspects of the president’s tough approach:

“The whole policy [toward China] was misdirected,” Warren told reporters during a trip to Beijing in April. “Now US policymakers are starting to look more aggressively at pushing China to open up the markets.”

There is a new consensus forming in Washington, Williams says: “If China won’t open up its markets, then Chinese firms should face more restrictions on their ability to invest in the US and Europe.”

The US has become stricter in its oversight of proposed Chinese takeovers of American companies since the start of the year. It has blocked a string of deals, including the bid of Ant Financial, an Alibaba affiliate, to acquire MoneyGram and the buyout of semiconductor firm Xcerra by Chinese state-backed fund Hubei Xinyan.

A bill expanding the powers of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), a government office that scrutinizes foreign acquisitions, is making its way through the US Congress. It has broad bipartisan support, according to The Economist.

If China does not change its strategic investment practices, the US may have no choice but to introduce extra protections. “Is China playing by the rules? Is China’s economic system even compatible with our global system?” asks Kuijs from Oxford Economics. “I think these are legitimate questions to ask.”

But there are also signs of a harder edge to the US’s restrictions on investment, which has less to do with reciprocity and more to do with maintaining US dominance. In December, the US government branded China a “strategic competitor” for the first time in its annual national security strategy review, introducing a zero-sum element into US economic policymaking.

“These are things that if China dominates the world, it’s bad for America,” US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer told a Senate committee in March.

The Treasury Department is currently working on a plan that would go far beyond the current restrictions, according to Bloomberg. It would use an obscure 1977 bill granting the president emergency powers in the event of an “unusual or extraordinary threat” to introduce a blanket ban on Chinese investment in certain strategic industries, such as 5G wireless networks and semiconductors.

“It has nothing to do with an even playing field; it has nothing to do with playing fair,” comments Lee. “It has everything to do with the US wanting to be number one.”

For China, the restrictions on investment could prove more damaging in the long run than a trade war, especially if the European Union also closed off its market. Acquiring foreign technology and know-how is crucial to China’s efforts to upgrade its manufacturing sector—which currently powers 31% of the country’s GDP—before it completely loses its cost advantages over developed economies.

Worryingly for China, sentiment also appears to be shifting in Europe. “Let me say once and for all, we are not naive free traders,” said Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, in his State of the Union speech last September. “Europe must always defend its strategic interests.”