Physical retail in China, malls especially, is facing huge challenges from without and within. E-commerce offers value and convenience, and old stores were poorly built. The future requires a reimagining of what shopping can be

At the enormous Pacific Department Store on Shanghai’s Huaihai Road, barriers block the street entrances and windows are shuttered. The store, one of the largest on one of the city’s busiest shopping streets for nearly two decades closed in January, leaving a “Bye Bye Sale” banner still hanging above the entrance pillars. The shell of the store now sits incongruously opposite the K11 mall, which has been thriving ever since implementing a smart re-think of the shopping mall concept a couple of years ago.

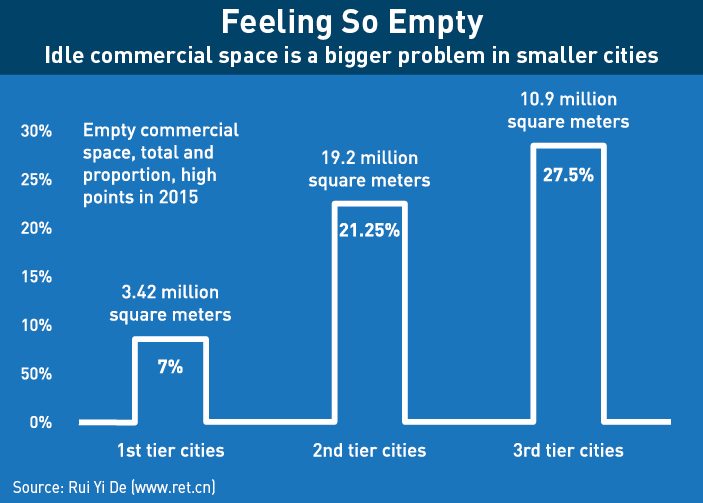

The lesson of the different fates of these two shopping centers is clear—adapt or die. Retail is not declining in China, it’s just changing. The growth of the country’s consumer market has continued at an incredible rate in recent years, with retail sales up almost 10% in 2016, hitting $4.84 trillion. But the disintegration of the physical store market has been just as stunning, with a growing number of empty store fronts in every city in China.

The rise of e-commerce has hit retail sales hard, but an explosion of malls over the past decade is also a big part of the problem, giving China a glut of often poorly considered space.

“Many of these new retail projects were launched without proper research on the fundamentals: footfalls, occupier demand, shopping patterns and competition,” says Harry Tan, Head of Research, Asia Pacific at TH Real Estate.

Gloomy forecasters warn of further physical shopping misery—a September 2016 report from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences predicted that one-third of all shopping centers in China could be shuttered in the next five years, while at the World Retail Congress in April 2016, held in Dubai, China Chain Store & Franchise Association Secretary General Dr. Pei Ling said the Chinese domestic retail industry is experiencing the “toughest period in its 30-year history.”

Under/Over

The emergence of China’s consumer retail sector in the past three decades has mirrored the country’s rise to economic powerhouse status. Driven by what was originally a huge shortage of retail space and the assumption that a growing middle class would create enormous demand, developers began churning out chain stores and Western-style malls at an unprecedented rate.

The shift appears to have left developers nonplussed. In 2015, 60% of the world’s shopping malls under construction were in China, according to US-based commercial real estate services agency CBRE, with 4.1 million square meters in Shanghai, 3.4 million square meters in Shenzhen and 3 million square meters in Chengdu, the top three cities on the global list. To put those figures in some visual context, Shanghai alone was building the equivalent of about 16 Empire State Buildings that year.

China today holds nine spots among the top ten most active cities for shopping centre construction globally, with some experts predicting that as many as 7,000 new malls will open in China by 2025. Vice-President of property developer Wanda Group, Wang Zhibin, at RREM 2016, a Chinese real estate industry conference, outlined plans to open 60 new Wanda malls on top of their existing 133 locations.

There are some good reasons for wanting to expand retail locations—building the retail sector in China is essential as the government shifts away from manufacturing as the economic core, and not all consumer purchases fit the online model. But there has been an issue with quality, which has not always been world-class.

“Over the past decade, an unprecedented amount of retail development has taken place in China,” says Tan of TH Real Estate. “Due to over-developments during this period, a significant portion of malls have been hastily built by developers whose previous experience was in residential developments, where the strategy is to pre-sell in order to generate quick cash flow, in order to fund future developments.”

But in the end, the customers just were not there. This dislocation between supply and demand was partly due to local governments, which pushed developers to build malls to boost tax and land incomes, as well as local employment.

“There wasn’t any fundamental knowledge or experience about what it took to build a successful shopping mall,” says Melanie Alshab, Managing Director at Kensington Asset Management. “It was part of a ‘Build It and They Will Come’ mindset.”

Indeed, a 2015 study from Jones Lang LaSalle, a commercial real estate services and investment firm, concluded that only 10-15% of China’s shopping malls were “international-grade,” meaning a lot of sub-standard malls.

Worst Netmare

Exacerbating this problem of oversupply is the continued rise of an already gargantuan e-commerce sector. The internet first came to China permanently in 1994, and e-commerce giant Alibaba was founded in 1999, when internet penetration was still in the low single digits. By 2015, internet penetration had topped 50% and Alibaba had exploded into a multi-billion dollar company.

This enthusiastic adoption of online retail has caused trouble for developers. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, online sales boomed in 2016, surging 26.2% on the year before to reach RMB 5.16 trillion ($751 billion), around 15.5% of total retail sales, online and offline.

In comparison to physical retail, e-commerce in China is convenient, competitively priced and well-organized. This is particularly true in remote areas, and the latest retail data from the government shows stronger growth in rural areas than urban ones. And with hundreds of millions of smartphone users in China, mobile sales are also soaring. Market research firm eMarketer predicted that in 2016 mobile would make up half of all online sales (final numbers have yet to be tallied), and that by 2019, mobile consumers will spend $1.5 trillion annually, a quarter of all retail sales.

“E-commerce is probably the single biggest force exerting pressure on traditional shopping malls,” says Steven McCord, Head of Retail Research for Asia at Jones Lang LaSalle. “Online retail accounts for most of the growth in China’s retail sales, eroding growth that previously might have gone to malls. Its effects are most keenly felt in sectors like fashion that once were shopping malls’ traditional bread and butter tenants.”

Unsurprisingly this has spelled trouble for most malls (although not all). Combined with the oversupply of retail space, much of it poor quality, the industry is facing a sizeable structural problem. Retailers and department store operators have already begun closing shops. Malaysia-based Parkson, which operates more than 70 department stores in China, closed several stores last year following a 58% drop in China net profit. Lifestyle International, which operates the Jiuguang upmarket department stores, closed its Shenyang store in December, two years after it opened. New World Department Store China warned in its 2016 financial report that it was getting tougher to compete with online shopping amid a massive supply of shopping malls.

Malls are not the only retail class struggling in the face of e-commerce. British retailer Marks & Spencer announced recently it would soon close all its ten stores in China, although it will keep an online presence in the market. And China’s online grocery market is predicted to grow nearly five times its current value of $41 billion by 2020, a sign of trouble for physical grocery retailers. Carrefour has closed nearly 30 stores in China in the last three years, planning instead to expand its Carrefour Easy convenience store range, which also offers pick-up for online shopping. Walmart has also hit its share of troubles, saying in 2015 it was closing some China stores in under-performing areas while opening another 115 and expanding its online offerings.

Reboot

But as many retailers struggle, there are also investors looking to buy existing developments in good locations and perform turnarounds. A fund run by Gaw Capital acquired Beijing’s Pacific Century Place mall for $928 million in 2014—previously a struggling department store. The new project was repurposed to target Beijing’s more discerning consumers, with “mini blocks” of retail and increased dining space. The transaction landed Gaw the Asia Deal of the Year Award from PERE, Private Equity Real Estate news, an industry publication.

“We have seen repositioning of many under-performing malls over the years,” says Tan. “For instance in Beijing’s Zhongguanchun district, the ‘Silicon Valley of China,’ many malls that once sold electronic devices are now housing startup technology firms and incubators. This trend is likely to persist, and going forward we should expect to see a significant number of de-centralized malls being repurposed or redeveloped.”

Operators are also repositioning malls from being merely shopping destinations to entertainment complexes. Malls in China are leasing as much as half of their space to restaurants, cinemas, language schools, medical centers, theme parks, museums, spas and more. Shopping spaces with a specific niche attractive to the new middle class are also doing well, which is why K11 is thriving just next to the failed Pacific Department Store. The complex hosts big-name art exhibitions including Monet and Dali, in-mall experiences such as the K11 Garden, plus design-focused stores and newer brands.

“Given that product purchases can now be made with a few clicks on a smartphone, shopping malls need to evolve from being mere collections of stores and products to become lifestyle destinations,” says Jason Leow, CEO of CapitaLand Mall Asia, which has 56 malls in China, and ten more in development. “To cater to these trends, our malls are becoming one-stop lifestyle destinations that offer ‘retailtainment,’ which includes experiential retailing, food and beverage, and leisure and entertainment options.”

More mall operators are also integrating loyalty schemes to both reward customers and build their own customer database. CapitaStar, CapitaLand’s loyalty service lets shoppers reserve car parking spaces, locate shops and promotions within the mall, earn reward points, and queue digitally at restaurants.

“CapitaStar provides us with an expanding database of shoppers’ habits and tastes through information collected from spending at our malls,” says Leow. “This information helps us enhance the customer experience.”

Integrating physical and digital is becoming increasingly common at well-operated shopping centres. The two Shanghai shopping malls of Hong Kong property developer Sun Hung Kai Properties use iBeacon, a protocol developed by Apple, to identify the exact location of shoppers within a store and send relevant messages and offers through their smartphones. Touch-screen platforms, e-signage and video walls are common in newer generations of malls, along with free Wifi, enabling stores and mall operators to collect and analyze data about their customers.

Let’s Get Physical

As the shake-up in the industry continues, e-commerce operators have also been moving into physical retail, further blurring the lines between online and offline shopping. Online giant Alibaba has led the charge. In January, Alibaba announced it was taking a stake of 74% in department store operator Intime Retail, which operates 29 department stores and 17 shopping malls in China. Alibaba also has a stake in Chinese retailer Suning.

Other e-commerce giants are moving to compete with Alibaba’s O2O efforts, with varying degrees of success. A 2014 much-publicized $3 billion joint venture to “revolutionize mall shopping” between online giants Baidu and Tencent, with property company Wanda Group, fell apart after Baidu and Tencent backed out quietly last year. At the time, they imagined the world’s largest e-commerce platform, helping shoppers to find products in malls and retailers to better manage their payments and data.

While still in experimental stages, industry experts agree that the integration of online and offline must be the way retail develops. Even the government is in favor of integrating the two, with China’s State Council issuing a note in November 2016 to encourage the transformation of retail supported by data technology, calling for more innovation and cross-discipline integration.

However, even though some developments can be repositioned as modern, digital-focused malls, many cannot.

“In China, they often build in concrete, they don’t use steel, and one of the things about a shopping mall is that it has to change in order to stay relevant and interesting,” says Alshab. “When looking at second- and third-generation malls, even before you talk about any new technology, you really need to go back to the basics and look at the way they are built. These first generation shopping malls, which are now looking at attracting new tenants, new types of entertainment clients, they physically can’t change their space and it’s very difficult. In these cases, the only option is often to knock them down and rebuild.”

The style of financing retail development in China has also created problems with flexibility. Selling an individual store or floor—known as strata-titling—was popular where developers needed a quick return on capital, but renders a mall-wide regeneration almost impossible.

“In cases where wholly owned malls in tier one cities have persisted as under-performing assets, we have seen some of these properties sold off. Investors have been interested in the properties with high conversion or upgrade potential,” says McCord. “But closures are most common in retail properties that aren’t wholly owned and are instead strata-titled. Strata-titled malls tend to be lower-end, and it has been difficult for them to mount coordinated efforts to adapt themselves to new shopping trends. Most of China’s so-called ‘ghost malls’ emerged from this sector.”

Concrete Psychological Value

But regardless of any and all challenges, there is an enduring need for retail spaces. The presence of stores is very important in brand-building—especially for high-end brands, many of which find their stores serving almost as showrooms to a mobile consumer that eventually buys outside China, where they can avoid eye-wateringly high import taxes. Brands such as jewelry boutique Tiffany says Chinese consumers are their biggest purchasing group, even though China is not their biggest geographical presence.

US technology giant Apple has recognized this trend, and created popular stores where shoppers go to browse, play, touch and see the goods, without facing pressure to buy on the spot. And China is still where brands often want to open their first Asian store. Children’s department store Hamleys opened its debut China store in October, while UK department store House of Fraser opened its inaugural store in December. Adidas has plans for 3,000 new stores in China by 2020, and coffee giant Starbucks says it will open 500 new stores annually for the next five years.

Lingerie chain Victoria’s Secret made its first foray into China last year, and opened a new flagship store this year on Huaihai Road, just a stone’s throw away from the shuttered Pacific Department Store. The new lingerie store will replace a now-closed Louis Vuitton boutique, perhaps representing the shift away from large luxury product houses.

With demand ongoing for the right type of retail, developers in China are gradually adapting to build higher quality malls and take a longer-term role as retail landlord.

“Shopping mall developers and operators have had to step up their game to survive in a more crowded, more competitive marketplace,” says McCord. “Several years ago it was possible for some local developers to get away building second-rate copies of a Wanda Plaza, but now they need to build to at least to Wanda’s standard while also finding ways to distinguish their environments and shopping experiences from all the other malls going up at the same time.”

Retail in China is going through a process of maturing and changing, but it is far from obsolete. Instead, physical retail in China is growing up. Consumers still want an attractive and pleasant physical space where they can interact and socialize, and a new generation of malls that mixes retail and entertainment fits their demands well. Enthusiastic consumers want to try the latest restaurants and browse in the stores of exciting, fresh new brands, and they have disposable income to spend. But e-commerce and mobile shopping is only going to grow, and the future of China’s physical retail sector is certain to be with those mall operators who work with, rather than against, digital shopping.

“Physical retail remains an important part of a shopper’s journey, complemented by digital channels that augment the buying experience,” concludes CapitaLand’s Leow. “Retailers now recognize that omni-channel is the way to go.”