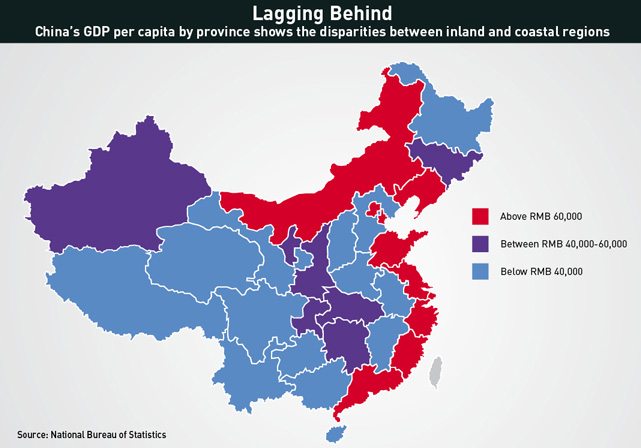

There are stark regional disparities between the inland and the coastal regions in China. Can the less-developed regions ever catch up with the coast?

It is a hot summer morning when Mr Chen and his family arrive at the Bund—and hazy to boot. Hailing from the inland prefecture of Chongqing, Chen moved out to the coast to follow his boss, who had found business opportunities near Shanghai in the neighboring prosperous province of Jiangsu. But today as barges putter by below the iconic skyline of Lujiazui, Chen says, “We’re here for fun.”

Like many before—and no doubt after—Chen was drawn from his inland hometown to the prosperous eastern corridor by the lure of greater economic opportunities. The numbers are on his side: the chief beneficiaries of China’s three-decade economic boom have been the provinces on China’s southern and eastern coasts, with booming metropolises such as Guangzhou and Shanghai acting as advertisements within China for all that is modern and new.

But these gleaming coastal skylines obscure lagging development inland. There, provincial economies reliant on cheap labor and low-value-added manufacturing are being left behind as China’s east transitions toward an e-commerce and services-centric model.

Today more than ever, Deng Xiaoping’s decision to let some get rich first begs the question of whether the rest ever will. Programs targeting inequality through spending on infrastructure and other development initiatives have helped boost GDP in China’s west, center and northeast, but the long-hoped-for trickling down of wealth from such government spending has yet to emerge.

“Build roads if you like,” says Jane Golley, Associate Director of Australian National University’s Centre on China in the World, whose research focuses on regional development. “But if there’s no market at the end of it… it can be very wasteful.”

State of Nurture

While market mechanisms may have spurred inequality, neither Mao nor Deng began with a blank slate. The now-thriving cities of Shanghai, Fuzhou, Guangzhou, Ningbo, Xiamen, Tianjin and Hong Kong first became littoral leaders of industry following the Opium Wars, when they became treaty ports after the Qing Dynasty’s defeat by the British Empire.

These cities’ coastal locations and commercial infrastructure made them ideal hubs for international trade, but after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 these strengths became problems. Mao Zedong condemned the concentration of virtually all economic capacity on the eastern seaboard as “irrational” in light of the inland provinces’ lagging development.

Mao’s development strategy for the interior was bolstered by geopolitical developments when China’s ties to the Soviet Union became strained, and calls to establish a “Third Front” to fall back to inland should invasion occur helped direct state spending to industrial development away from the coast. Though short of Mao’s goal of moving 90% of heavy industry inland, the interior’s share of industrial output eventually rose from 31% in 1953 to 46% in 1978, according to Golley’s research.

Market Nature

After Mao died in 1976 and Deng Xiaoping assumed leadership of China, the Chairman’s inland-focused development plans were quick to go.

“The high cost imposed by the inefficient relocation of industry to remote, underdeveloped areas was one of the many problems that called for dramatic changes to China’s economic system,” Golley says. Ever the pragmatist, Deng argued that “since conditions for the country as a whole are not ripe, we can have some areas become rich first. Egalitarianism will not work.”

Deng kicked off coastal development by announcing the Open Door Policy in 1978 and establishing special economic zones in the coastal Fujian and Guangdong provinces to encourage foreign direct investment. This shift was officially endorsed with the adoption of the Coastal Development Strategy in 1988, Golley says, and by 1995 the region accounted for 65% of industrial output in China. Historical, geographical and cultural factors helped make industrial bases there bigger and better than elsewhere.

“A ‘natural’ consequence of economic development is that it compounds these advantages, as improvements in transport linkages between regions make it possible for firms and workers to move to towns with the largest markets,” says Golley.

That can result in one region emerging as an industrial core that grows richer as other regions on the periphery lag behind—though Deng always intended coastal development to spread inland. He suggested that something would have to be done about it by around the turn of the millennium.

Policy Prophecy

Thus in 1998 the government of Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji began promoting a strategy of “Great Western Development”. The brunt of these reforms were aimed at getting provinces in the west of the country up to economic speed with their more advanced coastal counterparts. But the kind of economic environment that helped the latter thrive had already changed drastically.

That prompted Zhu to also embark on a campaign of radical reform in the state sector during the late 90s that laid off huge numbers of workers at state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which were either shut down or merged to make larger conglomerates. SOEs had always had a larger presence in China’s central provinces, and so they were hit harder by the new reforms than the private-sector-centric east coast.

Lu Ding, a visiting senior research fellow at the East Asian Institute of Singapore National University, says the draw of big eastern cities’ ample work and higher wages was and remains hard to resist for those living inland. “Generally those more prosperous areas attracted more capital inflow, labor inflow—not only investments, but a more productive labor force. It was a drain on the other provinces,” Lu says.

The SOE reforms also hit China’s northeast hard thanks to its traditional focus on heavy industry and reliance on government planning. In response, the government of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao announced a second regional development policy plank to “Revitalize Northeast China” in 2003. Shortly thereafter the Hu-Wen administration announced the “Rise of Central China” development drive with similar goals in mind.

Rugged Reality

These policy drives were supposed to make China’s less prosperous regions into booming economic belts. But when policy planners adopted market mechanisms, they also appeared to absorb other assumptions about growth that went unchallenged at the time—like the idea that any less-developed country or region could follow a universal route to becoming an advanced economy through industrialization.

Today those assumptions are under fire from skeptical development scholars who subscribe to concepts like dependency theory, in which perpetually poor countries provide cheap labor and natural resources to developed countries.

Under this rubric, developed countries seek to preserve their status by rebuffing attempts to level the playing field. When residents of China’s richer provinces protest suggestions they share education and welfare resources, they may be doing the same.

But more concrete are the physical factors obstructing policymakers’ idealized development. Historically, those include rough terrain that increases the cost of developing infrastructure and industry, distance from coastal hubs of commerce and the resulting isolation that limits the flow of resources. When China opened up, its export-centric model of growth oriented itself out and toward the West and away from its erstwhile inland Soviet ally.

Infrastructure can help, but it can also distract, and resource development can benefit those in the provinces being supplied more than local living standards. A quantitative analysis of GDP on counties bordering either side of the boundary delineating western provinces from the rest by Jeffrey Warner at the University of California San Diego’s School of International Relations and Pacific Studies found a positive effect of almost 20% on GDP resulting from Great Western Development policies.

Yet it also notes the boost may “only [be] demonstrative of increases in central government expenditures and not an increase in jobs or incomes.” Lu notes that is often the case. “[Inland provinces’] economic growth has been more or less driven by the energy industry and infrastructure development, but not much else from other parts of the economy,” he says.

Heading for the Hills?

The most significant measure taken to promote inland development might have occurred even before development of the west became a strategic goal. In March of 1997, the city and periphery of mountainous Chongqing was cordoned off from the rest of Sichuan province and turned into the fourth provincial-level municipality directly administered by the central government.

According to policy analysis by Lai Hongyi at the National University of Singapore, the move was intended to both facilitate the development of the Three Gorges Dam downstream on the Yangtze River and help the new administrative region spearhead inland development. But although Chongqing is now often referred to as the world’s largest city, in truth it is largely rural: its core urban area accounts for only about 1.1% of its land.

Chongqing’s 340-square-mile urban area has a population of only about 6.8 million, but its total population was 28.8 million as of the 2010 census, down 1.7 million from 2000 thanks to the emptying out of its vast countryside as rural residents left home—not all of them for the nearby city proper.

Economic growth in Chongqing has been driven largely by investment-driven manufacturing, but Golley notes that it has always been “one of (or the) best-developed cities out west” thanks to its own historical legacy. During the war with Japan it was an interim capital for the Republic of China to which many coastal factories relocated. She says its current stronger links to the central government also likely provide it with more lobbying power.

Yet even with historic weight to throw around, Chongqing lacks in foreign direct investment (FDI)—the kind that helped boost coastal provinces’ growth in previous decades—when compared to other municipalities under the direction of the central government. Beijing’s FDI was equivalent to less than half of Shanghai’s nearly $500 billion total in 2013 according to the State Administration for Industry and Commerce. But at just $58.8 billion Chongqing fell short of even half the FDI of third-ranked municipality, Tianjin. Indeed, Chongqing’s FDI only accounted for 1.7% of the national total that year.

Chronic Ailments

Not all the numbers for inland provinces come off as puny. Simon Zhao, an associate professor at the University of Hong Kong who specializes in urban and regional studies and planning, says that non-coastal provinces have done well in the past five years in terms of GDP growth.

“But currently things are bad because in the past five years, the so-called success of trickle-down development is in fact not that much [of a contributor] to the real economy,” Zhao says. “Rather, they are basically in land development.”

With the country stuck in what Zhao calls a deep recession, less developed regions are now in dire straits thanks to development policies that ignored provinces’ real economies in favor of lucrative real estate deals.

That’s on top of pay gaps. A 2013 study on the persistence of regional inequality in China by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco broke down the factors contributing to inequality in real wages. It found that during a sample period from 1993 to 2011, about half of the cross-province real wage difference could be explained by differences in quality of labor, industry composition, labor supply elasticities and geographical location.

China’s household residency permit—or hukou—system explained much of the rest. Imposed in 1958, this system’s main impact was on rural-to-urban mobility and cross-regional migration. Enforcement became less strict in 1978, but until 2003 a repatriation law meant that migrant workers could be forcibly returned to their home province and subject to fines and detention without the proper papers.

But while many provinces have all but abolished limitations on rural-urban migration, inter-provincial migration is still incredibly difficult, with the most populous urban centers like Beijing often adopting the harshest measures against migrant worker inflows.

Work and Wages

The San Francisco Fed also calculated the correlation between real wages and transfers from the central government to provincial budgets—only to find that there was none. In other words, as recently as 2013 funds dispersed to provinces for projects were not substantially improving local wages.

Meanwhile, the “Made in China 2025” (see the opposite page) program announced in February may put more pressure on inland provinces whose capacity for basic manufacturing is only beginning. The program is meant to move China’s manufacturing sector up the value chain by encouraging factories to produce higher-value-added products in fields like robotics. That means ending subsidies that favor low-end manufacturing and ratcheting up regulation.

“I’m not saying the government wants to get rid of traditional industries,” Stanley Lau, Chairman of the Federation of Hong Kong Industries, told news agency Reuters in June. “But with the actions they are taking and the policies they are launching, they’ll eventually kill traditional industries.”

Manufacturers that do move inland can get caught between government policy and market forces. In late 2014 a Wall Street Journal exposé revealed that because so many workers had left for work in more prosperous cities, at least 8 million students at vocational schools in Chongqing were being dragooned every year into “internships” at local electronics factories and forced to work for up to a year just to graduate—all sanctioned by the education ministry.

Thinking Long-term

While the government has signaled its intention to address these issues, it isn’t clear much can actually be done from a policy standpoint. Lu is generally skeptical that the central government could undo what market forces have done.

“For regional development in China at this moment, the important thing is [the provinces] all need to focus on their own real economies, focus on what they can do,” he says. That includes agriculture and mining, as well as new industries like biochemistry, he says.

Golley points out that policy can help drive migration as it has for the western province of Xinjiang. Zhao was careful to add that measures needed to be taken to address unrest in that region and others where ethnic minorities are clustered, which can stem from unequal distribution of development’s financial gains.

That is not to say China’s economic growth is destined to be undone by mounting regional inequality, or that the coast will remain the only rich region. It is true that strong growth in manufacturing labor costs driven by rising wages could undercut China’s role as a manufacturing hub. But a 2014 report by The Economist Intelligence Unit found that China remains highly competitive internationally, and estimated its labor costs would still be under 12% of US labor costs in 2020.

The report also confirmed that internal disparities in manufacturing labor costs were narrowing in China, suggesting that development policies based on assumptions about lower inland wages were unlikely to reproduce coastal successes. Regionally, China’s labor costs per hour are projected to grow to 177% of those in Vietnam and 218% of those in India by 2019. If these countries develop better supply chain infrastructure, they could attract substantial business.

But the report also singled out the less-developed provinces of Jiangxi, Henan and Hebei as attractive manufacturing destinations thanks to relatively low labor costs, more established infrastructure and large labor pools. That’s not quite the regional coverage Deng might’ve hoped for, but between them these provinces account for 16.5% of China’s population according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics.

Nor is persistent inequality unique to China: different parts of the United States also suffer from wage and wealth gaps. But Golley is not optimistic about a quick fix for the issue in China. “Whichever way that goes,” she says, “we’re not going to live to see a China without substantial regional inequalities in our time.”

For Chen, on the Bund, the fact that Chongqing may never look like Shanghai doesn’t seem too troubling. Asked if his hometown could ever feature a futuristic skyline like that on the Huangpu River’s opposite bank, he smiles and shrugs. “Chongqing is already very beautiful,” Chen replies.