The aging population in China needs a housing solution. So what’s stopping the industry from booming?

Since the beginning of 2014, Jim Biggs has been living in a brand-new residential facility for senior citizens with dementia. He’s just 54 years old, and has no problem with his memory. Biggs, the managing director of Honghui Senior Housing Management, is one of China’s senior living industry pioneers. An expert in elderly care services with 27 years of experience in the US, he is devoting every minute to making ‘Friendship House’ in Tianjin a success.

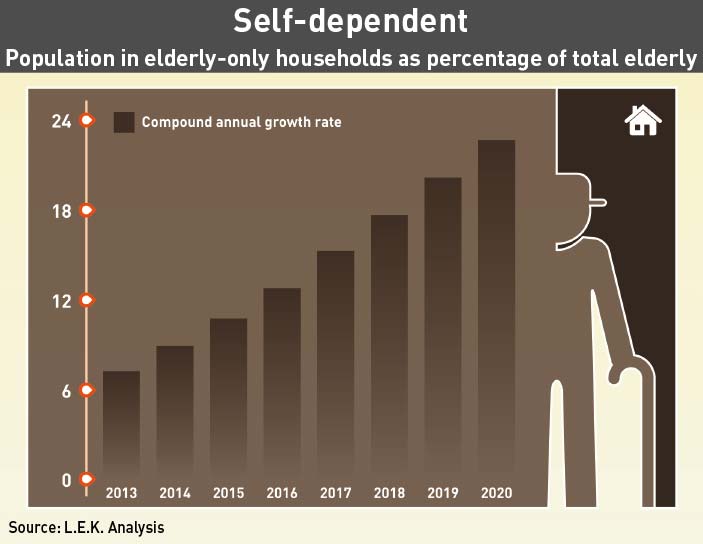

As yet, there are 20 empty rooms in the 26-bed facility, which opened in 2013. But he remains optimistic. Few markets can promise such high customer demand as senior care in China. By 2050, there will be more over-60s in China than there are people in the United States. And it’s these numbers that keep smiles on the faces of those battling to establish residential care facilities in the face of inconsistent regulation, cultural resistance and onerous bureaucracy.

Yet, the elderly care market in China is still in its infancy, despite the imminent demands of the aging population, and it’s still not clear what kinds of business models are best suited to help it grow up.

What Happens to Grandma?

At present, almost all nursing homes in China are publicly funded. According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, nursing homes across the country have a total of 4.16 million beds. But it’s not enough, says Biggs. “If you take a look at the demographics, even if they were to start building today the government wouldn’t be able to build enough beds for what they’re demographically anticipating they’re going to need. And they know this,” he says.

In 2013, Wang Hui, director of the Department of Social Welfare and Charity Promotion under the Ministry of Civil Affairs, said China needs about 10 million more nursing home beds.

In Beijing and Shanghai, all public nursing homes are filled to capacity, with long waiting lists. While nurses are also in short supply: there are only 200,000 in the country, with just one tenth holding nursing licenses.

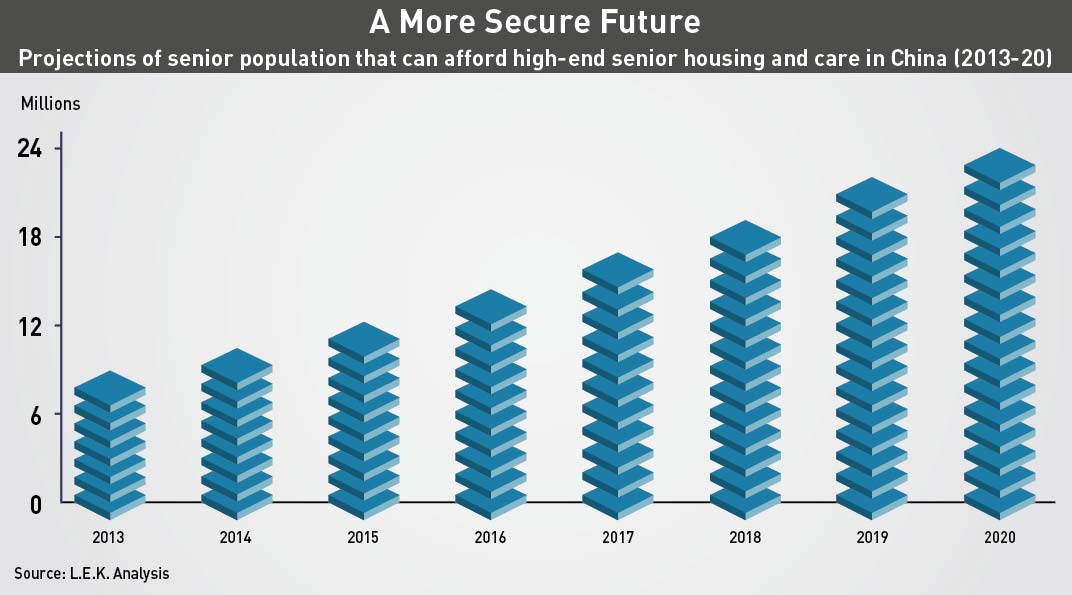

Benjamin Shobert founder and MD of Rubicon Strategy Group—a consulting firm specializing in healthcare, life science and senior care industries—works with governments and private companies to advise them on how to best access the world’s fastest growing healthcare market. “It’s the dirty secret of the industry, but right now most operators are saying to themselves that we’re probably 10-15 years away from having a viable customer base,” says Shobert.

According to Joseph Christian, fellow at Harvard Kennedy School, where he is researching the senior housing industry in China, there are simply not the pension benefits or other funding sources available to senior citizens to allow them to pay what companies want to charge.

“Health insurance is only just beginning to come into the marketplace, and I think the country has to have that before the market can really grow,” says Christian. “In Japan, the government introduced long-term care insurance in 2000 and that’s when the senior living market really began to take off.”

Japan has a similarly challenging aging care crisis on its hands, with one in three people predicted to be over 65 by 2030. In response, officials developed a part-insurance funded, part tax-funded care model— to perform alongside the existing health system—that could fund wide-ranging care for retirees.

Fourteen years later, the country now has a competitive market of provision that entitles seniors to everything from home help to residential care. In contrast, China’s national health insurance is by and large only applicable within public hospitals where resources are already strapped. Services that extend beyond the walls of the hospital are outside the scope of the insurance, also known as yibao.

Mrs. Lee, who preferred not to give her full name, arranged for her mother to live in Friendship House when it opened last year. Even though she is well versed in dementia care, she said she still had doubts. Despite Friendship House costing a fraction of the equivalent compared to other developed countries, she says that rent costing RMB 800-1,000 per month is still seen as too costly by many. Financial considerations are seen as the primary factor, says Lee.

“I believe I made the right decision. But before my mother moved in, I had some concerns regarding the level of care. I was concerned about her lack of ability to communicate with the caregivers, and whether this would lead to bad situations.”

Furthermore, Shobert observes that families are not yet feeling the full economic weight of having elderly relatives: “When the middle-class and upper middle-class sit down as a family and talk about who is going to stop their career to take care of mum and dad, then you’ll see the industry take off. But we’re not there yet.”

Experiments in Senior Care

Senior living projects coming out of the private sector fall into three main categories: real estate targeted at senior citizens, high-end or needs-focused residential care homes, and lifestyle-orientated assisted living complexes.

“What we really have today are a few examples of what should be seen as pilot projects,” says Shobert. “A bunch of people trying to figure out what is actually going to work, and it’s still pretty early on to be able to say definitively what we’re going to get out of that.”

The real estate senior housing model focuses heavily on providing property to an older demographic. However, insiders say, these (often Chinese-driven ventures) rarely have an accompanying emphasis on supplying healthcare services.

High acuity assisted living projects that focus on niche areas of the market such as dementia care—where the service need is clearly established—tend to be run by a wholly foreign-owned enterprise and joint ventures. At places such as China Senior Care in Hangzhou and Friendship House, the price will also reflect the expertise of caregivers.

Continuing care retirement communities (CCRC), such as Cherish Yearn and Starcastle (both on the outskirts of

Shanghai), focus on residents enjoying an enhanced lifestyle—restaurant style dining, in-unit housekeeping, shuttle service, planned activities—with healthcare assistance.

“I tell companies to focus on higher acuity models that are going to speak to needs that cannot be addressed with live-in help, like rehabilitation and dementia,” says Shobert. “I think you’re going to continue to struggle in the middle of the market, where you’re not clearly differentiating yourself on the basis of a healthcare need.” Mark Spitalnik, CEO of China Senior Care, runs a wholly foreign-owned enterprise in the senior care sector, and deliberately chose to create a needs-based product. His first high-end facility scheduled to open in Hangzhou later in 2014 will likely charge residents approximately RMB 40,000 per month.

Spitalnik points to examples of recent joint ventures between foreign companies and Chinese companies that have deteriorated because the Chinese side wanted a quick and profitable real estate flip while the foreign side insisted on the timelier pursuit of developing all the aspects of a fully equipped senior care facility. He notes Belmont Village and Life Care Services as two such examples.

“Most of the projects in China are driven by real estate. The developers are looking to do projects where they can develop and sell independent living properties, they’re not primarily driven by providing care to seniors,” says Spitalnik.

Biggs has also encountered Sino-foreign visions in discord. “It’s rarely a meeting of minds in the business sense,” he says. “In China they won’t just come out and say, ‘We just need you for the land. We’re not really into the senior housing, we just want to buy land at a discount because it’s for elderly care so we can build on it’.”

Regulation Chokehold

When it comes to regulation, the senior care industry fights against complaints common to Chinese legislation: a lack of transparency, consistency and constrictive licensing arrangements.

Experts say that in general the government is ‘pro business’ but modification of existing legislation can take time as it’s caught up in the middle of wider healthcare reform. Plus, there’s the perennial problem of a lack of coordination between provincial and central government.

According to Christian, the landscape remains almost impossible to negotiate without setting up a potentially unreliable joint venture with a domestic company. Spitalnik’s venture is an exception in Hangzhou.

“In the Ministry of Civil Affairs’ Measures adopted as of July 1, 2013, the government clarified and relaxed requirements of professional qualifications for staffing,” says Christian. “While previously, the requirements mandated certain levels and competency of personnel, the measures stated that a senior living facility needs to employ management, professional and service personnel commensurate with the services to be provided, thus allowing more flexibility in the operation of the facility.” You can also establish branches in other cities, he adds. But the Ministry of Civil Affairs will require a separate license for each facility.

“As the Ministry of Civil Affairs’ jurisdiction does not extend to the medical functions of the facilities, which require approval of the Ministry of Health, this creates some uncertainty for investors,” he adds. “However, it can vary from province to province, municipality to municipality and district to district. And even within one office, it’s possible that different people will have different views on things, so you have to make sure you find the right person to advocate senior living projects.” In addition, there are major obstacles when it comes to the issues of land.

In 2006 and 2007, the PRC implemented a restrictive policy on foreign investment in real estate to stabilize property prices and reduce renminbi appreciation pressures. “It’s safe to say that there’s a lot of work that needs to be done to clarify land right issues,” says Shobert. “Right now that’s probably one of the most problematic areas.”

Current regulations also make it difficult to bring medical staff into your facility. “Doctors and nurses need to practice in an appropriately licensed facility, which historically has been considered a ‘medical institution’,” explains Shobert, meaning assisted living facilities must meet the same regulatory standards as hospitals.

“The central government needs to populate a new body of regulations that addresses a less onerous regulatory standard for senior living than a hospital or “medical institution” would require,” says Shobert.

Then there’s the issue of finding staff if or when the medical license is obtained. China currently has only 300,000 caregivers and of these caregivers, just 100,000 have “professional qualifications”. Biggs says: “We had staffing issues and eventually just went straight to the local caregiver training college and hired the kids right out of school, and trained them up.” But recruiting physicians is not so straightforward.

“Young physicians currently employed by government hospitals have no interests in migrating to us,” says Michael Li, who runs the operations for senior living developer Cascade China, which has facilities in Shanghai and Beijing.

He adds: “One good thing about China’s mandated retirement age [60 male, 55 female] is the sector technically has plenty of experienced, high quality retired physicians ready, willing and able to participate in the senior care services—if their original employers okay the work with an official seal of approval.”

Retiring Gracefully?

Despite the sector’s enormous potential, experts say that investors are currently reluctant to place bets on this market.

“What everybody says about senior living in China is that there’s no proven business model. But there’s a real herd mentality, so when one starts and it seems to be successful then you’ll see a lot of people moving into the sector,” explains Christian. Last year, Chinese-owned firm Edward Healthcare, established a UK-based research center—The Edward Centre for Health Care Management Research—to work with the University of Manchester in exploring care systems, technologies and products that could be developed and adopted for use in China According to Jackie Oldham, Professor and Honorary Director of the center, the company brings a hotelier component to senior care.

“After all, why does it have to be an elder care facility, why can’t it be a holiday resort with specific facilities?” he adds. At this stage, industry regulation is relatively slight so there is room for genuine innovation and tailored products that meet the needs of the Chinese market. According to industry specialist Spitalnik, foreign companies can overlook the pressing cultural needs of Chinese consumers in their haste to impart expertise.

“For example, in China, if accommodation is too far away from the rest of a person’s family and friends, it will be very unattractive. Chinese people also like the idea that the family can live in or around the area where their family’s seniors are living.” Research has also found that affluent Chinese grandparents do not want to spend money on their senior living care. “They want to see money saved and directed towards the needs of the younger generations,” says Shobert. “Finally, one thing I always say to clients, is never underestimate the ability and the willingness of the older Chinese to suffer,” he adds. “If they live in a place without some amenities, it’s not going to strike them as particularly difficult. The senior living industry has to find a way to convince them they deserve more.”