China’s pollution problem has reached apocalyptic levels, which is great news for smart companies that have found a business opportunity in it.

Wang Bin browses a selection of facemasks at a supermarket in central Beijing. After scanning several different styles, he picks out an intimidating, thick mask made by 3M, an American conglomerate. He’s buying the mask as a replacement, he says, after he lost his last one.

Wang and his grandmother have experienced coughing fits of late, likely due to the smog. Such immediate and tangible impacts of air pollution have caused a psychological shift in the minds of many in China.

“The big change is that air purifiers have gone from being a luxury item for ‘health-conscious’ people to a mainstream purchase,” says Chris Buckley, owner of Torana Clean Air Center, a Beijing-based company that sells face masks, air purifiers, and other similar items. And mainstream purchasing means big mainstream profits.

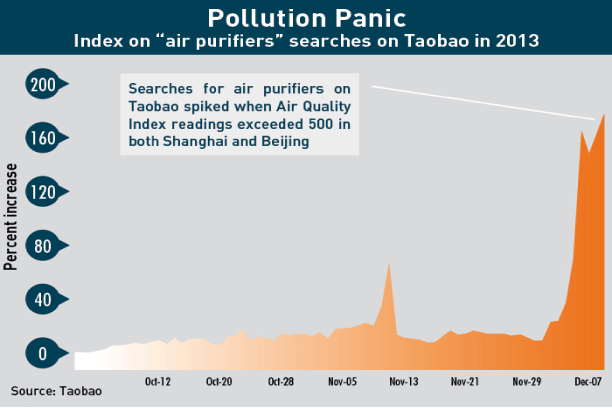

Nationwide sales of face masks on Taobao and Tmall, two of China’s most popular e-commerce websites, surged nine-fold in early December from the year before, according to state media. Home air purifiers were up three-fold.

China’s air pollution has grown steadily worse in recent years. “Airpocalypse” conditions—including more accurate and publicly available data on air quality—have spurred consumers to snap up products that combat air pollution. It has also pressured policymakers into passing tough new rules that require power plants and auto makers to install emissions-reducing technologies, mandate the construction of cleaner residential buildings, and many other measures. In September, for instance, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection issued a RMB 1.7 trillion ($277 billion) plan to combat air pollution by 2017 through various subsidies.

China’s air pollution, while undoubtedly harmful to the consumer’s body and bourse, has also created unprecedented demand for such air quality-related consumer goods and clean air technologies. As China’s smog will likely be here for a good while yet, savvy companies and investors are finding ways to turn smog into profits.

Deep Breath

Wang Bin has good reason to be concerned. Air pollution is often measured using concentrations of particulate matter under 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5), a level small enough to seep deep into the lungs. The World Health Organization recommends PM2.5 concentrations of no more than 25 micrograms per cubic meter.

Pollution in Beijing first exceeded the maximum levels of the US Embassy-provided Air Quality Index (AQI) (launched in 2008) in late 2010, topping 500 micrograms—a level initially labeled “crazy bad” by Beijing embassy staff (the post-500 category was quickly changed to “beyond scale”). That milestone has been surpassed many times since, and by early 2013 reached well over 800. Other northern cities have been hit even worse— Harbin registered levels above 1,000 in late 2013—and beyond-index pollution has even spread to southern areas such as Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang.

Smog that severe has clear health consequences. Air pollution cuts an average of five years off the lives of Chinese in the north of the country, according to a study published last year in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

China’s former health minister argued last year in The Lancet, a British medical journal, that between 350,000-500,000 people in China die prematurely each year due to air pollution. Independent studies, such as one also published in The Lancet in December 2013, put the figure as high as 1.2 million.

Local residents have taken note. Demand for air pollution-related products came in two waves, says Buckley of Torana Clean Air Center. The first was in late 2010, when foreign press coverage of the “crazy bad” air prompted many expats to buy air purifiers. The second came in late 2011, when stories about pollution began appearing with more frequency in local media and led to a surge of additional demand from Chinese consumers.

The combination has created a distinct change in how consumers view air quality products. International companies now routinely throw air purifiers into executive housing packages while big local companies, embassies and schools are installing heavy-duty air filters. (Some companies have even started paying their employees “pollution compensation”.)

China’s pollution has been good business for Torana Clean Air Center. Since its start in 2009, the company has established two brick-and-mortar outlets and significantly increased its online sales.

Manufacturers have enjoyed similar growth, especially international firms, which Chinese consumers tend to trust more than local brands. For instance, foreign brands comprise roughly 80% of the market for air purifiers in China, according to a study by Market Reports China.

3M, an American company that makes face masks, air purifiers and air filters, says it has witnessed a “dramatic increase” in demand from China over the past three years, according to a company spokesperson who declined to be named. The company has responded by promoting sales of its masks on Taobao and other Chinese e-commerce sites. But it “still can’t seem to provide them fast enough,” especially during the winter months.

Honeywell, another American conglomerate, says that “expanded government focus at all levels on curbing pollution will result in important commercial opportunities”. The company has seen its sales of air filters and purifiers increase by 50% over the past three years, says Roger Zhang, a company spokesman. Some companies, such as Broad Group, a Chinese manufacturer, estimate that the market for air purifiers alone could reach $33 billion by 2019.

One important source of growth, Zhang adds, has been business-to-business services, as commercial buyers—hospitals, hotels, train stations, and so on—look to upgrade their air filtration and purification systems.

Cleaning House

The desire to upgrade air quality has extended into the industrial environment as well. Power stations, manufacturers, and construction firms are all preparing to adopt cleaner technology to prepare for tougher emissions standards.

China’s State Council announced in September 2013 a raft of measures that included specific PM2.5 reduction targets for several northern cities. Ifthe targets are not met by 2017, said Beijing’s mayor at a press conference, “heads will roll.”

Local policymakers will need to focus on the three main sources of air pollution: power stations, industrial complexes and auto emissions, says Geoff Dollard, Director of Air and Environmental Quality Practice at Ricardo-AEA, a UK-based air quality and energy consultancy that advises Chinese cities on air pollution policies.

The government has taken major steps to curb pollution among the first two sources, he adds. Several incentive schemes encourage a shift from burning coal to cleaner natural gas and require retrofitting power stations to cut out pollutants. The government also announced in January requirements for about 15,000 small factories to produce real-time, publicly available information on emissions.

One beneficiary of such policies is LP Amina, a US-based tech firm that equips coal-fired power plants with technology to cut out nitrogen oxide (NOx), a pollutant. Demand in China for the company’s technology is “definitely growing,” says Jamyan Dudka, its Marketing and Business Development Manager.

One beneficiary of such policies is LP Amina, a US-based tech firm that equips coal-fired power plants with technology to cut out nitrogen oxide (NOx), a pollutant. Demand in China for the company’s technology is “definitely growing,” says Jamyan Dudka, its Marketing and Business Development Manager.

That demand is largely policy-driven. Over the past decade, each new Five Year Plan (FYP) has targeted a different type of pollutant at power stations. China’s 11th FYP, in effect from 2006-2011, took aim at sulfur emissions. The most recent 12th FYP, covering 2012-2017, is now doing the same for NOx.

After reviewing the latest FYP, “we knew there would be a big market so we decided to jump in,” says Dudka. The company currently has operations at plants in about 13 provinces, and its China sales doubled last year.

A typical project was the Shajiao Power Plant located in Guangzhou. The plant’s owners sent LP Amina several technical specifications of the station, including the capacity, existing technology, type of coal used and emissions target. After reviewing the specifications, LP Amina worked with the owner to choose one of its three main NOx technology solutions (each with a different price and reduction level).

The team then designed, purchased and installed the custom retrofit equipment for Shajiao Power Plant. The total time to completion was four months, compared to about a year in the US. “Just everything from engineering, procurement, to installation happens so much faster [in China],” says Dudka.

The market has its share of challenges, however. For starters, retrofitting is a one-off business: once power plants have acquired the latest NOx technology, the focus will shift elsewhere. Dudka says LP Amina is therefore working on other coal technologies, such as a system that sorts and classifies coal based on its particle size to introduce after its current retrofit projects are finished.

Another issue is corporate corruption, especially fake auctions. Big power station companies, many of which are government-owned, have learned that there is money to be made in the retrofit space and set up subsidiaries to focus on such work.

To maintain a veneer of above-board public procurement procedures, power plant companies open public bidding for firms to meet its retrofit requirements, says Dudka. LP Amina and others take time to create a proposal, but the winner (the power company’s subsidiary) was actually chosen before bidding even started.

Policymakers have also taken aim at retrofitting homes and offices to cut down energy consumption altogether.

China’s government has committed to making 30% of all new construction green by 2020—the government’s first concrete green construction target, notes John Mandyck, Chief Sustainability Officer at United Technologies, a high-tech US manufacturing conglomerate that is involved in green construction. By comparison, about 44% of all new commercial construction in the US is green, up from just 4% in 2005.

The definition of green construction can vary, but generally encompasses standards for water efficiency, energy-saving materials (such as double-paned windows), and indoor environmental quality. Officials estimate that new green construction will save the equivalent of burning 45 million tons of coal during 2011-2015, according to state media.

Moreover, the government has mandated that some four million square meters of property in several northern cities be retrofitted for better insulation against the cold. The retrofits should cut energy consumption by around 20-30%.

Several property developers in China are benefitting from the policies. Mandyck singles out Wanda, one of China’s largest property developers, as a particularly aggressive mover. The company is constructing 10 new commercial projects that have been certified green by the government. Foreign architectural firms have also been urged to design greener buildings, including Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which designed the Chemsunny World Trade Center in Beijing with double-paned glass.

Despite the challenges, the policies are working, argues Dollard. But unfortunately reduced emissions from power plants and industry have been offset by higher emissions from more autos on the road.

According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, about 22 million new vehicles were sold in China last year, up 13.9% year-on-year despite the slowing economy.

Policymakers initially hoped to combat increased emissions by encouraging the growth of electric cars and buses; Beijing set targets of 500,000 such vehicles on the road by 2015 and 5 million by 2020. But sadly consumers seem largely uninterested. Just 17,600 hybrid and all-electric vehicles were sold in China last year.

At the same time officials have been tightening emissions standards, which are “typically two years behind where we are in Europe,” says Daren Mottershead, Sales and Marketing Manager at MAHLE Powertrain, a UK-based firm that consults Chinese car makers on developing engines with lower emissions.

Demand in China for emissions technology and know-how has increased steadily in recent years, he adds. Not only are local emissions standards being steadily adjusted upwards, but Chinese manufacturers are increasingly looking to sell cars in markets with already high emissions standards, especially Europe.

Moreover, Chinese car companies have generally purchased previous-generation engines from US and European auto companies and then made small tweaks to comply with local regulations. Now they are looking to develop their own engines in-house, an undertaking that can be as expensive and time-consuming as designing the car itself. That gives companies like MAHLE Powertrain an opportunity to consult services on low-emission engines—a market that will continue growing strongly in future, says Mottershead.

Here to Stay

The assumption seems a safe bet: many experts believe China’s air pollution will stay for the foreseeable future.

“Effectively what China is going through is a very accelerated version of the problems Europe has faced,” says Chris Dodwell, Director of International Projects at Ricardo-AEA.

Air pollution experiences tend to follow a similar pattern, he explains. Pollution builds along with the region’s industrial growth. Eventually it poses a clear and unacceptable threat to public health, and a backlash—sometimes a single event or season—forces policymakers to crack down with tough legislation.

One such example was the infamous “Great Smog” in London during the winter of 1952, says Dollard of Ricardo-AEA. After around 4,000 residents died prematurely as a result of the pollution, parliament mustered the will to pass the Clean Air Act that cleared up the city.

China may soon be approaching a similar tipping point, analysts say. It could provide further opportunities for companies and investors.

“You walk outside in Beijing and not too many people are arguing whether or not you should have a clean technology industry,” says Ed Sappin, head of Sappin Global Strategies, a fund that invests in clean tech firms. “So fundamentally, from an investor’s standpoint, there’s going to be a big market in China for clean technology.”

In particular, Sappin points to smart grid technology as perhaps the next hot area for foreign investment, as China’s clean energy rules and subsidies push electricity providers to squeeze more out of their infrastructure.

But companies will need strong government relations that allow them to quickly sense shifts in the political wind. On the other hand, they need to maintain an innovation edge and avoid the temptation to bank on easy money from favorable regulation and government connections—connections and policies which can easily fade or change.

Despite hurdles, as an investor in the sector, Sappin says he is bullish and anticipates demand to grow in the long run.

“China’s market certainly is quite attractive at a macro level,” he says. “It’s really just a question of finding the right companies to partner with for the long term.”