E-books are heralded as the future of publishing all over the world. Is China blazing a trail or dragging its feet?

No one expected China’s electronic book scene to get so steamy in the spring and summer of 2013, but all of a sudden, E.L. James’ sexual thriller Fifty Shades of Grey was everywhere, though it hadn’t actually been published in China. Thanks to a market dominated by free or near-free content, strict censorship and rampant piracy, Fifty Shades of Grey has highlighted the tumult that is China’s e-book market.

The book had been translated for Taiwan and released in August of 2012, and through the use of popular file sharing platforms like China’s Douban.com, wound up on millions of Chinese computers, tablets, smartphones and e-readers. Eventually, the viral success of the book reached such heights that some mainland printers started printing pirated copies, using the same iconic cover art and selling via e-commerce platforms. It was a huge success, yet hardly anyone was making any money off of the steamy novel.

At this point, China’s e-book consumers are hardly willing to pay a cent for e-content, but many industry insiders believe there are signs of a change. China’s readers are poised to up their expectations of the reading experience, slowly shedding their tolerance for cheap file quality and lousy user interface. If that’s true, can a chokingly censored industry mired in struggles with internet control, a lack of investment in digital formatting, and copyright protection step up to the plate?

Not so Great Expectations

In 2012, the Chinese Academy of Print and Publication released its ninth annual survey of Chinese readers, indicating that consumers in China did not want to pay much more than $.50 for an e-book. And the average amount they pay for digital books can be far less than that. The average price for an e-book on Amazon’s Kindle Store, meanwhile, is $9.99.

The main bulwark of this low-to-zero price structure is China Mobile, the world’s largest mobile carrier by number of subscribers. China Mobile has a vast digital content catalog and allows its massive user base to access it for as little as $0.50 per month, which in turn sets the price standard for everyone else in the China market. Major platforms such as DangDang, Shanda, Baidu and Jingdong (JD.com, which was earlier under the domain name 360buy.com), have had to lower their prices to stay competitive.

“We’re not sure how the market is going to get itself out of this sort of all-you-can-eat payment model,” says Tyler Dimicco, Manager of Publisher Relations for the Asia-Pacific region of Tokyo-based Kobo, a digital content provider.

Publishers looking for the silver lining see China Mobile as a marketing tool.

“Data suggests that if white collar workers read a new, front list book that they buy from that platform, they are highly likely to go out and buy the book— and it becomes marketing. I think that’s been the way publishers view the China Mobile platform, as marketing, rather than revenue,” says Jo Lusby, Managing Director for Penguin China.

Dimicco concedes that for all of the monetization issues presented by a China Mobile monopoly, the Chinese carrier does a great job of making their content available no matter the hardware limitations.

“You [can] have a two-inch screen and you have to scroll constantly, and you have this sort of purple background with dark green text, it’s just horrendous, but you can do it. nongmin, people who have to ride the train for four hours every day with a sack of peppers tied on their back, they’re okay [with it]” says Dimicco.

Hard Knock Hardware

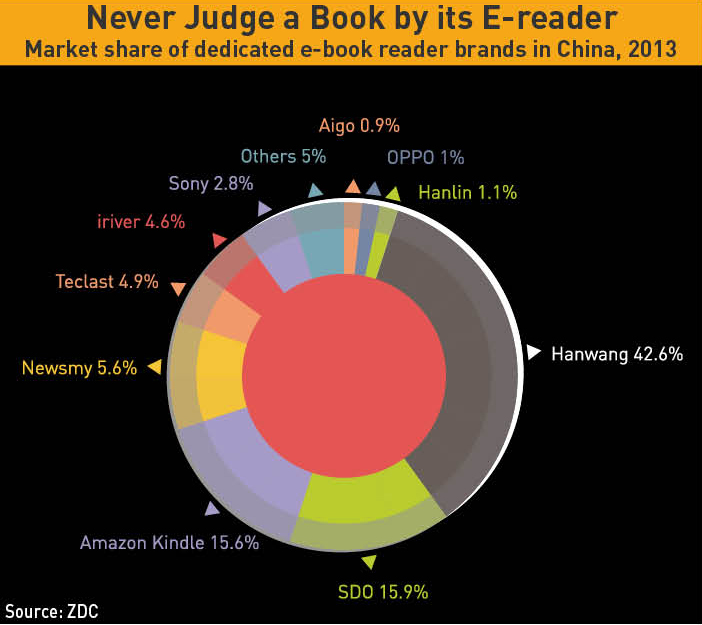

Dedicated e-book readers like Amazon’s Kindle, which have been so successful in the West, are rare, and the growing book reading capabilities of smartphones and tablet computers makes it unlikely that they stand a chance in China in the future, says Roger Sheng, Shanghai-based Electronics Research Director at technology research firm Gartner.

“Hardware wise, Kindle’s business potential in the future will still be limited, and will not reach the scale that it did in the United States,” Sheng says.

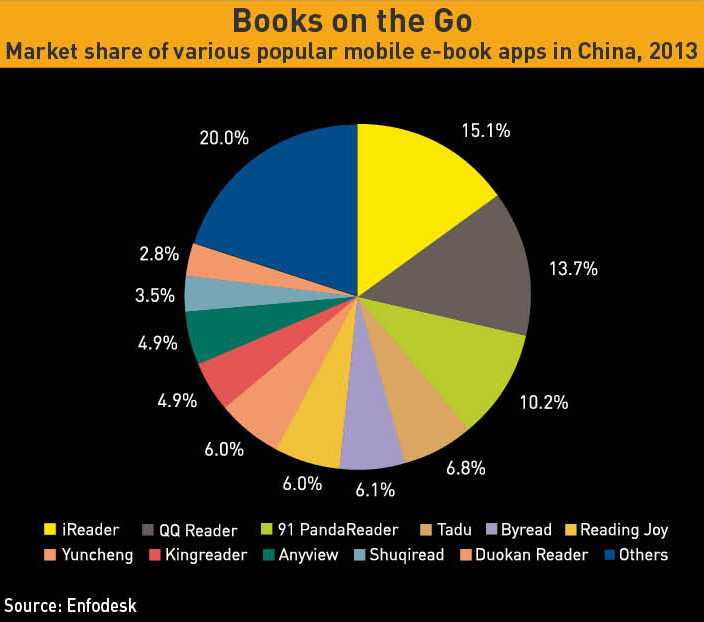

IDC recently lowered its global average forecast for e-readers by 14% between 2013 and 2016, given the research firm’s data on global shipments of e-readers show a 28% decline in 2012 from 2011 For most China consumers, it’s all about the apps. Market research firms EnfoDesk and Analysys International predicted in a joint 2013 report that the revenue of China’s mobile reading market in 2015 will be RMB 10.3 billion ($1.7 billion), and the number of active users will reach 650 million. The entire US e-book market was measured at $396.3 million by the Association of American Publishers in July 2013.

Furthermore, the most popular mobile reading apps, such as Zhangyue’s iReader (no relation to Apple), Tencent’s QQ Reader and Xiaomi’s Duokan, can be used on a wide variety of digital devices. Those on the tech side say that the big “aha” moment for the commercialization of China’s e-book market will most likely be owned by one of these providers.

Duokan is a home-court favorite, particularly since it was acquired by Chinese smartphone brand Xiaomi in January 2013. Xiaomi smartphones made headlines this year when market research firm Canalys reported that the Chinese smartphone took 5% of the domestic market, eclipsing the iPhone’s 4.8%.

Vice President of Duokan Hu Xiaodong says that Duokan has different content platforms that target different readers, dividing non-fiction from internet novels with separate ‘easy-to-use’ interfaces. Hu says what sets them apart from their competitors is “attitude”.

“Amazon includes all the e-books it can, while Duokan does more to guide users who may not know what they should read. We help users to choose the best book or the best edition of one book,” says Hu, adding that Duokan tries to stay away from basic file conversion. “If digital reading is going to develop, it needs to have its own independent system, instead of simply digitizing printed books.”

Lusby from Penguin Random House agrees, emphasizing that China’s technological capacity regarding written content is not the issue, but rather the gap between the technical advances, and what China’s publishers are willing to do with them.

Complicating matters is the fact that China’s publishing industry is highly fragmented, with roughly 40 main publishers—all ultimately state-owned—as opposed to the US market’s big four. China’s main e-book providers have also not been given the same kind of top-down policy directives from China’s General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP) that the main state publishers have.

“They were left to go off on their own and just do it, but without real input or direction. Because the market is highly fragmented, none of the players are big enough to have leverage on pricing and terms. As a result, you find publishers are reluctant to invest in new formats and engage with the platforms.” Lusby says. “What they’ve been doing is gradually making books available in digital form—which are pretty much unchanged from the print—and so the local content market has been under served.”

Orwellian Woes

China’s traditional publishing ecosystem has two distinct pillars. There are the publishers, all directly owned and controlled by the government, and then there are the “culture agencies”, outside companies which produce much of the content and then send their files to an officially registered publisher, who licenses, prints and distributes the product.

E-books are theoretically subject to elaborate approval protocols. All e-book providers must register with, and seek approval from, the authorities to distribute content, and all content is subject to the same rigorous review as printed content. If e-book traders from abroad want to sell foreign content in China, they have to initiate a multi-year process where finding the right Chinese partner is only step one.

“It would be a massive undertaking for us to offer English books into China directly,” Dimicco says. After altering all of their major publishing contracts, Dimicco says “we would have to sign on a Chinese entity, and then we’d have to send our books that we got from the publishers to the Chinese company, have them vet everything, run it through their database of forbidden words, and then have them send it back to our new servers in China after they’d done that check.”

But another option is to ignore official channels altogether and maintain a low key approach. Taiwan’s Readmoo.com has been quietly selling e-books to mainland China readers for a little more than a year now without being blocked.

“We are not that big, so the Chinese government hadnʼt used the Great Firewall to keep us outside of China at the beginning so people were accessing our website without issue,” says Sophie Pang, CEO of eCrowd Media, parent company to Readmoo.com, adding that there was no reason to block the site before because there was nothing provocative about the platform.

Pang takes the recent block in stride, adding that she had expected them to “gradually find out,” and only 8-9% of their consumers were from mainland China.

The supply gaps in the mainland content market have given birth to a well-established tradition of online literature.

E-epics

Online literature, or content that has been written specifically for the internet, has been booming for 10 years or more, according to Lusby.

Qidian.com, a subsidiary of Shanda Entertainment’s Cloudary, allows users to download content for free up to a certain word limit, and then charges RMB 0.01 for every 1,000 words. The writer gets 70% of the revenue and Qidian keeps the rest.

The results of this approach have been investment-worthy. In July of 2013, US investment firm Goldman Sachs and Singaporean investment firm Temasek jointly purchased a minority stake in Cloudary for $110 million. Another plus for Cloudary is that aside from investment from foreign firms, online literature has almost no foreign players. Cloudary, which consists of 1.6 million members and six million titles as of 2012, has an agreement with China Mobile which names the telecom giant as the only platform allowed to sell and distribute Cloudary’s content, other than Cloudary itself, according to Dimicco.

Penguin’s Lusby says that such content trends heavily toward young adult, fantasy and romance stories. The pricing of online content is often pegged to its popularity—the more popular, the higher the price. Content providers like Kobo can use this platform to see which books are of interest to the readers, and relay that information to authors when their manuscripts are in need of guidance.

“There’s a huge opportunity to create books that stay interesting up until the last word,” says Dimicco. Apparently the need to keep content interesting was so keenly felt that it compelled Qidian founder Lou Li to cut copyright corners, resulting in his arrest for copyright violations and bribery in May of this year. Despite the blight on Qidian’s reputation, Lou’s untimely arrest may have been just the bargaining chip that Goldman Sachs and Temasek were seeking.

Piracy, Friend or Foe?

In April of last year UK-based sci-fi/fantasy e-book platform Tor Books announced that it would be removing digital rights management (DRM) software from its ebooks, reasoning that piracy is mainly perpetrated by a cash-poor constituency that wouldn’t have bought the books anyway.

In May of this year, Tor Books revisited the issue and announced that the removal of DRM resulted in no discernable difference in piracy.

“If a publisher wants to distribute without DRM copyright protection, we can do that,” says James Bryant, CEO of Trajectory Inc., a Massachusetts-based e-book provider. “It would be a hard path to take, unless it’s a tack to introduce people to the book.”

The Asia-Pacific director from one prominent e-book platform, who asked not to be named, said if translating for the Taiwan market, while not perfect reading for the mainland given the difference in characters, there is a potential for the content to go viral via underground channels. “We would love to see that,” he says.

How much of a role foreign publishers can hope to play in the China market is open to question.

“We’ve been looking at the China market for two years now, and there’s definitely a reason that we haven’t jumped in yet,” says Dimicco of Kobo, citing the long content vetting process employed by GAPP and the monopoly of China Mobile as a few key reasons.

Playing Ball with Big Brother

Trajectory announced a partnership with state-owned Zhejiang United Publisher’s Group in October at 2013’s Frankfurt Book Fair, the culmination of a 20-year courtship of the appropriate government representatives and offering global distribution potentials for Chinese content.

“Relationships are really the key, and the true sense of the Chinese preference of doing business as a way of cooperating, where the Chinese can see the opportunity to partner with an outside company in a way that helps them achieve their goals. Then it’s a lot easier to establish a dialogue,” says Bryant.

In May of 2012, BIZ Peking, the representative office of the Frankfurt Book Fair in Beijing, released a state-of-play report on China’s publishing industry. The report iterated the main channels for access to foreign publishers, and the opportunities and challenges therein.

Foreign publishers have two options for selling books directly into China. They can initiate a one-time cooperation or coproduction with a Chinese partner revolving around a single title, or establish a joint venture where the Chinese partner holds the majority stake.

As the BIZ Peking report notes, joint ventures have suffered a myriad of complications over the years, the more notable of which include delays in payments to foreign publishers as the Chinese companies first need to apply for settlement in a foreign currency, and a drawn out decision making process as bureaucratic obstacles need to be overcome time and again.

Keys to the Kingdom

As Lusby and Duokan’s Hu explain, publishers that step to the forefront of the latest digital content technology will be able to set the market, and when it comes to platforms, Xiaomi is a strong contender. In addition to favorable market share, Xiaomi has access to all that juicy pulp literature that Chinese online writers are producing in bulk, which Goldman Sachs and Temasek evidently deem quite significant.

This is a major advantage over other contenders that veer either all the way toward digitizing printed books, what publishers typically do, to those that deal only in internet novels like Cloudary. For the consumers, publishers should find ways to develop a synergy with the platforms most invested in the user experience.

“The issue with China’s e-book market is not a technical one, but a human one,” says Lusby. “Chinese readers will pay what they want to pay for, and it’s about giving them that choice.”