How private Chinese companies are navigating mergers and acquisitions in the US.

At times, the obstacles seemed insurmountable. The acquisition of A123 Systems, an American manufacturer of lithium ion batteries, by a Chinese auto parts maker named Wanxiang triggered vehement opposition in the US.

Lawmakers protested that the technology being sold to the Chinese had been developed with $132 million of taxpayer money. Retired military officials warned that the transfer abroad of the company’s advanced products, used in energy grids, unmanned aerial vehicles and pulsed power weapons, could put American national security at risk. Local competitors interested in acquiring A123’s assets for themselves added their voices to the chorus. To reassure the American public, Wanxiang excluded A123’s defense contracts from its bid; these were sold separately to an Illinois-based company. But the criticism kept coming.

Yet American regulators approved the acquisition in January 2013, and the deal ultimately went through. A123 became part of Wanxiang’s 6,000-person workforce, more than half of which is located in the US.

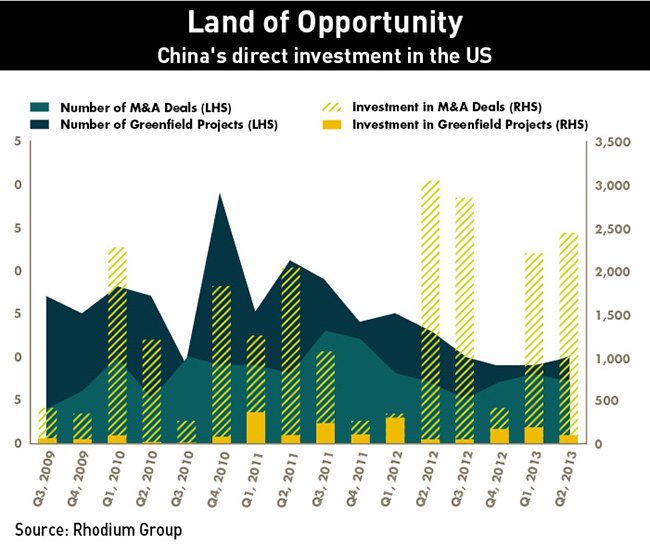

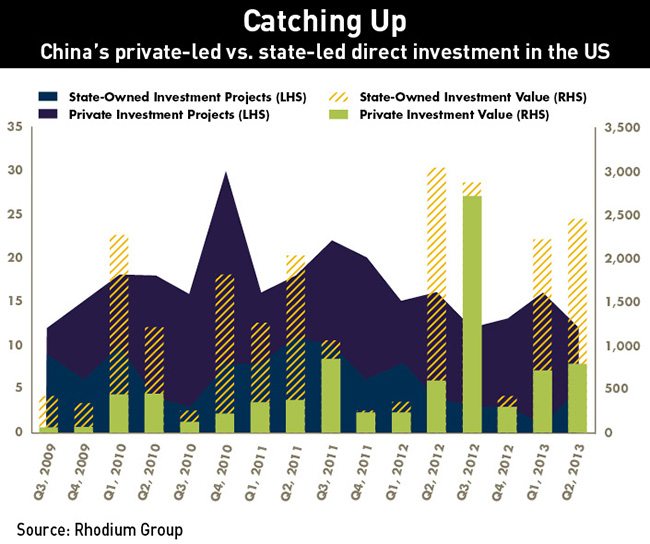

The deal was just one data point in a recent upswing in private Chinese investment in the US. According to private research company Rhodium Group, Chinese companies completed a record $4.7 billion in transactions in the US in the first six months of 2013, the strongest first half ever recorded. Furthermore, recent data show a dramatic increase in investments by private enterprises. From the beginning of 2012 through the second quarter of 2013, private firms conducted 84 investments totaling $5.39 trillion in the US, compared to 24 deals for a total of $6 trillion by state-owned firms, according to Rhodium Group data.

The floodgates appear to be opening to meet the growing demand from private Chinese firms for assets, and the US demand for capital. Obstacles remain, but formerly unsophisticated Chinese firms are increasingly following the lead of companies like Wanxiang in figuring out how to allay security concerns, dodge public relations crises and successfully make deals in America.

Go Forth and Multiply

Private entrepreneurs are increasingly taking the lead over China’s state-owned enterprises when it comes to US investment. From the beginning of 2012 through the first quarter of 2013, private Chinese companies spent more on US investments than in the 11 previous years combined, according to Rhodium Group, with 16 of the 17 acquisitions in the first quarter of 2013 done by privately-owned firms.

The Chinese share of investment remains small compared with overall stock of US investment—only about half a percent of inward FDI—but that’s set to change. More than $10 billion worth of Chinese deals in the US were pending as of July, according to the Rhodium Group.

“The US has everything you want,” says Derek Scissors, a Senior Research Fellow at The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that tracks Chinese outbound investment. “In principle, most sectors in the US economy are attractive to one or another kind of Chinese firm.”

Scissors separates private Chinese companies into two main groups: smaller private Chinese companies who are seeking to “get out of China entirely” and gain access to US customers, and larger private companies seeking technology, brands, resources and expertise to take back to China—such as Shuanghui International’s bid for Smithfield Foods in May, or Dalian Wanda, which struck a deal to acquire US cinema chain AMC Entertainment Holdings last year.

Growing political support at home has also been working to clear the way for private companies, including the government’s effort to provide some of its ample foreign currency reserves to companies making overseas acquisitions, says Teng Bingsheng, Associate Professor of Strategic Management at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. Once a deal has approval from the Ministry of Commerce, the company can apply to China’s state-owned banks for a dollar-denominated loan, he says.

Certain Chinese industries also get better treatment in the Chinese stock markets, Teng adds, giving them more cash to play with in cross-border investing. Teng cites the Shuanghui-Smithfield deal as an example: Agricultural companies receive higher valuations in China than in the US, giving them bigger cash reserves to field US acquisitions.

Suspicious Minds

Yet most Chinese companies and M&A advisors readily admit deals still face many potential pitfalls. More than $34 billion of potential Chinese acquisitions in the US have fallen through due to “a nasty surprise of some sort”, Scissors of the Heritage Foundation wrote in a note entitled “China’s Global Investment Rises: US Should Focus on Competition.”

To buy a US entity, potential Chinese acquirers must clear two official approvals: an examination of any potential national security risks by the Committee on and an investigation into anti-competitive impacts by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission.

Chinese companies can receive more scrutiny in these approval processes than acquirers from other countries because of fears that China’s loose rule of law and independent courts leaves companies more susceptible to government manipulation, says Thilo Haneman, Research Director at Rhodium Group. “Without rule of law, the government ultimately can manipulate private and state-owned enterprise alike.”

Even so, these approvals are not a significant obstacle for most Chinese acquirers. Only a handful of acquisitions are rejected due to national security concerns, most often in the sectors of advanced technology and telecommunications.

Chinese companies have also seen deals rejected because of their location, as in the case of the failed purchase by Ralls Corp of four wind farms in Oregon near restricted US naval airspace. Ralls, which belongs to two executives of privately owned Chinese construction company Sany Group, purchased the wind farms without reporting the transaction to CFIUS. Based on CFIUS recommendations, US President Barack Obama then issued an executive order requiring Ralls to divest its purchases, the first such order in 22 years. Ralls sued the president in September, claiming that the order violated its constitutional rights, but its case was overturned.

“That was an obvious red flag for an experienced CFIUS lawyer, but the company never consulted a lawyer about CFIUS in the first place,” says Haneman. “If you handle it well, [if] you have the right lawyers, private firms usually do not have problems with identifying those risks and mitigating them.” Ironically, the erroneous perception that these security reviews pose a significant obstacle is a greater barrier to would-be acquirers than the approvals themselves, says Haneman.

Part of the reason for this perception is undoubtedly the nature of the American public environment, in which politicians and journalists actively question potential risks to national security for Chinese companies of all stripes. To Chinese companies, this loud and usually critical conversation may make it seem like deals are doomed to fail.

But the CFIUS review itself is a straightforward procedure, says Pin Ni, the President of Wanxiang America. “We just need to respect the system. We’re in a democracy, and in a democracy everyone can have an opinion,” he says. “The press will talk about it, Congress people will step in. In a democracy, that’s their job. What you really need to deal with is CFIUS.”

Some Chinese companies more experienced with operating in the US are beginning to take initiative to assuage popular suspicions. Wendy Pan, a partner in O’Melveny & Myers LLP’s Shanghai office, who advised Chinese genomics sequencing institute BGI-Shenzhen during its acquisition of Complete Genomics, says her firm counseled the Chinese company to take a proactive strategy to minimize regulatory and PR risks. One such risk came from US-based competitor Ilumina, which claimed publicly that the acquisition was doomed to be rejected by CFIUS, which is the opposite of what ultimately happened.

“Since gene sequencing is such a cutting edge technology, it can be easily misunderstood by or misrepresented to the public,” says Pan. She and her colleagues advised BGI-Shenzhen to file voluntarily for CFIUS clearance, as well as publicize BGI’s previous charitable work with American non-profit organizations such as the Gates Foundation and Autism Speaks.

For less experienced Chinese companies, navigating America’s independent and dynamic media environment can still be a challenge. Many Chinese companies prefer to keep a low profile at home to avoid unwanted attention from the media or government regulators, and when they go abroad, they tend to continue those practices, says Pan.

“There’s a Chinese saying, ‘Ren pa chuming, zhu pa zhuang,’—people are afraid of getting famous, just like pigs are afraid of getting fat … Chinese companies do not like to talk openly about strategies, business visions, business plans. In Western business culture, this is unusual. So some misunderstandings are caused by the [different] business style,” Pan says.

Not all PR campaigns launched by Chinese companies have proved helpful to their fortunes in the US. CKGSB’s Teng cites the example of Huawei: the Chinese telecom company became the target of an aggressive campaign by US IT infrastructure company Cisco after Huawei ran ads in the US featuring the Golden Gate Bridge, suggesting there was no difference between its products and those made by California-based Cisco, whose logo is based on the Golden Gate Bridge.

In general, however, Chinese companies are getting savvier in their ability to launch PR campaigns. This may help to allay popular fears about Chinese companies and reduce political opposition at the Congressional level.

Caveat Emptor

The major barrier for private Chinese companies looking to invest in the US is not the national security approval, but institutional or experiential barriers. As relatively new entrants to the US market, Chinese companies are still learning how to properly navigate America’s dramatically different institutional and media environment, which is based on rule of law rather than personal relationships.

“Do you have a lawyer, how are you going to get your land zoned, how are you going to pay your taxes? I don’t think [Chinese companies] know how to do most of these things,” says Scissors of the Heritage Foundation. “They overestimate the gate-keeping problems in the US and they underestimate the operating problems in the US.”

In addition to cultural and managerial differences, companies without US experience may face operational challenges stemming from a gap in knowledge and experience between them and the target company. “When [Chinese companies] go out to acquire an American company, they face a difficult challenge, which is that the target tends to have a better system than the buyer. So what do you do with that?” says Teng of CKGSB.

For many Chinese companies, the initial strategy has been to leave the target company and its management system intact. But in the case of targets that are already struggling, this is often an imperfect solution.

Chinese consumer electronics maker TCL learned a hard lesson in this regard when it acquired Thomson’s TV business in 2005, says Teng. “They left it alone for one or two years, and [by the time] they realized the French management had run out of options it was too late for the Chinese management to do anything. It cost billions, and the acquisition was a total failure,” he says.

But Chinese companies are showing growing confidence in guiding their acquired companies. Wanxiang America President Pin Ni echoes this idea when talking about the lessons his company had learned from its more than 20 acquisitions in the US. Compared with when it began making acquisitions, Wanxiang’s greater experience and confidence now gives it the flexibility to do deals where they bring in a new management team to support the company. “We can do deals that have a little more risk involved,” Ni says.

Teng sees Chinese companies gaining the experience to work with a broader range of targets in the future. “Some very interesting companies may welcome strategic investors, but not sell right away. That means you have to get in through some kind of alliance first, and then if the two parties work well together, that may lead to an eventual acquisition down the road,” he says.

Private Chinese firms are proving quicker to adapt than their state-owned counterparts, says Haneman of the Rhodium Group. “We have seen a lot more sophistication over the past two or three years, especially on the Chinese side, in finding the right partners and the right strategies for navigating overseas regulatory environments,” he says.

By and large, struggling American companies still look to Chinese investors for liquidity, and not much else. But that is slowly changing. As Chinese companies learn to flex their own managerial muscles and capitalize on domestic markets and resources, acquiring Chinese firms can offer their targets more than much-needed cash. They can represent new life in every link on the value chain.