Can Western retail brands make it big in China’s e-market?

In September 2012, The Home Depot announced that it was closing all seven of its megastores in China. After eight years of consumer research and a $100-million 12-store acquisition, The Home Depot called it quits in China after realizing that China isn’t a sure return on investment. Speaking at the 2012 Reuters Retail and Consumer Summit in New York, the company’s Chief Financial Officer Carol Tome said that its brick-and-mortar retailing model “wasn’t meeting the needs of Chinese consumers”. Even while it was making this move, the beleaguered home furnishings retailer had already started selling goods on China’s 360buy.com—one of China’s leading business-to-consumer e-commerce sites. It also announced it was trying to partner with other Chinese e-commerce platforms.

The Home Depot is one among several foreign retailers now seeking to deal with setbacks in their Chinese brick-and-mortar ventures by capitalizing on the explosive growth of e-commerce in China, albeit one step behind their Chinese competitors.

The foreign big box retailer game in China hasn’t been as straightforward as hoped, and e-commerce offers a quick reach and requires significantly less capital.

Electronics retailer Best Buy also closed all of its megastores in China last year after dismal sales, opting to set up a space on Alibaba’s Taobao Mall (Tmall. com), China’s biggest e-retail platform. Retail giant Walmart, in the face of rising competition from foreign supermarket retailers, and declines in store visitors, acquired a 51% stake in the online supermarket Yihaodian in October 2012.

While companies like The Home Depot and Best Buy turned to e-commerce only after their brick-and-mortar stores all but failed in the Chinese market, others such as fashion retailer Zara, which has tasted success in China, are simply trying to capitalize on the online retail boom. And there are yet others, like US retailer Macy’s, which do not have a physical presence in China yet and are tapping the market via e-tail. One benefit of e-commerce in China is that both flops and successes skirt the increasing costs of real estate and the political tango it can involve.

The efficacy of the various e-retail strategies adopted by Western companies is still being weighed, but some have greater risks and execution challenges than others.

The Broad Shoulders of Tmall

E-commerce is becoming an indispensable part of any company’s China-business model, and with good reason. According to the Boston Consulting Group, e-retail sales should triple over the next three years, rising from $120 to $360 billion by 2015, when e-commerce will account for nearly 10% of all China retail sales.

There are three discernable strategies currently at play among multinational companies vying for e-retail action in China; partnering via equity purchase, piggybacking via Tmall, or going it alone by establishing a dedicated website.

One, and perhaps the fastest, strategy common among well-known Western MNC retailers breaking into e-commerce in China is reserving space on China’s biggest web platform, Tmall. In addition to Best Buy, others including British retailer Marks & Spencer, The North Face, GStar, and Ralph Lauren, have set up shop on this virtual mall.

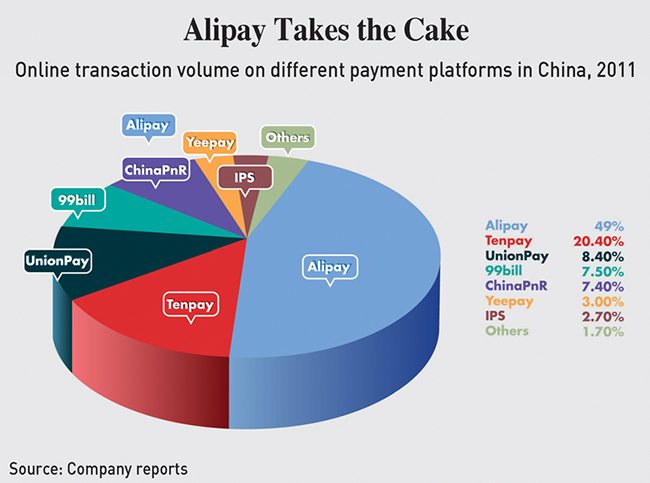

Getting on Tmall has some clear attractions for big-name Western retail brands. With RMB 200 billion ($32.1 billion) in sales in 2012, it is China’s biggest B2C online platform, and market research firm Euromonitor predicts it will soon displace Amazon.com as the world’s number one e-commerce site. The Alipay system, which surpassed the US’ Paypal in 2010 as the world’s largest third-party payment platform, is another feature of Tmall attractive to Western companies (Alipay was created by Alibaba, Taobao’s parent company). Lastly, the site has also been investing heavily in upgrading its supply chain and distribution system, so as to match 360buy.com’s same-day delivery guarantee. Quick delivery has become increasingly important in e-consumer motivation to shop online.

But Tmall has genuine risks. In 2011 retailers on the site protested after customers complained about receiving counterfeit products purchased at premium prices, and received support from the Ministry of Commerce. In reaction, Alibaba founder Jack Ma sharply ratcheted up service fees to drive out marginal vendors and improve Tmall’s image.

Even if this move succeeds—the presence of an upmarket-clothing brand like Marks & Spencer on Tmall might deal a blow to its brand equity, as the platform features stores of all sizes selling everything from sportswear to groceries. In China, the equity of foreign fashion brands stems from the idea that Western brands are of superior quality. This is especially true for the affluent Chinese consumers Marks & Spencer is targeting.

Take Fang Jie, a 40-something chief account manager at New Alliance Chinese Global Communications firm. She says, “I don’t buy anything local, only foreign brands, as Chinese brands are cheap and shoddy.”

Awareness of brand delicacy may be a contributing factor to Marks & Spencer’s two-pronged approach. In addition to its space on Tmall, the clothing store incorporated a dedicated Chinese website into its China e-tail strategy, which it launched in January.

Going it Alone

Even successful foreign retailers like Zara, which has 127 stores in China (not including sister stores like Zara Kids) according to parent company Inditex, have set up their own dedicated Chinese web stores to assume control over style and image projection. Toy retailer Toys ‘R’ Us has also implemented its own China site.

The Zara and Marks & Spencer e-retailing approach of going it alone forgoes the task of finding the right local partner, but the standalone approach presumes that Chinese shoppers will not just stick to familiar sites when buying online, but also venture new online shopping experiences. China-specific online sales figures for Zara and Marks & Spencer haven’t been released yet, but the experience of other foreign retailers with new and unique specialty offerings speak of a positive outlook for online newcomers. Ernie Diaz, the founder of Web Presence in China, which helps foreign companies build their own e-retail sites, explains that the somewhat surprising ease of setting up a website and payment system opens the doors to an array of companies offering niche specialty items.

“For a few thousand dollars, companies can set up an e-commerce account with a Hong Kong bank and then their customers can pay for goods with Alipay or 99pay,” says Diaz, dispelling the notion that Chinese online payment behaviors are difficult to crack, such as a lack of credit card ownership among e-shoppers in lower-tier cities.

Diaz further notes that Chinese banks are “promising in the next year to provide the ‘mobile wallet’ payment solution that exists in Japan for shoppers”. This new payment solution, which has been gaining ground in several developed markets, will enable online buyers to use their mobile phones to do the bank transfers required for online purchases. One certainty about the future of Chinese e-retailing is that payment logistics will soon become much simpler, which is good news for Western MNCs trying to crack open China’s digital sales market.

By developing one’s own platform, the task of finding the right Chinese partner is alleviated and company brand and aesthetic are maintained. But there are image-conscious Western retailers that are seemingly getting the best of both worlds.

Web Synergy

Macy’s, which has no physical presence in China, may have made the right move by partnering with VIPStore to get on Omei.com, a recently established online retailer that bills itself as the first choice for retailers in the US and Europe, even though it reaches far fewer consumers (2.5 million) than Tmall.

J. Crew similarly opted for a style conscious online partnership with Lanecrawford.com, a retailer of upmarket clothes and home furnishings, which helped it make Hong Kong one of its top five markets in 2011. The Macy’s and J. Crew approach underscore the importance of this web synergy for high-end brands, should they go the way of partnership. But it’s not only high-end brands that are investing in their partnerships, but also high-spending companies, such as Walmart.

Walmart continues to post double-digit sales growth in China, but the number of store visitors is down 7.1% between 2011 and 2012, according to China Market Research Group. The slip reflects rising competition from other big-box retailers. Despite having over 350 stores in 140 Chinese cities, Walmart is not achieving the level of same-store visits as competitors RT Mart and Carrefour. After last year’s pork mislabeling scandal in Chongqing, Walmart favored a more centralized top-down approach to management, which counters the point of RT Mart’s success precisely because it cedes control to store managers. There is also a problem between Walmart’s brand in the West versus its capacity in China. It won’t be the cheapest option for everyday goods for the China consumer, as it claims to be in its home country, so it may need to focus on the quality of living aspect of its brand to really hit China’s upwardly mobile.

Walmart recently acquired a majority stake in Chinese e-retailer Yihaodian. While the financial details of the deal have not been disclosed, it is being seen as a key pivot in both its branding mission and logistical operations.

Yihaodian, which was launched in 2008 and mainly sells fast-moving consumer goods, including groceries, is an attractive digital partner for the US retailing giant for a number of reasons. The online store now claims 24 million registered users and its sales have soared from $6 million in 2009 to $420 million in 2011. The retailer has invested heavily in technology and supply chain management, enabling it to provide same-day and next day delivery service. Twenty-three-year-old Liu Xue, employee of Chinese PR firm Evision, says that she prefers Yihaodian over shop-ping herself. “I’m really busy and don’t have time to shop, so Yihaodian is very convenient, plus the quality of their food is quite good,” she says.

But there are questions surrounding Yihaodian. First, its supply chain is most developed in the Yangtze Delta, which accounts for 70% of its orders. With the big growth in e-retail set to occur in cities, Yihaodian will have to make further heavy investments in its supply chain and sales management system to follow the growth.

More worrisome, despite its skyrocketing sales, Yihaodian has yet to break even, much less make a profit. The company estimates it will break even when its revenues hit $1.6 billion in two or three years.

When Yihaodian begins making money, Walmart will face legal constraints on its new partnership. Concerned over its impact in generating excessive market power for Walmart, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce stipulated that the Yihaodian acquisition be confined to the online retailer’s direct sales segment.

But according to Professor Wei Jiang of Shanghai Jiaotong University’s Antai School of Economics and Management, Walmart made the right decision.

“Acquiring Yihaodian is a smart move by Walmart that will give it a good presence in Chinese e-retailing,” he says. “Yihaodian is unique in China, there are no other online stores selling a wide variety of merchandise, the other e-retailer are either platforms, like Tmall, or have a narrow range of offerings, like Suning and Gome.”

In aligning with Yihaodian, Walmart has not just partnered with a smaller Chinese e-retail version of itself, but has also rendered competitors, such as Tesco, unable to compete using a similar strategy.

A Digital Oasis?

“I am not sure how e-retail will solve the basic issues of variations in merchandising and pricing needs in various markets. However, what it can do is reduce the burden of minimum scale and associated costs to enter a market. It can also allow the foreign retailers to avoid having to deal with the local real estate market, which is often not very transparent and fraught with political and economic challenges,” says Krishna G. Palepu, Ross Graham Walker Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School, and co-author of Winning in Emerging Markets.

Examples of the challenges of variations in merchandising and pricing needs are manifest in The Home Depot and Best Buy, which are now heavily damaged brands in China.

Media reports have postured that China lacks the project-oriented customer that The Home Depot has targeted elsewhere. Julie Harris, Global Managing Director of research and forecasting firm WGSN, forcefully echoed this verdict in webzine Mashable. “People don’t have homes to invest in in China; homes are small, not spaces to invite your friends and display your wealth.” Selling online is not going to change these unfavorable demand patterns for The Home Depot.

For Best Buy, on the other hand, the problem is not lack of demand, but fierce local competition, especially from heavy-weights Gome and Suning. The latter has been consistently able to undercharge Best Buy. More problematic for Best Buy’s turn to e-commerce, their big Chinese rivals already boast strong e-retailing capabilities. As a Johnny-Come-Lately to the Chinese e-retail game, the time for Best Buy to gain substantial online market share may have past. The situation is quite different for big-name Western fashion retail brands. Jiao Tong’s Wei sums up the contrast.

“In consumer electronics, Chinese consumers are more price- and less brand-conscious, and will purchase cheaper local offerings; however, in fashion they want the real Western deal, and, unlike most electronic gadgets, acceptable local brands don’t exist,” Wei says.

Over the next decade, many of these consumers will be living in Western Chinese lower tier cities, where land-use issues make building new mega-malls difficult. This offers a huge new opportunity for Marks & Spencer, but exploiting it requires adopting an e-commerce strategy that maintains the brand’s integrity. In this regard, the British retailer may be better off focusing on selling through its dedicated Chinese site.

In Walmart’s case, it is well positioned to cash in on China’s e-commerce gold rush. But while it has beaten other MNC general merchandise retailers to the punch in partnering with Yihaodian, Walmart will find the digital ‘Shangri La’ a very crowded place. As Diaz noted, China e-commerce entry barriers for smaller, specialty product retailers are becoming less of an issue. These companies can now sell directly to consumers in China without having a physical presence in the country, as Macy’s has done.

MNC retail brands, even those facing setbacks, can make good on their China investments by shifting their focus to on¬line selling. But in the fast-changing and hyper-competitive world of Chinese e-commerce, these firms are unlikely to achieve the same brick-and-mortar presence as in their home markets. Still, a small slice of China’s $120-billion e-commerce pie is better than none at all.