Companies need to step up their service in China to satisfy the new sophisticated customer.

Lining up for a table at the Hai Di Lao Sichuan hotpot restaurant in Beijing is not such a bad experience–you get served tea and snacks and can even opt for a manicure while you wait–a welcome reprieve from other restaurants where creature comforts are an afterthought.

The latest battleground in the retail world of China is customer service. Competition is forcing companies from state banks and airlines to restaurants and auto showrooms to take greater care to attract and keep customers happy because Chinese consumers are becoming more savvy about, and insistent on, good service.

Up to the mid-1990s, poor service was expected. In a typical shopping interaction, a customer would approach a counter behind which were arranged goods guarded by an indifferent salesperson reading the newspaper, talking to another assistant or napping. A request to see a product was often rebuffed with a meiyou (not in stock), even when the product was evidently on the shelf.

That was the result of little competition, according to Ed Dean, founder of Shanghai-based customer service consultants group JETT. “For those businesses, it didn’t really matter if they sold anything, they weren’t going to go out of business,” he says.

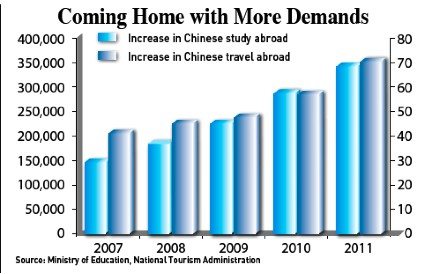

But in China’s increasingly competitive consumer markets, good service matters and businesses are fighting for the attention of increasingly wealthy Chinese consumers. Expectations are rising amongst the middle-class particularly given an ever-growing number of people returning from study or work overseas with a radically revised view of service.

The inroads multinational companies have made in the Chinese market are also impacting overall standards. Apple’s stores provide a stark contrast in China to a walk around a local computer mall.

“People are now aware of what they didn’t have before,” says Dean.

Old habits die hard however, and many companies are simply unable to live up to the new expectations of consumers. “Most of the working staff in China have only a very vague idea about what customer service means,” says 35-year-old Mihkray Rose, a Shanghai resident originally from Xinjiang. “They maintain traditional market thinking which simply means a sell and buy relationship.”

Chengdu native Jimi He is more blunt: “Either they don’t give a damn about the customers, or they promote their goods in the wrong way.”

Li Wei, Professor of Accounting and Finance at CKGSB, says that this gap between expectation and what is delivered is a big issue in China. “Consumer needs are rising every day but the development of customer service is not as fast,” he says.

Filling the Gap

The customer service gap is exacerbated by the changing characteristics of both consumers and products.

Benjamin Cavender of Shanghai-based China Market Research Group points out that the 18 to 35 age group is driving spending, and tending to be only children. They’re used to being doted upon, “so they are demanding a lot more from companies when they go to shop for products.”

In an increasingly competitive market, companies have an “incentive to provide better customer service,” says Li.

Dean agrees: “You need to care about repeat business and this comes from a good reputation. A good reputation comes from having a good brand and good service.”

The McKinsey consultancy group, in a recent report titled Building Brands in Emerging Markets, referred to the crucial impact of customer service in the retail decision-making process.

“The in-store experience is by far the biggest factor in finalizing emerging-market consumers’ flat-screen-TV purchase decisions, and Chinese consumers are almost two times more likely to switch brand preferences while shopping for fast-moving consumer goods than US consumers are,” the report says.

As China becomes richer, customers are often buying products for the first time. McKinsey pointed out that first-time buyers account for 60% of auto purchasers in China. With consumer electronics, between 30% and 40% of laptop purchases in China are made by first-time buyers, says the McKinsey report.

“They’re purchasing products they haven’t bought before and so they are expecting education (from sales staff) to go with that,” says Cavender.

It is not only tier-one and two markets that are seeking a better customer service experience, says Jeffrey Tan, research director at Starcom MediaVest and author of the firm’s Yangtze Study. In fact consumers in remote areas need more help in deciding what to buy: “Consumers need more guidance in lower tiers and so there is a more important role for shop keepers and sales people.”

Another emerging issue for customer service representatives is post-sale assistance.

CKGSB’s Li says that transactions for products like automobiles and computers, where follow-up care and maintenance are at play, aren’t necessarily done when the sale is made, and customer service has to extend to after-sales support. As Chinese consumers continue to increase their consumption of these high-value items, so must the attention to the service surrounding these purchases.

“I have seen many businesses in China succeed through better customer service,” says Jason Inch, author of China’s Economic Supertrends and founder of In China Corporate Training. “These include domestic Chinese companies such as Haier, with its after-sales service, and Hai Di Lao Hot Pot’s famous waiting area service.”

Middle-class consumers seem increasingly prepared to base their purchasing decisions on customer service.

“It directly decides if I would consider using their service or not the next time,” says Rose.

Such attitudes contrast starkly against past ones in China where price and function were the only considerations.

The Bumpy Path to Service

There are several challenges to delivering better customer service in China, but first and foremost is finding and training the staff.

Cavender says this is particularly clear with in-store sales. “It’s difficult to train them to really know the products–as they need some level of experience with them–and to know how to interest the customer,” he says. “It is also very difficult to teach someone to cross-sell. Most service staff aren’t able to suggest what will go well with, say, a suit because they haven’t been taught it or received that kind of service themselves. It’s something the customer in China absolutely wants but it is very difficult for them to get.”

One reason it is so difficult to find the right people is that service jobs are sometimes viewed negatively, with a subconscious belief amongst Chinese people that it is demeaning to serve.

Chinese parents prefer their children to work in a ‘more respectable’ environment, such as an office. Dean recounts an example of parents in Suzhou marching into a hotel where their daughter was employed and telling her that she was no longer to work there, but at an office job they had found for her.

Once the staff are hired, there is still the question of keeping them motivated to provide good

service.

CKGSB’s Li says ‘reciprocity’ can be problematic. In the hospitality industry of most mature markets, there is a ready-made prescription for dealing with difficult customers, one usually stemming from a ‘customer is always right’ philosophy. In China however, nasty customers can have a much graver impact on employee morale. When training, Dean said he encountered reluctance from hotel staff to even greet customers because of their lack of response.

The cultural concept of ‘losing face’ makes the rapport between staff and customers particularly crucial when Chinese consumers are purchasing high-value goods such as vehicles and computers, and doubly so for first-time buyers.

Li says it is important that customers feel like the company cares about them and they are given respect, particularly when things go wrong.

While the indifferent sales person has probably retired by now, stories of poor service are still rife. One Bank of China customer, who prefers to be unnamed, tells of having to fly from Guangzhou to Shanghai to get a replacement bankcard simply because his account was opened in Shanghai.

Banks in China are notoriously inefficient, a problem common to many of China’s state-owned enterprises, thereby holding back the average level of service in China, says Li.

For some Chinese companies, their very structure may be the cause of inefficiency and ineffective customer service. A global Accenture customer service survey shows that one key factor to gaining a rating of ‘satisfied’ from a customer is the ‘one-stop-shop’ factor. Many large stores in China take a fragmented approach to problem solving, where a simple refund can involve anywhere from two to five people up the command chain, leaving the customer less than satisfied.

Getting it Right

Some companies are overcoming the obstacle of cultural attitudes by going on the offensive, and making their work environment irresistible to would-be employees. This allows them to generate high morale, which is reflected in the way the customer is treated.

In an industry known for high turnover amongst staff, Element Fresh–a China-based restaurant chain–has over 300 people who have been with them for more than three years, and they have been ranked one of China’s Top Employers by the CRF Institute, a UK-based global human resources research organization, every year since 2009.

“Service 10 years ago was very basic, and mostly reactive, guests waving and calling ‘fuwuyuan’ (waiter),” says Frank Rasche, Managing Partner of Element Fresh. One of the ways they have overcome this and achieved staff retention is by building a strong team with a cohesive culture, “a team that stays together and develops.”

Rasche attributes the chain’s quick expansion in China’s major cities to their service approach. “We treat guests like friends,” says Rasche. “We encourage our team to interact with a friendly yet confident attitude. We are not asking our staff to be subservient.”

Rasche is one of many who agree that training is crucial to improving customer service. But it is also a big investment with only long-term payoffs, deterring many Chinese companies, says Cavender.

Every sector has a balance that must be struck in which competitive pricing and customer service complement one another, and lopsided attention to one over the other is not always the best approach. Too much stress on customer service, to the detriment of margins, is also something companies have to avoid.

Mark Ray, Director at the Shanghai branch of market research firm JLJ Group, points to Best Buy’s unsuccessful foray into China saying there was “an overemphasis on the importance of the custom experience, in an industry that demanded tight margins in order to compete.”

Before closing, Shanghai’s principal Best Buy location was across the street from the famed Pacific Digital Plaza, where every tech product under the sun is sold and haggling prices to half their original amount is commonplace. This was simply not a boutique market location.

In striking the balance, some businesses are incorporating training that gives their employees a peek into different markets with more developed service approaches, to compensate for a lack of first-hand service experience.

Jason Inch describes KFC’s entry into Beijing, where trainees watched recordings of their Hong Kong and Singapore operations to show staff the expected service. To further the understanding, Inch says role-play is effective in building empathy for the expectations of the customer. Videotaping interactions and then reviewing “helps them to improve attitude and see how they could have solved a problem in other ways,” says Inch.

The current lack of staff with first-hand experience of quality customer service is likely to be less and less of a problem in the future. With increasing numbers of college graduates entering the job market, there will be an increase of better-educated personnel in these jobs.

“We are going to get people filling these roles going forward who will have had some experience with these products and services, but it is going to be a gradual change,” says Cavender.

Regardless of the anticipated influx of educated personnel, nothing is a substitute for management acceptance of the concept of customer service.

“Only management buy-in is going to change the systemic issues in a company, so I think the challenge is first to change the processes, and then train for the new desired behavior,” says Inch.

Travel booking firm Ctrip uses a process of “six sigma” to standardize the travel service experience. Call monitoring is used to ensure consistent use and to create continual improvement. Ctrip’s emphasis on customer service has earned them a more than 40% share in all major segments of the OTA market, according to a 2011 China Internet Network Information Center survey.

Continual improvement is important, says JLJ Group’s Ray: “Those who have been successful will tell you that it is an ongoing process that never stops; with the most successful just as focused on the customer experience as with innovation. Think Apple.”

Another area where management buy-in helps is support for staff. Inch believes it’s important for staff to see how what they do impacts the company. and for them to be noticed provides initiative to offer good service. “So-called extrinsic motivators are very important for younger Chinese workers, who want individualized recognition,” he says.

In China, the next growth story will be the lower-tier cities. In these markets, the personal touch can be an even more effective weapon in gaining market share.

“They are not as exposed to information. They’re looking for people who can guide them and enrich them with knowledge,” says Starcom’s Jeffrey Tan.

(Image courtesy Flickr user Augapfel’s photostream)