Three erstwhile copycats innovate through trial and error, to fight the fierce war over online classifieds market

Three erstwhile copycats innovate through trial and error, to fight the fierce war over online classifieds market

A few years back Ren Jinglei, a university student interning at an IT company in Beijing, decided to buy a bicycle to ease his commute to the office. Like an increasing number of Chinese people, Ren prefers to do his shopping online and he promptly turned to the internet for help.

However, this time around the problem was a wee bit pricklier than usual: Ren wanted a second-hand bike–compared to a new bike, the odds of someone stealing it were low. But all the e-commerce sites like Taobao, Dangdang and 360buy.com deal with new products. “Taobao is great for shopping, but it doesn’t have second-hand options,” says Ren. “I figured that some other site must have them.” So Ren did the next best thing, and entered his query in Baidu, the most popular search engine in China.

The Baidu search results pointed him to Ganji.com, a site that markets itself with the slogan: “Ganji, we have everything.” It was smooth sailing from there on. Ren zeroed in on advertisements for second-hand bicycles available in Chaoyang District, where he worked–it would be easier to collect it from somewhere close to office. And when he finally found what he was looking for, he set up a meeting time with the owner. The next day Ren simply walked across to a subway station near his office, handed over RMB 320 to the owner and got his bike.

Ganji, as its slogan claims, has everything–if you are looking for a second-hand bike like Ren, the site will help you find one. If you are looking for an apartment to rent in a specific part of town, it will give you enough options to choose from. And if you want a boyfriend for that matter, Ganji will rustle up a list of potential beaus in a matter of seconds.

Ganji is the brainchild of 38-year-old Yang Haoyong, one of the many young entrepreneurs behind the vibrant start-up scene in Beijing’s Haidian district. After studying computer science at Yale University in the early 2000s, Yang moved to San Francisco and worked in technology companies such as Juniper Networks and co-founded Triomphe Networks. It was then that he became a big fan of Craigslist.com, a hugely popular classified advertising website in North America.

Craigslist, founded by San Francisco-based computer programmer Craig Newmark in 1995, is a trailblazer of sorts. While it started out as a listing service for Newmark’s friends (hence the curious name), Craigslist has grown to become the ninth-most trafficked site in theUS, according to web information company Alexa.com. It allows users to advertise online for sales, services, housing and jobs, among other things. Despite its popularity (it gets 50 million users in the US alone and 30 billion page views per month), the site doggedly sticks to its original simple formatting and eschews advertisements. Craigslist’s killer app? The fact that users across the 700-odd cities (US and elsewhere) it operates in can advertise for free. There are a few exceptions though–such as job advertisements in 18 US cities (at a nominal $25 per listing, except for San Francisco where it is $75), and apartment classifieds in New York ($10 per ad).

Time went by, and Silicon Valley’s infectious entrepreneurial energy rubbed off on Yang. As he toyed with possible start-up ideas, he thought of replicating the idea of Craigslist in China. So in 2005, Yang packed his bags and headed home. He borrowed $100,000 from his friends and set up Ganji.com.

At first, Ganji was simply what it set out to be–a Craigslist copycat. And the opportunity was huge too–the number of internet users in China was exploding. But Yang was not the only one to set sights on the opportunity–while no one has the exact number, it is rumored that in 2005, 2,000-3,000 Craigslist wannabes sprouted all across China in just three months. What would have been an empty space, was crowded from the first day on. And even though the size of the pie was growing, the number of companies that wanted to have a share of that pie was huge.

Yang’s fledgling company had to deal with competition from similar start-ups such as Zhantai and Renren, and also from the Big Boys of Chinese Internet–Sina, Sohu, Netease and Tencent–all of which launched their own versions of web classified sites. Competition was brutal. “The first 2-3 years were not about the business model or how big you can be, but about survival–and differentiation,” says Yang. To cut through the clutter, Ganji had to ensure that it was strategically focused on a few segments. “We chose to focus on one city (Beijing) and just two categories–‘housing’ and ‘for sale’,” says Yang. The idea was simple: get some experience of these categories, learn and then expand to other cities.

At the heart of Yang’s strategy is a careful segmentation of customers–and his value proposition of “local” and “life-related”. He segments potential customers for internet businesses into four categories–brand name customers which sit “at the top of the food chain” (like Coca-Cola and Nike), small-to-medium businesses (with 50-100 employees and typically customers of sites like Alibaba and Baidu), local small businesses (with 1-5 employees) and virtual goods companies. Ganji is strictly targeting the local small business segment. “They are flower stores, moving companies, laundries, housekeeping services, babysitters and plumbers–their service range is within 1-2 miles… and everybody uses that kind of service every day,” says Yang. “They account for the biggest segment in China–probably 10 million or so.”

Seven years have gone by, and the web classifieds industry has witnessed a shakeout. The 2,000-odd websites have been whittled down to only a handful. Data from iResearch, a Chinese internet research organization, shows that as of August 2012, only 26 classified websites were still active. Those that fell by the wayside include, somewhat surprisingly, high-flying serial entrepreneur Joseph Chen’s Renren (after the company went bust in 2007, Chen used the domain for the popular social networking service Renren.com). Tencent pulled the plug on its classified section. Some sites were acquired by bigger players–such as 263.com, a subsidiary of the internet company 263 Network Communication Co., which was snapped up by Ganji in 2011.

The biggest lesson from the shakeout was that a pure copy of Craigslist will just not work in China. A case in point is Zhantai, a once popular classified site that is almost defunct now. Zhantai had hoped to emulate Craigslist with an easy-to-use, advertisement-free classified website. It also shared many of Craigslist’s altruistic goals. When Craigslist was created, it had no competition and was able to slowly build its indispensable status. Zhantai, on the other hand, faced deep-pocketed competition that used advertisements to siphon off users. According to iResearch, Zhantai is now operating with a skeleton staff and unstable servers.

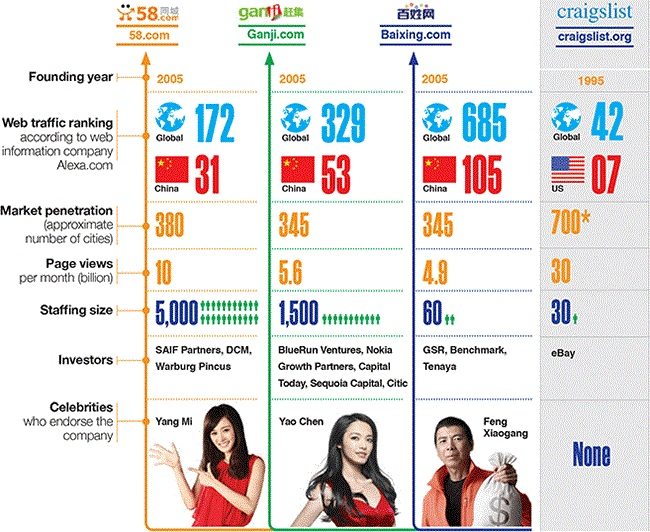

Out of the few survivors, 58.com, Baixing, and Yang’s Ganji lead the pack–and are growing at a frantic pace. Market leader 58.com has monthly page views of 10 billion, followed by Ganji’s 5.6 billion and Baixing’s 4.9 billion. All three are miles ahead of eDeng, number four in the pecking order, which has only 0.7 billion monthly page views. (In contrast, Craigslist, which has been around much longer, claims to get 30 billion page views per month.) iResearch’s most recent data also shows that 58.com’s average daily visit is 5.71 million, almost half of the total 12.7 million visits in classified websites, while Ganji has 3.86 million and Baixing has 3.21 million. (See ‘How they Stack Up’) While 58.com covers about 380 cities, Ganji and Baixing each has about 345. According to a Deloitte ranking and CEO survey titled ‘2011 Deloitte Technology Fast 50 China’, Ganji witnessed a revenue growth of 2,186% in the three years ending in 2011 and ranked fourth among the fastest growing companies in China.

Not a Copycat Anymore

Not a Copycat Anymore

Clearly, these companies have come a long way from the crazy days of 2005, when everyone jumped into the game armed with just two things: a cookie-cutter approach, and the aim to be China’s Craigslist. But climbing up the growth curve hasn’t been all that easy. Newmark created Craigslist in the Internet’s fledgling days and helped shape people’s relationships with the internet.

Chinese classified sites, on the other hand, entered a mature market where users were already familiar with the internet, and somewhat set in their ways. At this stage, the crucial battle was to attract users. Which is why, Ganji, as mentioned earlier, initially chose to focus its energies on just one city and two categories, learn, and then expand into other cities and categories. They made some mistakes along the way–such as a botched attempt at getting into the group buying segment–but learnt from the experience, and moved on.

Baixing has been trying to position itself as “a local community” where users can share and get different information in order to make their lives easier. As CEO Wang Jianshuo puts it, “There’s an awful lot of people out there who want to buy things, and many more who want to sell things. Linking them could change their lives for the better.” As for 58.com, they have decided to focus on housing, recruiting and dating services.

Even though these sites began as copycats of Craigslist, over time they have acquired nuances of their own that distinguish them from their original inspiration. Take for instance, Craigslist’s policy to shun advertisements. Chinese classified sites, on the other hand, rely heavily on advertising for revenue. Advertising revenue comes from third-party ads, and commission and advertising from property agencies with adverts for consumer goods a second source of cash.

Ganji’s Yang takes his inspiration from the concept of “freemium”, a business model in which services are provided free, but users need to pay for additional features and functionality. Globally many products and services–such as file-sharing service Dropbox and note-taking and archiving software Evernote–are based on the freemium model. “We are free to individuals but if you want to get premium service, you have to pay. For housing agents, moving companies, house-cleaning, the post is free but if you want better performance and better results, you pay,” says Yang. He adds that paid services account for less than 20% of their daily traffic.

Playing Matchmaker

Craigslist operates with a skeletal staff of 30-odd people–and it has always been this way. That’s because the majority of Craigslist’s transactions are user-to-user—interactions where individual users create listings for other individual users, without any interventions from Craigslist. The Chinese sites, on the other hand, are keen to play matchmaker.

Both Ganji and 58.com (Baixing is an exception) employ an army of salesmen and customer service staff. Out of Ganji’s total headcount of 1,500, 1,000-odd are sales personnel. Interestingly, many of Ganji’s sales people used to work for the newspaper classified business. “They already had (clients),” says CEO Yang. “We simply hired them and made them try a new medium.” While 58.com CEO Yao Jinbo refuses to disclose the numbers, out of the nearly 6,000 employees on its rolls, the company reportedly has 5,000 salesmen.

Ganji and 58.com are moving towards interactions where they help match businesses with local buyers. 58.com’s salespeople help connect the site’s users with merchants, a process that happens naturally in Craigslist. “The US is a service environment based on individuals,” says 58.com’s Yao. “But in China, the service environment is based on third parties–we provide a platform for middle and small local businesses. This is unique to China.”

But there’s also another reason why Chinese classified advertisement sites have so many employees. While Craigslist relies on its users to police themselves and administrators eventually step in to remove any listings that are flagged as inappropriate by users, both 58.com and Ganji employees scrutinize listings and ensure that they are indeed legitimate. Ganji employs editors who organize listings into specific categories and weed out fakes. (Baixing’s system to control fake information is much like Craigslist’s.)

New Revenue Opportunities

While classified advertising continues to be the mainstay for these sites, they have forayed into adjacent spaces as well. Ganji, for instance, experimented with group buying (and burnt its fingers because “competition was way too fierce”) and a short-term apartment rental channel, akin to Airbnb in the US. Through a sister site, mayi.com, Ganji offers options to people planning to stay in a city for more than three days. “By developing a forum to match landlords with potential tenants, Ganji hopes to target a more diverse client base and offer prices cheaper than hotels are able to,” explains Yang.

There are other revenue streams as well. Globally large-scale recruitment does not fall within the domain of classified advertising. In 2008, 58.com launched an experiment in this area–it signed a deal with Wal-Mart in which the retail giant agreed to hire 3,000 people per year via 58.com.

Another innovation in the Chinese classified websites market is the introduction of mobile phone apps. Yao says his firm has considered mobile as “one of our main focus areas”. From using mobile internet for news and entertainment, people are now also using their phones for shopping and other aspects of daily living. Qi Jianzhe, senior analyst at Analysys International, says that while mobile phone apps offer room for growth, they don’t deal with a key obstacle: a lack of accurate information. “The success of a mobile terminal depends on whether it can provide accurate information because the main feature of mobile applications is to provide the user with useful information from nearby,” Qi says. Let us suppose that a user is looking for an apartment within a one-mile radius and his mobile app throws up an option. However, he later discovers that the apartment is actually three miles away and this sours the experience. To compete in this market, user experience is the decisive factor.

From Craigslist to Taobao?

In early July 58.com CEO Yao Jinbo appeared on the reality TV recruiting program Fei Ni Mo Shu (loosely translated as “No One Else But You”) and offered a salary of RMB 400,000 plus stock options to hire a promising young e-commerce expert who had racked up sales of RMB 1.5 billion on a Taobao store. That set tongues wagging. “This is an obvious hint of 58.com’s plan of turning into an e-commerce platform,” says Huang Yuanpu, an analyst from iResearch.

Experts like Huang see classifieds sites gradually encroaching into the territory of e-commerce platforms, like Taobao and Alibaba. 58.com’s Yao agrees, saying that his site is already offering e-commerce in local services, but with a twist. “This is totally different from Taobao.com because they are into e-commerce of products. Our plan is to become powerful allies for local life for our users by helping them to get the information and save money,” he says. “We are changing from a pure information service platform to a platform for publishers, merchants and users.” Local business owners can continue to post product or service information on 58.com and make the transactions offline, or they can pay several thousands of RMB each year to have an online store on Wang Lin Tong (loosely translated as ‘internet communication for neighbors’), a corporate platform that 58.com created for its VIP customers to promote business. In the meantime, Yao is preparing to launch an online transaction platform like PayPal and Alibaba’s Alipay.

Huang doesn’t think that foraying into e-commerce is such a great idea. “For the classified ad websites, the expense is several times the revenue. Thus, each player faces the pressure of monetization. E-commerce is a helpless choice, because the competition in this area is already very fierce,” he says.

In for the Long Haul?

Anyone who rides the Beijing subway regularly or watches national television has probably seen–or heard–the advertisement for Ganji starring actress Yao Chen. She rides an animated donkey and yells, “Ganji la!” (“Let’s go to the market!”). Subway riders will also be familiar with another commercial in which TV actress Yang Mi shouts, “58, tong cheng!” (“58, we are in the same city!”). In the battle for users, Ganji and 58.com have both been splurging money left, right and center on staff and marketing. Chinese media has reported that 58.com and Ganji have both spent RMB 500 million and RMB 400 million respectively on advertising in 2011 alone. This is unsustainable in the long run, as the ad spends are higher than the revenues. TechWeb reported that 58.com’s total expenditure in 2011 reached $130 million (RMB 825 million) while it only raked $40 million (RMB 254 million) in revenues. iResearch’s Huang cautions against this game of outspending competitors to gain market share.

Analysts are also worried about the fact that many sites are still pretty much the same. Analysys International’s Qi has studied the strategies of Chinese classified sites. “I am not optimistic about the future of classified websites,” he says, “because I have not seen a breakthrough in the profit model of any classified websites.” He believes websites which focus on niches have a greater chance of succeeding. In each category, Ganji and 58.com will inevitably face competition from specialized players, such as dating website baihe.com or recruitment site 51job.com.

Willingness to pay for ads continues to be a concern. “From our survey, less than 10% of users are willing to pay for the information they get from the classified sites,” says iResearch’s Huang. “Chinese consumers still haven’t developed the habit of paying for information they get online.” Also since these sites mainly target low-end users, their propensity to pay for advertising is low and it’s hard for the sites to monetize their traffic.

While new revenue models for China’s classified sites are as yet unproven what is certain is that in the future, China’s classified websites will continue to plough a different path from Craigslist. Craigslist fan and Ganji boss Yang believes the websites’ fate is in the hands of hard-won users. “Even though you (might be) number one on PC, there might be players on mobile and social platforms which create better user experiences that can beat you,” Yang says. “Those are the things we need to think about in future.” But he remains optimistic. Ask him about future projections, and pat comes the reply: “We cover 100 million monthly users right now. In three years, we’ll cover 200-300 million.”

(Image on homepage courtesy: Flickr @ CarbonNYC. Lead image on page courtesy: Flickr @ Zetson)