Chinese startup Luckin Coffee is expanding at a breakneck pace. How will Starbucks and other coffee players respond? Starbucks had coffee lovers in China’s main cities wrapped up until Luckin arrived, but is the market big enough and growing fast enough for both and more coffee vendors?

In years to come, the opening of the Starbucks’ Reserve Roastery in Shanghai in December 2017 may be seen as the zenith of the Seattle-based coffee chain in China. It was the largest Starbucks in the world when it opened, and the constant line-ups of fans outside the door showed how business was booming in the Middle Kingdom.

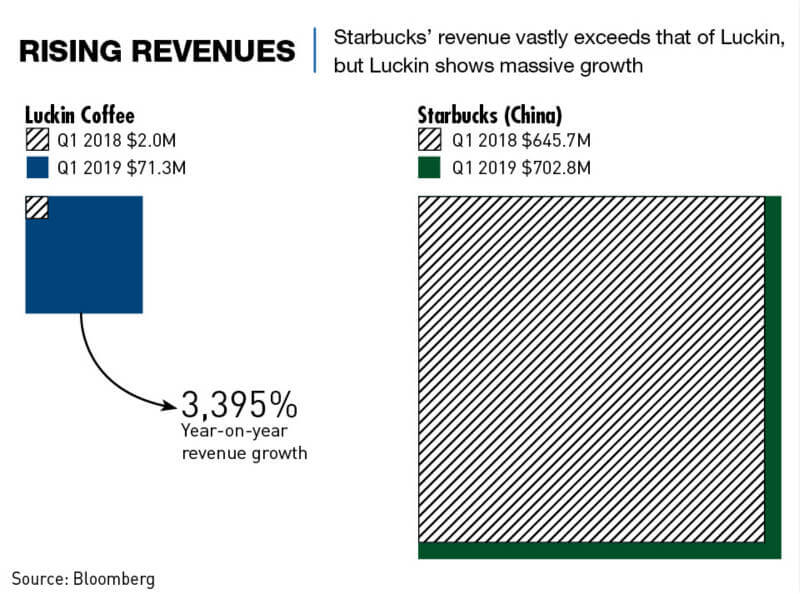

Back then, Luckin Coffee had just started, and few people predicted its meteoric rise. Luckin is the first Chinese challenger to Starbucks, which for nearly two decades was the only major coffee chain in China. In May 2019, Luckin raised $561 million with an initial public offering (IPO) on NASDAQ. It is now opening stores at a furious rate and aims to have more China outlets than Starbucks by the end of 2019.

Luckin is hoping to beat Starbucks with the sheer number of stores. In big cities such as Shanghai, many young Chinese cannot live without their daily cup of “joe,” but the average coffee consumption for the whole country is just six cups per person a year, which provides huge potential for future growth. Luckin’s prospectus says that Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan all have per capita coffee-consumption of over 200 cups per year.

“China still ranks low in coffee consumption,” says Michael Norris, strategy and research manager at AgencyChina, a China-focused marketing and sales agency. “Yet, total consumption grew at an average annual rate of 16% in the last decade, significantly outpacing the world average of 2%, according to the International Coffee Organization.”

Tea or coffee?

China’s coffee market was valued last year by Euromonitor at $5.8 billion, up from $2.7 billion in 2014. Luckin in its IPO statement cite figures from Frost and Sullivan, a business consulting firm, showing growth of coffee consumption from 4.4 billion cups in 2013 to 8.7 billion in 2018, with a projection of 15.5 billion by 2023.

Starbucks first entered the market in 1999 when it opened a store in Beijing. In 2017, the company controlled 80% of the coffee market and by April 2019, had 3,789 stores with plans to add 600 more within the year—a rate of one every 15 hours.

Luckin, in contrast, had nine stores in operation at the end of 2017, but is now opening on average one every 3.5 hours. By January 2019, it had 2,380 stores, about 60% of Starbucks’ total. The battle for who takes the lion’s share of future growth in the Chinese market is on, but numbers only tell part of the story.

Tea is the drink normally associated with China and it has been drunk here for over two thousand years. Dave Seminsky, founder of Shanghai-based Sumerian Coffee, estimates current tea consumption at around 95 cups a year per person. Many tea varieties, such as Longjing, are famed for their quality and supposed health benefits, but China is also among the top 20 coffee producers. Cultivation picked up in the late 1990s, mostly then for export. Coincidentally, it was at that time that companies started trying to sell the drink to Chinese consumers in the developed coastal cities.

Seminsky sees the expansion of the coffee business in China in three waves: mass brews, quality mass brews and finally boutique brews. “In the first wave, roasters focus on broad distribution over coffee quality and sourcing transparency,” he says, citing as examples instant coffees such as Maxwell House and canned coffees like UCC.

The chain gang

The second wave has been driven by Starbucks, along with some other foreign-based brands such as UK-based Costa and US-based Peet’s. This created a fad in China’s larger cities, especially among fashionable young people who yearn for a more internationalized way of life. Coffee is a proxy for that. Starbucks offers not just coffee but also an aura of coolness.

“They introduced artisanal elements to the industry, through increased quality, origin transparency and differentiating roasting styles,” says Seminsky.

In the early days after Starbucks’ initial launch, there were plenty of copycat brands using circular green logos and vaguely similar names. But few made a serious attempt at expanding the business to chain scale. One of the few, Mellower Coffee founded in 2011, only has 80 outlets.

Until Luckin appeared, the most concerted competition to Starbucks came from Costa Coffee. The British chain, now owned by Coca-Cola, aims to have 1,200 stores across China by 2022, which the parent company hopes will help offset falling demand for soda drinks.

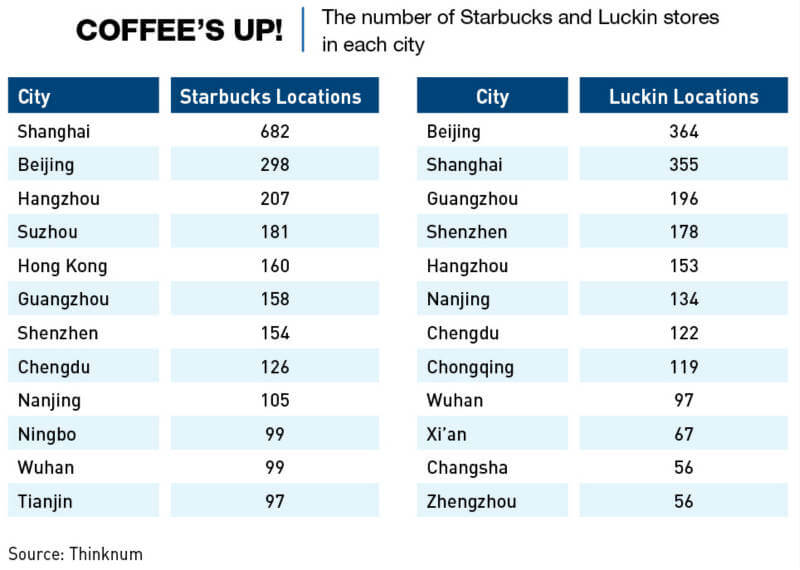

In China, Starbucks and Costa mainly operate in larger cities, whereas Luckin is branching out into smaller inland cities. Starbucks is dominant in Hangzhou, Shanghai and Suzhou, while Luckin has the edge in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

Starbucks coffees are more expensive, and it appears Luckin is using the money it raised to build market share by keeping prices low. In terms of quality of brew, some drinkers say the two are similar, while others see Starbucks quality as being ahead.

But there is a crucial difference between the two. Currently 95% of Luckin outlets operate on a takeout/delivery-only model with no seating available. Almost all Starbucks stores provide seating and table space. “Vibe-wise, Starbucks offers a place where you can relax, work or meet people,” says Shanghai-based marketing manager and coffee consumer Fu Siru.

Many Luckin stores are in office buildings. “That, in combination with the amount of money it’s been able to raise and throw at its expansion, puts it in a commanding position to take advantage of morning and afternoon caffeination occasions for office workers,” says Norris.

The problem for Luckin is that more sophisticated coffee consumers do not buy into the idea that the company is comparable to Starbucks. A survey by UBS of 1,000 coffee drinkers reported only a 23% overlap of customers with Starbucks. Dedicated Beijing coffee drinker Helen He buys two or three cups of coffee a day, usually from Starbucks, and has only tried Luckin once. “I’m not impressed,” she says.

“Luckin provides a similarly priced alternative to convenience store coffee that is billed as being better quality,” says Ben Cavender, principal at China Market Research Group. “The reality, though, is that Luckin’s coffee quality isn’t always better than what is on offer at convenience stores.”

“Luckin is certainly hurting Family Mart (a Japanese convenience chain with more han 1,430 stores) with a constant 50% off promotion and speedy service,” says Professor Diana Derval from DervalResearch. “In terms of a seated experience and appealing to other personas, the real competitors to watch are Taiwan-inspired bubble tea players like HeyTea.”

Luckin recently announced plans to create a standalone tea chain and seems more willing than Starbucks to compete in the wider beverage market. And most Chinese coffee drinkers certainly seem to still enjoy tea. “It really depends on who you hang out with,” says Allen Hua, based in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province. “I do both.” For him, Luckin “feels like a cheaper version of Starbucks. Other than that, they taste the same.”

Luckin to the future

Despite its market value of nearly $5 billion, Luckin is running at a loss. Figures filed for the IPO show operating expenses are nearly three times total revenues. More disturbingly, the costs of materials and store rental exceed total revenues. Starbucks, by comparison, has been profitable for more than a decade. Last year, its global gross profit was $4.5 billion on revenue of $24.7 billion.

Another major difference is that Luckins’ outlets are all cashless, with orders only accepted from their mobile phone app. “Luckin definitely shows how far ahead mobile wallets and digital wallets are in China compared to the rest of the world,” says Cavender.

Norris believes the Luckin model particularly appeals to lower-level white-collar workers earning less than RMB 15,000 ($2,117) a month. They want a certain lifestyle but find Starbucks coffees too expensive. Starbucks prices in China are often higher than in many Western markets.

“If Luckin can make inroads toward profitability, it has the opportunity to be the beneficiary from China’s emerging ‘java’ habit. The ultimate bull case for Luckin is it becomes the coffee of choice for white collar workers, especially those entry-level professionals who are earning RMB 4,000 ($560) to 8,000 a month,” he says.

The future landscape of the big coffee sellers in the China market will largely depend on how long it takes before Luckin can achieve profitability. The other question is how effectively Starbucks responds to this threat to its position as China’s king of coffee.

“What Luckin represents is a firm driving for significant scale over physical assets,” says Norris. “In winner-take-all or winner-take-most markets, the payoff for this ‘going big or go home’ approach is enough to justify the risk of an Ofo-like financial meltdown.”

Ofo is a rent-a-bike startup that spectacularly crashed. In some ways Luckin fits the model of private Chinese companies whose business models uses large amounts of debt to fund growth to become dominant in the market with little regard for profitability.

But other factors, including technology and big data, are impacting the way the battle is being fought, so profit on each cup of coffee is not Luckin’s only consideration.

“Luckin operates more like a technology startup than a traditional retail or F&B (food and beverage) company. I think its business model is indicative of what we see happening in China’s overall retail landscape, that is, fusing mobile wallets, on-demand services and traditional retail experiences,” adds Cavender.

“Luckin was the first to apply these technology trends to coffee on a large scale.” In its IPO prospectus the company used the word “technology” five times more often than “bean,” something not missed by more astute coffee drinkers and investors. “The company positioned itself as a ‘tech company,’ so I guess collecting consumer data is more important than serving quality coffee,” says Fu.

Smelling the coffee

As with countless other industries in China, coffee has to an extent become a proxy war between the tech giants, Alibaba and Tencent. Starbucks has teamed up with Alibaba on delivery to counter Luckin’s delivery model. Luckin has received support from Tencent. It is also a battle between more established Western ways of doing business and emerging Chinese models that allow for faster reactions to market shifts. “The fundamental question is whether morning and afternoon caffeination occasions are enough to sustain Luckin’s expanding footprint. Their latest quarterly earnings report suggests not,” says Norris.

Then there is the third wave of coffee—small independent quality coffee houses, a phenomenon already seen in China’s larger cities. These outlets amplify elements of the second coffee wave and add “emphasis on hand brewing methods, lighter roast profiles that introduce new exotic flavors and publishing of roasting dates to ensure freshness,” says Seminsky.

Some consumers such as Fu, educated in part by Starbucks, have graduated onto independents for their coffee fix. “Competing against Luckin and Starbucks is not something that keeps me up. Large chains lose the ability to quickly adapt, are slow to implement new offerings and lose control of the customer experience,” says Seminsky.

Ultimately, the market may be ripe enough for such a massive expansion that there will be no need for a winner-takes-all result. Between 1963 and 1970, Japan’s coffee consumption increased 3.2 times to 42 cups, and there is no reason to assume China won’t follow a similar trajectory, with some regional differences. Derval cautions, “In order to accurately estimate the coffee market potential, we need to talk about taste buds and provinces.”

Meanwhile, Starbucks released figures in April showing same-store sales in China increasing 3% year-on-year, indicating Luckin’s emergence has not had a big impact. Luckin, meanwhile, is looking to expand overseas after inking a deal with the Kuwait-based Americana Group to introduce outlets into the Middle East and India.

“Over the longer term, Luckin will struggle to make money,” says Cavender. “Companies like KFC are now competing aggressively on price and the value of their existing menus to make a strong value play that won’t be easy for Luckin to answer. Meanwhile Starbucks is struggling due to its price position in lower-tier markets but still has a strong entrenched position in the premium space.”

Luckin has benefited from being a Chinese brand at a time when consumer pride in “Chineseness” is increasing, as well as its broader product mix and tech-heavy approach to operations. But its main advantage is just the massive potential for growth in coffee sales. “The coffee market is huge for those able to adapt to the Chinese palate. Luckin coffee by its flexibility and customer-centricity is a strong contender in the battle with Starbucks, but the door is open for even better targeted brands,” says Derval.