China has introduced a new e-commerce law to tackle counterfeit goods and tax evasion, but how effective will the law be in better regulating the massive online consumer space?

Adidas’s Yeezy sneakers designed by rapper Kanye West have been among the world’s best-selling footwear since they were released in 2015, and a pair of Yeezy Boost 350 V2s retails for up to $1,000 on most e-commerce sites. But on Alibaba’s Taobao site, the world’s largest online marketplace, vendors offer the same pair of sneakers for as little as RMB 300 ($45).

That sounds too good to be true, and it is. They are counterfeits.

Chinese consumers aren’t fooled either. “Chinese consumers are among the savviest in the world when it comes to detecting fake goods—they’ve had a lot of exposure,” says Dean Arnold, managing director of Shanghai-based consultancy O2O Brand Protection. “They buy fake fashion items when they want the brand, but at a fraction of the real price.”

China’s e-commerce titans have robust takedown systems in place, but ultimately the burden has been on the authentic brands to report the offending listings. The brands lack the manpower to catch most of the counterfeiters, and also the legal machinery to counter the counterfeiting, which is not confined to Taobao—it is a feature of just about all Chinese online market platforms. WeChat, as a Chinese multi-purpose messaging and social media app that is often compared to WhatsApp, is also regularly used as a sales platform for counterfeit products.

“Selling inferior-quality products is the most pronounced illegal practice found on WeChat stores and live-streaming platforms,” Piao Xiaolin, a senior official at China’s Consumer Association, told Xinhua in a January interview.

This could all change dramatically with China’s new e-commerce law, which holds the e-commerce platform operators jointly liable with the individual sellers for infringements. Effective January 1 this year, the new law applies to e-commerce marketplaces like Taobao, WeChat, as well as any websites where goods are sold. For instance, if a fake Hermès bag was being sold on Taobao, under the new law both Taobao and the seller are liable and both could be punished.

The e-commerce law, which has been promulgated but not yet put into effect, stipulates that platform operators may be fined up to RMB 2 million ($291,000) for instance of intellectual property infringement.

The law also requires online sellers to obtain business licenses and pay taxes. For small overseas purchasing agents—more commonly known as daigou sellers in China—who import goods into the country through gray-market channels, the new law could spell trouble: for many their business model is only profitable because they don’t pay any taxes.

“The government doesn’t want to walk away from the tax revenue anymore,” says Ben Cavender, a director at the Shanghai-based China Market Research Group (CMR).

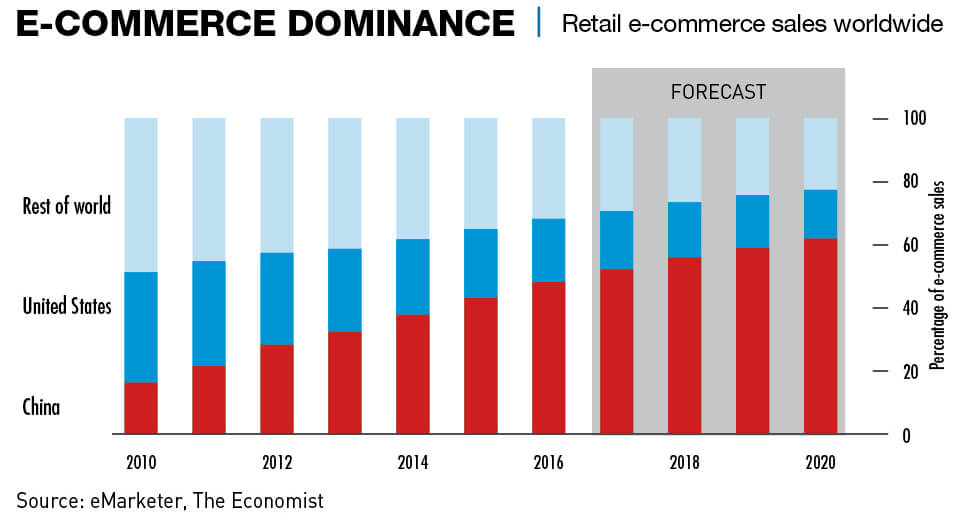

The e-commerce law comes as Beijing moves to assert greater control over the world’s largest online shopping markets, which were valued at $1.1 trillion in 2018, according to research firm Forrester. Forrester reckons online sales in China will grow at an 8.5% clip to reach $1.8 trillion in 2022, compared to the US e-commerce market, valued in 2018 at $713 billion.

Li Jiao, a counsel in the Amsterdam office of law firm Buren, describes the e-commerce law as a mini-constitution for China’s e-commerce regulatory system, establishing ground rules to ensure that the industry develops stably. Addressing criticism that the law lacks specificity, she says that China’s State Council is expected to enact further practical enforcement guidelines in due course.

“Chinese law usually establishes a concept first and then a framework by which the law is enforced,” she says. “The direction is clear: The industry will be subject to the same regulatory requirements as offline retail.”

The long arm of the law

The e-commerce law will arguably affect platform operators the most. The burden falls on them to keep the marketplaces on the straight and narrow. That in itself is a reasonable goal, but the sheer number of fake goods on sale in China makes combating the counterfeit trade a tough task.

Counterfeits appear just about anywhere that goods are sold online in China. The largest platforms have the most fakes, but they’re also best positioned to address the problem. They have deep pockets and advanced analytics capabilities. Alibaba, with a market capitalization of $442 billion, can afford to spend a bit of cash on anti-counterfeiting. So can Tencent (the owner of WeChat), which is valued at $418 billion.

The Chinese government is also concerned about fake products that affect human health because they pose real dangers to consumer safety.

In March 2017, as his company faced an onslaught of criticism about fake goods on its platforms, Alibaba founder Jack Ma called on China to get tough on counterfeiting. “We need to fight counterfeits the same way we fight drunk driving,” he said on his blog. “For example, if the penalty for even one fake product manufactured or sold was a seven-day prison sentence, the world would look very different, both in terms of intellectual property (IP) enforcement and food and drug safety, as well as our ability to foster innovation.”

It isn’t clear if the e-commerce law as it has been promulgated is what Ma had in mind, but it certainly places the onus on operators to police their platforms more aggressively. “They will have to put their money where their mouths are,” says Arnold of O2O Brand Protection. “The big operators are fully capable of proactively removing infringing listings, but until now they’ve never had financial reason to do so.”

The Daigou purchasing agents face a grimmer situation. Indeed, the e-commerce law strikes at the heart of their business model: private imports that can be sold at competitive prices only because they evade duties. In a February report, China’s state-run Global Times newspaper reported that Japanese duty-free retailers’ revenue fell over the Lunar New Year holiday in tandem with fewer purchases by Chinese customers. Retailers in Japan had been accustomed to daigou-powered shopping sprees.

Japanese brands have become so popular in China that thousands of Chinese residents in Japan are believed to be working as daigou merchants, Japan’s Nikkei Asian Review reported in March. But this era could be drawing to a close now that they are being forced to compete on a more level playing field with licensed importers.

Bigger daigou merchants are likely to register as companies, pay taxes and become legitimate businesses, while smaller ones will probably close shop, says CMR’s Cavender. “The lady who sells a small volume of merchandise through her WeChat group isn’t going to want to deal with the complicated paperwork and accept low margins.”

With that in mind, Chinese consumers may end up paying higher prices for imported goods in high demand, like luxury goods and nutrition supplements, he says. With fewer gray-market options, “it will be harder to get a good deal,” he says.

By the same token, Beijing is mindful of ensuring fair competition in the e-commerce market, notes Mark Tan, a partner at Taylor Wessing in Shanghai. “The law addresses the complaints of licensed importers—that daigou merchants have an unfair advantage because they don’t play by the rules,” he says.

Another group of operators affected by the law are overseas sellers without a physical presence in China. Before the law was enacted, they could sell goods to Chinese consumers from overseas without registering as a business in China or paying taxes there. Those days are apparently over.

The e-commerce law applies to all e-commerce business activities within China’s borders, therefore including the sale of products on a Chinese e-commerce platform by a foreign business, even if they do not have a Chinese entity. According to the American Chamber of Commerce, even the sale of products on a foreign website by a foreign entity to a consumer in China will likely also be considered to have occurred within China and therefore subject to the e-commerce law.

International law firm Harris Bricken highlights that it may be challenging for foreign companies, especially smaller businesses, to comply with these requirements. Already, some foreign stores that used to ship their products directly to China for their online sales have rather opted to open shops on large Chinese e-commerce platforms through a Chinese distributor or subsidiary. Others have pulled out of the Chinese market entirely.

There could also be a significant impact on the cross-border delivery model, says Taylor Wessing’s Tan. “The law gives Chinese authorities regulatory oversight over vendors outside of China selling to Chinese consumers,” he says. Those who fail to comply with the law could be subject to punitive measures, such as having their goods detained or their website blocked in China.

“Operating onshore [in China] will become more expensive, but will be necessary to mitigate risk,” he says.

The devil is in the implementation

E-commerce industry stakeholders are watching carefully to see how Beijing enforces the law. While they agree that Beijing intends for the law to create a more orderly e-commerce environment, it is unclear how effectively the law will be implemented.

“It’s a question of manpower and political will,” says Matthew Dresden, a partner and China expert at international law firm Harris Bricken. “We’ll see if it has teeth.”

For effective intellectual property protection, however, implementation at the local level is crucial. For instance, China’s big tech companies have been cooperating with local law enforcement for years and Alibaba regularly helps local authorities track counterfeiters by providing evidence of their illicit online activity. The e-commerce giant “has a very good takedown and verification system—it’s comprehensive,” says Buren’s Li.

But under the new law, the onus is on Chinese authorities to punish the offenders, and they have tendency to sometimes look the other way. For instance, in August 2017 authorities in Shaanxi Province apprehended counterfeiters infringing on the trademark of China’s Tsingtao Beer. Since the bogus beer were only valued at RMB 30,000 ($4,340), authorities decided it wasn’t worth their trouble to charge the suspects with a crime. Instead, they just made them empty all the bottles. In fact, they didn’t even confiscate the bottles, apparently suggesting they could be redeemed for cash at a glass recycling center.

“They [the suspects] could make much more money by refilling the bottles with more fake beer,” says O2O Brand Protection’s Arnold. He notes that fake goods sometimes make important contributions to local economies in China, and for that reason, authorities may be loath to put counterfeiters out of business.

Cases that do reach the courts face challenges of their own. “There are a huge number of cases involving counterfeiting, while China has a limited number of judges with deep knowledge of IP protection,” says Li. “It will take time for the judiciary to develop broader expertise in this area.”

One area where Chinese authorities are clearly enforcing the e-commerce law is the inspection of goods brought by individuals into China from overseas. It is precisely such strict custom checks that are discouraging daigou merchants from bringing goods into the country that could be construed as intended for commercial sale.

“Daigou [merchants] will have to be more careful about what they bring into China,” says CMR’s Cavender.

What the law will have the most trouble changing is entrenched Chinese consumer behavior. The interest in fake goods and in cheap parallel imports won’t disappear overnight, even if they become harder to find online.

One Chinese consumer, an experienced Shanghai-based financial services professional, told CKGSB Knowledge that she buys high-quality fake designer handbags that she uses outside of Shanghai—where she isn’t surrounded by her colleagues and friends. She uses the authentic handbags for work and social functions in Shanghai.

“A fake is 1/10 the price of a real one, and I can use the money I save to buy other things I want,” she says.

Some Chinese consumers don’t care if goods are fake or not, and they certainly don’t care if products they buy came to China legally with import duties paid, says Li. “They may not see trademark infringement as inherently wrong, or a reason to not buy a product. It’s related to education.”

If the law were to make the purchase of fake goods a crime, there would see a sharp decrease in demand for counterfeit and parallel import goods,“but the law doesn’t work that way,” she says.