As China’s state-owned enterprises enjoy a resurgence, private firms are growing anxious about their future

An explosive blog post by a self-styled financial veteran briefly knocked the wind out of the Chinese business community in September. In the piece, the author, Wu Xiaoping, argued that the country’s private firms should step aside and allow the state to increase its dominance of the economy.

The private sector has “basically fulfilled its task of assisting the state-owned economy in achieving its rapid development,” Wu wrote. “China’s private sector should not blindly expand.”

The article went viral on social media, sparking a storm of criticism from entrepreneurs, as well as support from left-wing commenters. When China’s online censors failed to step in and stop the debate, this was interpreted by many as an implicit government endorsement of Wu’s views, sparking more panicked speculation among businesspeople and investors.

Under normal circumstances, a blog by an obscure middle manager at a state-run investment firm would never garner so much attention. But Wu’s post touched a nerve. These are tough times for private firms, which have borne the brunt of China’s economic slowdown, as well as a series of government policies designed to clean up the environment and reduce risk in the financial sector.

In October, CKGSB’s Business Conditions Index (BCI), which tracks sentiment among small- and medium-sized enterprises, fell to 41.4. This is the lowest reading ever recorded since the monthly survey began in 2011.

There is a creeping fear among executives that the adverse operating conditions they are facing are a sign that the health of the private sector is no longer Beijing’s top priority. The saying “the state advances, the private sector retreats” (guo jin min tui) has again resurfaced in public debates.

The State Strikes Back

Mixed messages on the role of the private sector have been a common theme since Xi Jinping became head of the ruling party and president. When he assumed office in 2012, many expected Xi’s new administration to introduce sweeping market reforms.

At a key summit the following year, party leaders appeared to fulfill this expectation by, for the first time, stating that the market should play a “decisive role” in the economy. However, they also affirmed that the state should remain “dominant.”

A 2015 blueprint for reforming debt-ridden state-owned enterprises (SOEs) sent similar signals. The policy aimed at making SOEs more competitive, while also reinforcing their position as a pillar of domestic stability.

Crucial to the SOE reform has been “mixed-ownership reform,” which has seen Beijing coax leading private companies to invest large sums to take minority stakes in state conglomerates. Between 2013 and 2017, the private sector invested RMB 1.6 trillion ($233 billion) in SOEs, covering fields including civil aviation, defense, energy and telecommunications.

The policy was designed to make SOEs more dynamic through an injection of entrepreneurial know-how, but the reality has looked more like an enormous wealth transfer from private to public sector, with little visible effect.

“There have been few examples of investments through mixed-ownership reform that have led to anything other than just a mixing-up of capital,” says Thomas Gatley, China Corporate Analyst at Gavekal Research. “There’s not a lot of appetite for plowing a bunch of funds into a firm where that private money gains no control over management and can’t drive any increased efficiency.”

Other reforms have also strengthened the state sector at the expense of private firms. In the northeastern Rust Belt, China’s antipollution campaign has led to thousands of smaller private producers being shut down, handing greater market share to the large SOEs. The state’s share of national steel capacity increased from 60% to 67% just last year, while the government now controls 80% of coal, up from 45% in 2010.

This resurgence of the state sector, particularly in industry, appears to be the result of an intentional policy by Beijing. Xi himself has described the goal of SOE reform as being making SOEs “bigger, better and stronger.”

According to Lin Jiang, Professor of Economics at Sun Yat-sen University, Beijing has been happy for the state sector to expand because it views SOEs as crucial to meeting the government’s policy goals.

“SOEs are the main support to the Belt and Road Initiative and are the main sources of fiscal revenue for the central government,” says Lin. “The Made in China 2025 plan also relies on SOEs because they control most of the science and technology resources and expertise.”

Private Struggles

The picture has darkened for the private sector since the start of 2018, as firms across the economy have started to struggle.

In August, the year-on-year growth of private firms’ assets had fallen to just 2.3%, compared to 2.5% growth for SOEs, according to Shan Guo, an analyst at Rhodium Group focusing on SOE reform. This is the first time that SOEs’ assets have been growing faster than those of private firms since the 1990s.

The private sector has been disproportionately hit by Beijing’s deleveraging drive, launched in 2017 to reduce risk in the financial system. The crackdown on shadow banking has cut off a vital source of funding for firms, as banks prefer to lend to SOEs, regarding them as lower-risk.

Starved of funds, many private firms have been pushed into riskier borrowing practices, raising capital through stocks, bonds or by pledging equities as collateral for bank loans. These practices came back to bite businesses this year, as China’s stock market began to struggle. Driven by worries over the impact of the US-China trade war and the deleveraging drive, the Shanghai bourse fell more than 25% during the first 10 months of the year.

With their stock pledged as collateral for loans, a number of private firms were forced into defaults. And many of these firms ended up in the arms of the state. More than 30 companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges sold controlling stakes to central, provincial or city-level governments in October alone, raising concerns about a wave of “re-nationalization.”

It was in this context, with the stock market taking a battering and a growing number of private firms going bust, that fears of a return to state control such as that described by Wu Xiaoping spread. But Wu’s post also tapped into another vein of suspicion among entrepreneurs: that Beijing would increase the dominance of SOEs in order to ride out a messy trade war with the United States. Wu appears to make this argument explicitly in his article.

“If we fail to concentrate the power of the state but instead allow the market to dictate and move toward a path of complete economic liberalization, … the results we have gained could gradually be lost,” he wrote.

As Andrew Polk, the co-founder of consultancy Trivium China, explains, Beijing has often turned to SOEs in times of economic turbulence. They can be trusted to steer clear of mass layoffs in times of trouble and to faithfully execute Beijing’s policy goals.

“SOEs are a buffer,” says Polk. “They help cushion the economy on the way down, but they also don’t operate as efficiently as they normally would on the way up, and so they function to some extent as a social lever. It’s much easier to keep people employed at SOEs during the down-cycle.”

Official Denials

Beijing appeared to wake up to the severity of the situation in September. That month not only saw the furor over Wu’s post; it also coincided with the US’s move to slap tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese imports. The same month, the CKGSB BCI plunged more than 10 points to 41.9, its lowest ever reading at the time.

During the fall, senior officials almost daily tried to reassure businesses of the government’s support for the private sector. “Any words and practices that negate and weaken the private economy are wrong,” Xi Jinping said in a letter to private entrepreneurs in October.

At a symposium the following month, the president doubled down on his “unswerving” support for private firms, and presented a six-point list of free-market measures, including promises to level the playing field and create an “environment of fair play.”

The government has also cut taxes, encouraged banks to lend to SMEs, introduced tax payment deferments and set up credit enhancement funds, says Polk. Meanwhile, the People’s Bank of China has earmarked RMB 10 billion ($1.45 billion) for private sector bond issuance in order to sooth financing difficulties for the increasingly credit-starved sector.

It is easy to see why Beijing is concerned. Despite the recent growth of the state sector, private enterprise remains vital to the health of the economy. The private sector employs 340 million people and creates 90% of new jobs, according to the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce.

The measures outlined so far have at least done enough to reassure entrepreneurs that Beijing wants to see a thriving private sector. “The advancement of state firms has been largely an unintended consequence of China’s broader deleveraging campaign, rather than a deliberate statist intention of policy,” says Guo, of Rhodium Group.

However, it is still unclear whether the moves will be enough. “I think people see the government is trying, but aren’t quite sure if the measures are going to be successful,” says Polk. “There’s just too much uncertainty to say that it has fundamentally improved sentiment.”

Despite Beijing’s talk of “level playing fields,” it is clear that systemic biases remain in the financial system that favor SOEs. As Guo emphasizes, state firms also appear consistently to be “hurt less” by environmental campaigns.

And some doubts remain over Beijing’s attitude toward the private sector. Polk from Trivium China points out that even as the government moves to provide relief to struggling firms, the party is inserting itself more actively into private businesses to ensure they uphold party goals.

Even some official statements in support of the private sector have appeared to confirm, rather than assuage, suspicions that Beijing is deliberately strengthening the role of the state. In a news conference on October 19, Vice Premier Liu He rebuked critics of private enterprise, but he also sketched a vision for an economy effectively split between an SOE-led industrial sector and a consumer sector populated by private companies.

“SOEs are mostly in the upper stream of the industrial chain, playing a leading role in the fields of basic industries and heavy manufacturing,” Liu told reporters. “Private enterprises are increasingly providing manufactured products, especially consumer goods. These two are highly complementary, cooperative and mutually supportive. In the future, the Chinese economy will continue to improve in this direction and move toward high-quality development.”

Such a frank statement in favor of more state control may come as a shock to many. But, then again, the idea that China is steadily moving toward an American-style market economy has largely been a Western one.

“It’s difficult to argue that the Chinese leadership ever wanted a completely free, market-driven economy,” says Guo.

Chinese policies have long emphasized state dominance over “key” and “pillar” industries. The problem for private firms, as Guo notes, is that the definition of what entails a “key” industry is frequently redefined.

“There hasn’t necessarily been a philosophical change in Beijing’s view of state versus private sectors in the economy,” says Leyton Nelson, a senior research analyst at China Beige Book, an independent data analysis firm. “The government is not looking to drive the private sector out of existence. They’re looking to keep economic stability. Given the control that the state exerts over SOEs, they’re the easiest way to do that.”

“China will never abandon its state companies,” says Cheong Kee Cheok, co-author of China’s State Enterprises: Changing Role in a Rapidly Transforming Economy. “At the same time, the state recognizes the dynamism of private entrepreneurs, especially in high-tech sectors.”

The Red-brick Road

Whatever Beijing’s reasons, it seems clear that the state sector will remain large, and may even continue growing, for the foreseeable future. This could have consequences for economic growth.

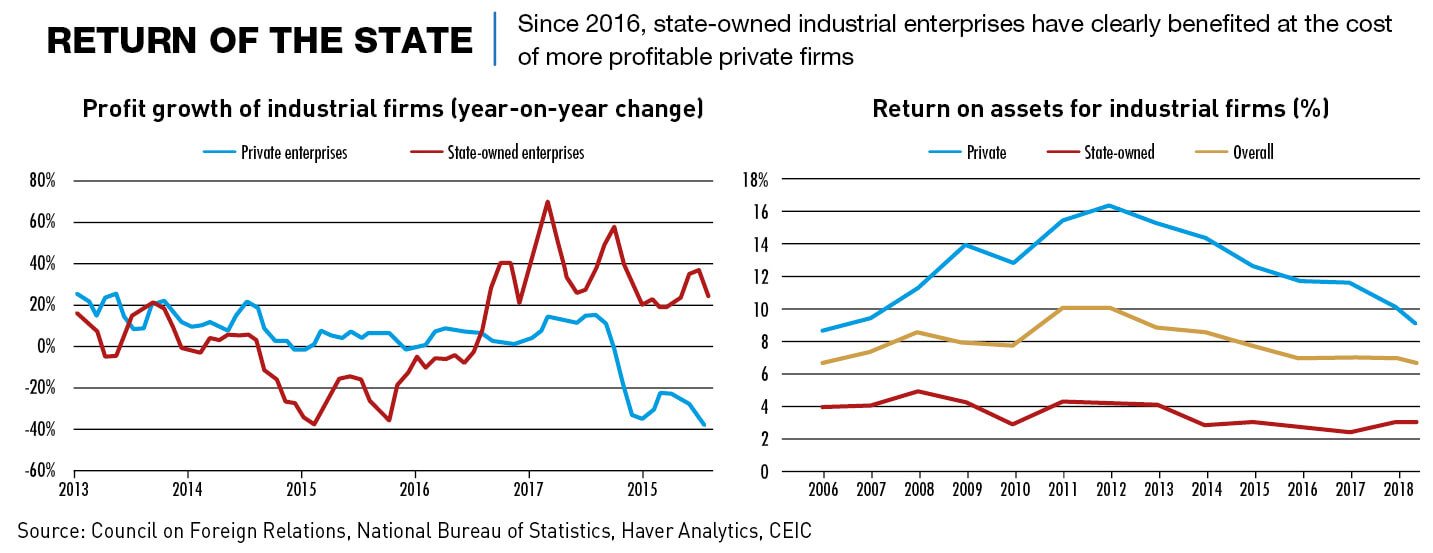

The effects of prioritizing the needs of SOEs can be seen in the industrial sector. Less competition from private firms has helped boost SOEs’ profits significantly since 2016. This is helping state firms pay off their enormous debts, which have risen to an astronomical $16.5 trillion, according to Ministry of Finance data. But the cost has been a decrease in productivity in the industrial sector, as SOEs generate less than half the return on assets achieved by private firms.

“The economic slowdown is a stark illustration of how Beijing cannot rely on SOEs alone to juice economic growth,” says Nelson. “Policymakers are not blind to this reality.”

Continuing to favor SOEs could also have consequences internationally. In November, the European Union, Japan and the United States jointly submitted a package of proposed reforms to the World Trade Organization that would strengthen rules designed to prevent states from handing out large subsidies to firms. The target was China’s hand-outs to state-owned companies.

China can block these reforms if it chooses. But to do so would be to abandon its adopted stance as defender of the global trading system. Instead, Beijing would be forced to isolate itself as the lone defender of a state-directed model.

It is too early to judge how Beijing will respond. But there are tentative signs that it is starting to address some of its partners’ concerns. In December, the central government appeared to step up plans to deal with the large number of loss-making “zombie” SOEs.

Local officials were handed a three-month deadline to submit a list of “zombie” firms in their area. They will then have to wind up or restructure these enterprises by 2020. Of course, this may simply lead to a wave of mergers, producing a smaller group of very large SOEs. But if these firms are viable corporate entities, it will at least be a step forward.

And in the long term, Beijing is likely to allow the private sector to take the lead in most downstream industries, particularly those related to technology.

“As China moves up the value chain through technological upgrading, the role of the private sector will expand,” says Cheong. “The government recognizes that it cannot keep pace with these new technological innovations and has shifted strategy to supporting high-tech startups.”