Gu Anzhong looks wistful as he stares at a sleek BMW sedan at China’s first-ever import expo in Shanghai. The 52-year old management consultant had pined for the same model—with a price approaching RMB 1 million ($144,000)—as a second car to go with the purchase of a new villa on the outskirts of Shanghai, but rising bills scotched the plan.

“Cash flow is tighter since my family bought our second home. Two mortgages mean we have to be more careful,” says Gu. “It’s fine. Frugality never hurt anybody.”

Gu is hardly alone when it comes to watching his spending. Across the country, the talk is about cutting back in big ways and small—from cooking at home instead of eating out, to getting around by bicycle rather than taxis.

At a busy KFC restaurant near the expo, for instance, Yang Jianhong says he used to eat fast food several times a week, but this year has cut down to once or twice per month. “I pack my own lunch now to save money, like many of my colleagues,” says the 28-year old graphics designer.

After years of enjoying the fruits of a booming economy and sharply rising disposable income, life for many of China’s higher earners is getting harder. Amid mounting debt levels and economic headwinds, urban middle-class consumers like Gu and Yang have responded by scaling back their discretionary spending and reducing luxury purchases—an emerging phenomenon known as the “consumption downgrade.”

Social media chatter over this pullback began in the summer. “This generation of young Chinese, brace for the bitter days ahead,” Beijing-based blogger Ma Ning wrote in a widely read social media post in August. Ma told her followers that “things have changed” since the boom times and warned them to brace for a diet of pickled vegetables and cheap erguotou liquor, a white liquor made from sorghum.

Recent strong performances by budget food companies appeared to support Ma’s theory. Instant noodle maker Tingyi Holding reported an 8.5% annual increase in revenues for the first half of 2018, following years of stagnation. Tingyi’s stock price in Hong Kong doubled from a year ago to nearly $48 per share in July, before falling back to $28 in December. Shares in Beijing Shunxin Agriculture, an erguotou distiller, have soared by 82%.

Others have pointed to the phenomenal success of Pinduoduo, a social e-commerce app that offers group discounts on cheap, sometimes low-quality goods and groceries. The 3-year-old company, which raised $1.6 billion in a New York listing over the summer, reported merchandise sales of RMB 344.8 billion ($50.4 billion) in Q3 2018, not far from the RMB 394.8 billion of e-commerce giant JD.com.

The newfound frugality of middle-class spenders like Gu and Yang may be good for their wallets, but it is an unwelcome development for Beijing. Talk of a consumption downgrade has touched a nerve with authorities, who have long touted consumer demand for higher-quality, higher-priced goods as a key growth driver for the world’s second biggest economy.

With consumption now contributing more than two-thirds of annual output growth, the worry is that reduced consumer spending could thwart Beijing’s ability to shield the economy from the US trade war and prop up a battered stock market.

The Squeezed Middle

Recent economic data suggests that consumer spending is indeed slowing. Retail sales growth unexpectedly dipped from September to 8.6% year-on-year in October, the slowest pace since May and well behind last year’s full-year growth of 10.4%. Total vehicle sales—a pillar of consumerism in China—dropped 11.7% year-on-year in October to 2.38 million units, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. This is a dramatic reversal for a sector accustomed to double-digit growth.

Consumers are tightening purse strings for a number of reasons, according to Wang Dan, a consumer analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in Beijing. She attributes the primary cause to rising property prices, which have pinched disposable incomes for those living in first- and second-tier cities. “Because mortgages are picking up so much, household savings and consumption have been squeezed for other durable goods, like high-end cars,” says Wang.

Gu, the management consultant, concurs. Mortgage payments for his two homes have now topped RMB 80,000 ($11,600) per month. This enormous sum has not only forced him to park the purchase of the BMW, but also led to the cancellation of a planned summer vacation to the United States.

Prohibitively expensive property prices mean many people rent, but they have also been buffeted by a dramatic rise in rates since the start of the summer. Rents in China’s major cities have soared, with prices in Beijing up by as much as 22% year-on-year in July.

A downturn in China’s financial markets has also hit the pockets of consumers. Chinese stocks have been among the world’s worst performers this year, with the benchmark CSI 300 Index tumbling more than 20% between January and late November. Financial pain from the equities slump has been compounded by a collapse in peer-to-peer lending platforms and falling returns on wealth management products, which were favored by many white-collar workers as places to park their savings.

Yan Danmai, a 36-year old insurance broker in Shanghai’s commercial district of Xujiahui, says her finances took a blow when one defaulted peer-to-peer platform ran away with her six-figure RMB investment and another postponed its repayment. Without the help of high-yielding investments, Yan says she is now wholly dependent on her after-tax salary of RMB 22,000 for paying bills that include an expensive mortgage.

In other cases, people have cut back because of worries about the overall economic outlook and the potential implications for their jobs and income. Consumer confidence has been beset by slowing growth, a weaker currency, mounting trade tensions with the US and the withering stock market. And rising costs for food and energy have also prompted some consumers to seek to economize on their daily spending.

The Full Picture

But not all Chinese are scaling back. In smaller cities and the countryside, where cost-of-living pressures are lower, people are still upgrading lifestyles that are unrecognizable from a decade ago.

Lower-income groups, including rural residents and migrant workers, are prospering thanks to wages rising faster than those in the big cities. Real median disposable income for these groups grew by 8.4% year-on-year in the first half of 2018, accelerating from 7.0% in the same period of 2017, according to the EIU. Higher incomes, combined with property prices that remain relatively low, has strengthened the purchasing power of these residents.

Even among urban dwellers, the picture is nuanced. The wealthiest consumers are relatively insulated from any slowdown, while “for the younger generation—let’s say anyone who’s not married—their ability to consume is definitely much higher than any other generation,” says Bo Zhuang, Chief China Economist at TS Lombard.

“In western countries, young people borrow from credit cards. In China, it’s online financial platforms. They just borrow and spend as much as they can,” adds Bo.

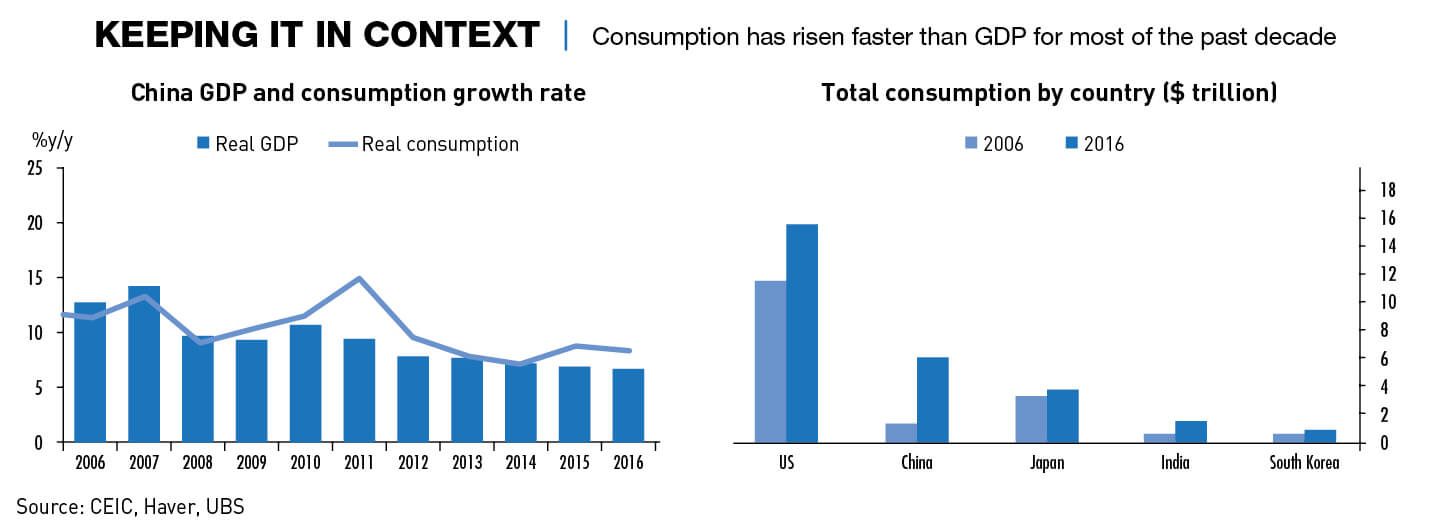

It is also important to keep things in context, points out Andy Rothman, an investment strategist at investment fund Matthews Asia. Consumption has been rising faster than gross domestic product (GDP) for years and is continuing to rise, just not as fast as before. Final consumption spending—which includes government expenditure—accounted for 78% of China’s GDP growth in the first three quarters of 2018, up from less than 50% in 2013, according to official statistics.

Certain categories and sectors continue to grow healthily. Wang from the EIU singled out insurance along with other finance-related services—even maligned wealth management products are enjoying a rebound. Upmarket household appliances have shrugged off the malaise affecting the property market so far, with premium-priced vacuums, hair dryers and air conditioners still proving popular.

In other sectors, the slowdown in spending can partly be explained by changes in consumer tastes, as much as issues in the wider economy. Rothman argues that consumers in China are undergoing the same shift in spending patterns that their counterparts in South Korea and Japan did 20 years ago.

“You’ve seen shifts away from luxury brands that are ostentatious to more low-key brands,” Rothman says. “And there’s been a shift toward more experiential stuff, whether it’s travel or services or education for the kids, as opposed to buying more stuff to put in the closet.”

In the auto market, whose spluttering sales are held up as a sign of a wider economic cooling, there are also issues specific to take into account. Sales have been weak this year in part due to customers rushing to buy cars in 2017, before tax breaks for certain vehicles were rolled back. In recent months, would-be car buyers have held off purchases amid speculation the government will slash taxes again to revive growth.

And while new car sales have been weak, Bo from TS Lombard points out that the used car market is booming with growth of 13% year-on-year in the first half of 2018. This indicates fundamental demand remains strong. “People still need cars. It’s just that they don’t want to buy firsthand cars because secondhand cars are cheaper,” he says.

Some commentators wonder if the reason why the consumption downgrade narrative has drawn so much attention is because it mainly involves the urban middle class, which exerts an outsize media influence “The consumption slowdown is most concentrated among middle-class consumers, and they’re the noisiest,” agrees Wang.

Rothman believes the fuss is simply part of a long-running trend to play up China’s weaknesses. “I think there is a tendency to look for the negative story in China by a lot of commentators,” he says.

Media coverage of this year’s Singles’ Day, an e-commerce festival that takes place on November 11, serves as a good example of this trend, according to Rothman. Alibaba raked in 27% more revenue from the flagship sales extravaganza than in 2017, but some reports were quick to point out this represented a slowdown from 39% growth in 2017.

“Singles’ Day for Alibaba is seven times larger in value than Amazon Prime Day, and so to expect the year-over-year growth rate to continue accelerating forever is totally unrealistic,” says Rothman.

Shoring up Consumption

For now, China’s economy continues to chug along at a reasonable pace. Driving consumption remains a top priority, as evidenced by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s pledge at the recent import expo in Shanghai to promote imports and demand for pricier, better-quality premium products. The goal is to import $40 trillion in combined goods and services over the next 15 years, or an annual average of $2.67 trillion—up from last year’s $2.3 trillion.

Beijing has also moved to ensure China remains the world’s best consumer story. From the start of 2019, Chinese shoppers will be able to spend 30% more on tax-free online purchases from overseas every year. The higher quota follows the country’s first income tax cuts in seven years, which hiked the salary threshold for paying income tax by more than 40%, to RMB 5,000 ($725) per month.

Consumers and analysts are divided on the tax cuts’ effectiveness. Bo says the higher income tax threshold and associated deductions—which allow Chinese taxpayers to deduct expenses such as mortgage interest and children’s education for the first time—will stabilize consumption and retail sales. “It’s quite likely they will have a significant impact,” he says.

But opinions on the ground are different. Yan, the insurance broker, claims the new tax code will only give her an extra RMB 600 per month. “It won’t make a difference to my disposable income because I have to put it toward my rising mortgage,” she says.

One option for the government that could provide a shot in the arm for consumption would be subsidizing purchases of certain goods. This happened in 2009-2012 with a massive subsidy program to boost rural sales of home appliances. But a new scheme could be fiscally unfeasible, as it would need to be targeted at urban dwellers and big-ticket items, such as cars.

Alternatively, the government could simply wait. While the consensus is that consumer sentiment will remain weak in 2019, Bo says that Chinese consumers have historically reined in their traditional spending patterns for 12-18 months at most before loosening the purse strings again.

“Once they have reduced their daily consumption, it doesn’t last long,” says Bo. “By the end of next year, they will start to forget about the higher housing prices, higher rental prices or whatever. They will get out and continue to spend.”

The wider question is how sustainable this spending is. After decades of thrift and saving, Chinese households are now taking on debt at an alarming rate. The national household debt-to-GDP ratio reached a record high of 49% at the end of 2017, up from 40% two years earlier.

Although household debt levels remain lower than in developed countries, the rapid buildup has observers worried as the cost of servicing loans could drag on long-term consumer spending and growth. “The increasing leverage among Chinese households is definitely a warning sign,” says Bo.

With Japan and South Korea, rising household debt stopped benefiting the economy when its ratio to GDP exceeded 60%, according to Bo. At the rate households are borrowing, China could hit this level as soon as mid-2020. When that moment arrives, it will take much deeper reforms than e-commerce tax cuts to get the economy back on track.