The Belt and Road Initiative has run into trouble this year as rising debt burdens weigh down China’s partners. Beijing has reacted by launching a range of reforms that will significantly change the nature and scope of the initiative

What a difference a year makes. Last summer, there was a sense of unstoppable momentum behind the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s trillion-dollar plan to build a network of infrastructure connecting Africa, Asia and Europe.

When China hosted its 2017 Belt and Road Forum, 29 heads of state and delegations from another 100 countries traveled to Beijing, hoping to cash in on what President Xi Jinping described as the “project of the century.”

This year the landscape, at least from the media’s perspective, looks dramatically different, as even China’s closest partners make more cautious noises about the BRI. Some have even suggested that the initiative is not a road to riches, but a “debt trap” set by China to gain influence and seize strategic assets from smaller nations.

In May, China skeptic Mahathir Mohamad won power in Malaysia in a shock election victory over Beijing ally Najib Razak. Within months, the new prime minister nixed $23 billion worth of BRI projects, warning of the dangers of a “new form of colonialism.”

Recent elections in Pakistan and the Maldives followed a similar pattern, with opposition leaders Imran Khan and Ibrahim Mohamed Solih ousting China-friendly incumbents. Khan’s government has already sought to renegotiate loans for billions of dollars’ worth of projects with Beijing.

A chorus of Western criticism has added to the sense of crisis, with figures including Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson all warning of the dangers of China’s lending practices.

As the fifth anniversary of the BRI approached, there was speculation that Beijing might quietly dial back the initiative. But in August, President Xi made clear in a high-profile speech at the Great Hall of the People that the policy remained central to his administration.

In the wake of the speech, the media narrative has become one of confrontation between Western critics and a defiant Beijing. But this assessment may prove wide of the mark. In fact, China is aware of the risks building over debt and has already initiated reforms designed to set the Belt and Road on a more sustainable path.

Debt Debate

Concerns over debt sustainability were always going to be baked into BRI given the nature and scale of the projects it encompasses.

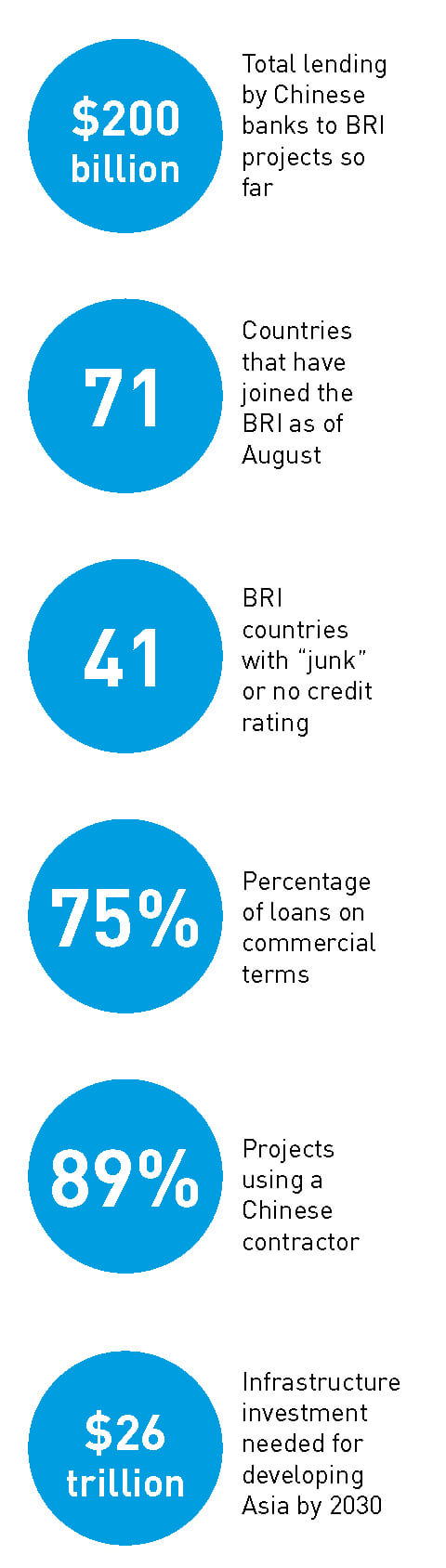

Chinese banks have loaned more than $200 billion for 2,600 projects since 2013, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission estimated earlier this year. This is already far more than the total US aid given out under the postwar Marshall Plan, which would be worth around $135 billion today. Around $900 billion of projects are planned or underway in total, according to credit rating agency Fitch.

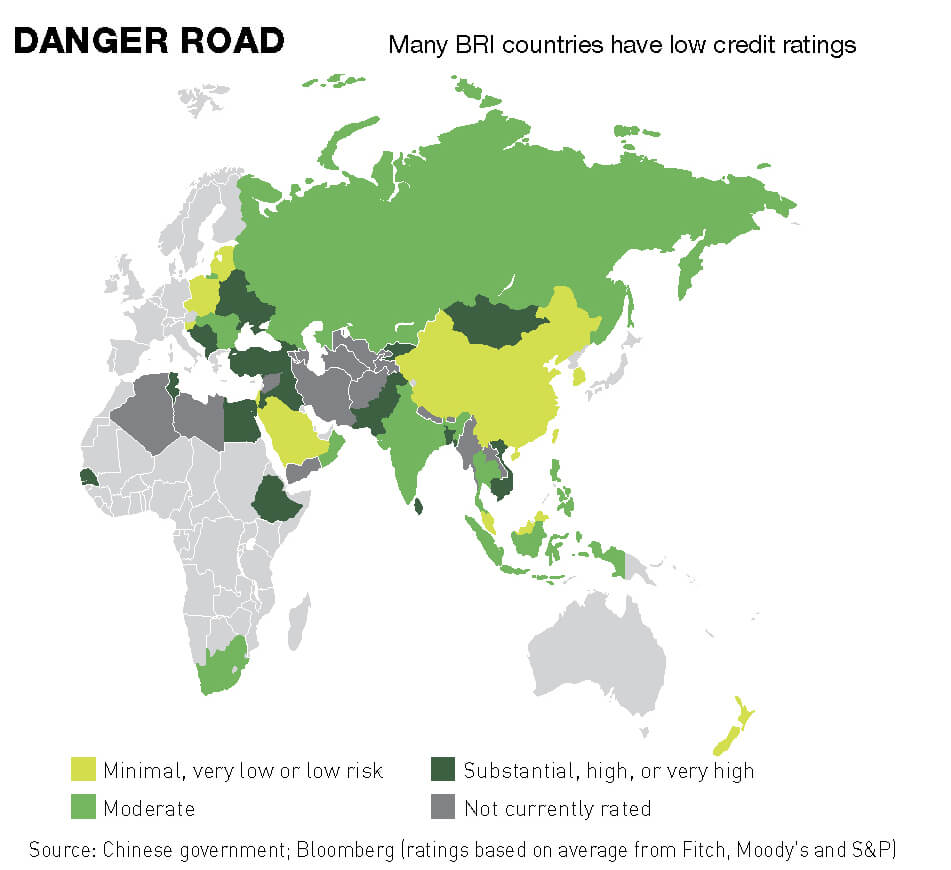

Whereas the Marshall Plan was for US allies in Western Europe, the BRI targets developing countries, including many in the highest-risk areas in the world. Of the 70 countries that had joined the initiative as of August, 27 had sovereign credit ratings of “junk” from the three main global ratings agencies, while another 14 had no rating at all.

The largest basket of projects, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, comprising $62 billion of industrial, power and transport infrastructure, runs through the troubled Pakistani province of Balochistan, where a guerrilla war between local insurgents and the government is ongoing.

Building infrastructure can provide an effective platform for growth for developing countries. Ethiopia, for example, has grown at an average of 10% per year since 2008 thanks largely to infrastructure investment backed by China. But the sheer amount of funding on offer from China has led some countries to run up large amounts of debt, putting public finances under pressure.

In sub-Saharan Africa, average public debt levels rose from 34% of gross domestic product to 53% between 2013 and 2017. Debt service as a share of public revenues has doubled, according to Geneva-based nonprofit International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development.

Pakistan has seen its external debt skyrocket by 50% over the past three years to nearly $100 billion, around 30% of which is owed to China. The country is now facing a balance of payments crisis, with its foreign exchange reserves dropping to just $10 billion by the end of June.

The Centre for Global Development, a US think tank, has also expressed “serious concerns” about the sustainability of sovereign debts of seven further BRI countries: Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro and Tajikistan.

The chance of default is high because China tends to offer financing with commercial interest rates to offset the risks involved in the projects. “Lending to BRI countries comes in a combination of aid and commercial loans,” says Su Yue, an analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in Beijing. “China’s lending has more flexibility for commercial purposes, and interest rates reflect the risk of operating in unstable countries.”

Even before the BRI kicked off, China was making loans to developing countries. Between 2000 and 2014, China lent $354 billion and 75% of these loans had commercial terms, according to researchers at William and Mary University in the United States. BRI countries take these deals because other countries are not willing to lend to them, while multilateral lenders like the IMF and World Bank often demand governance reforms and take much longer to dispense funds.

China is also willing to hand over more capital at a lower rate than commercial banks. When Djibouti was building its Doral Container Terminal, it started by borrowing $268 million from seven banks at a 9% interest rate payable over nine years. Then China offered an additional $620 billion at 2.85% over 20 years, according to Aboubakar Omar Hadi, chairman of the Djibouti Ports and Free Zones Authority.

But even at a lower interest rate, borrowing at this scale can easily tip countries into financial trouble. First, returns on infrastructure investments tend to come over a long timescale, while the loans are sometimes payable within a few years. Second, if the projects turn out to be a commercial failure, the situation can quickly become severe.

This was the case in late 2017, when Sri Lanka defaulted on repayments for loans used to finance projects including a port in Hambantota. The port cost over $1 billion, but was incurring significant operating losses.

In return for debt relief, Sri Lanka agreed to hand over the port to Beijing on a 99-year lease. This was controversial, with many accusing China of intentionally miring Sri Lanka in debt in order to gain a strategic foothold in the Indian Ocean.

The Indian scholar Brahma Chellaney coined the phrase “debt-trap diplomacy” to describe Beijing’s alleged technique. Fears spread that other countries owing China significant sums might be forced into similar surrenders of sovereignty.

Road Maintenance

But there is little evidence at this point to suggest that the Hambantota deal will be the rule, rather than an exception. As W. Gyude Moore, a former Liberian minister, pointed out in Quartz in September, China has restructured or waived loans without taking control of assets 84 times in the last 15 years.

There has also been a noticeable change in mindset from China, with the focus shifting from lending as much as possible to ensuring that projects are workable.

“In the first two years of BRI, we saw lots of activity often resulting in projects that were not very sustainable,” says Nick Marro, a China analyst at the EIU. “In 2017, we saw efforts by the Chinese government to better control overseas investment and that helps make BRI more mature.”

Many assume that BRI is a grand plan masterminded from Beijing, but the reality is that the initiative was almost a free-for-all during its early stages. Yuen Yuen Ang, a professor of political science at the University of Michigan, describes BRI as a typical example of a Chinese-style “mass campaign,” where “everyone pitches in with frenzied enthusiasm and little coordination.”

As Ang notes, there is still no government department devoted to directing BRI, only a small “leading group” made up of ministers from various offices. The group’s action plan is just seven pages long.

The dynamics of a mass campaign often leads to officials signing as many deals as possible in order to impress superiors, with little concern for whether the deals are likely to be successful long term. Beijing now appears to be attempting to counter this tendency.

In 2016, the State Council toughened up standards for state-owned enterprise (SOE) managers: should they make investments that go bad, they could face disciplinary action or criminal charges—even after they have retired. According to Deloitte, the government has also tightened scrutiny of prospective deals and introduced restrictions on the areas in which Chinese companies can invest.

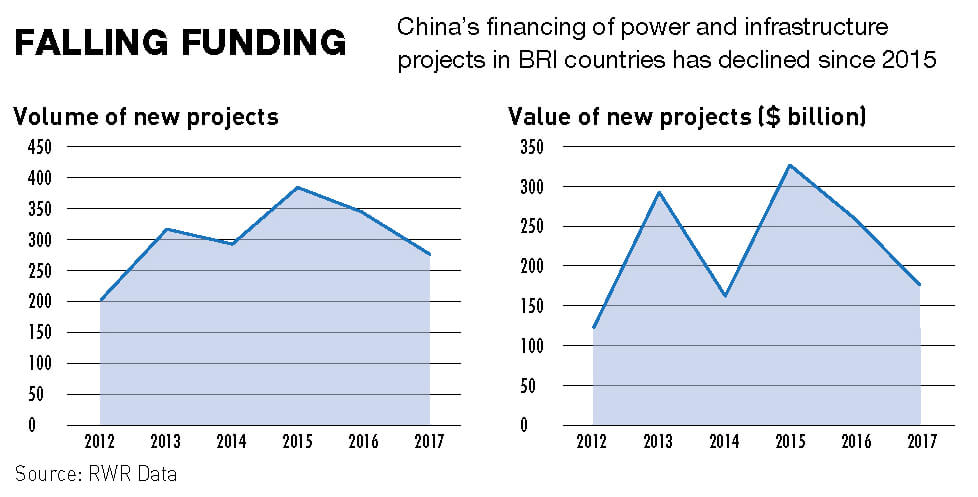

These changes seem to have an impact. In the first five months of 2018, Chinese companies signed $36.2 billion worth of BRI contracts, down 6% year-on-year, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

The rhetoric coming from China’s leaders reflects this more cautious attitude. “Ensuring debt sustainability—that is very important,” said Yi Gang, the new governor of China’s central bank, at a conference in April.

“Resources for our cooperation are not to be spent on vanity projects but in places where they count the most,” Xi Jinping told African leaders at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September.

This year’s FOCAC also highlighted how Chinese funding is skewing toward aid rather than commercial-style loans. In its latest $60 billion package of financing for Africa, China offered $15 billion of grants and interest-free or concessional loans, up from $5 billion in 2015.

Reform and Opening

The next phase looks set to bring BRI further in line with international standards. This could lead to fundamental changes in the way the initiative operates. Beijing appears to understand that the darkening outlook for emerging markets means that reforms are urgently needed.

“Current international conditions are very uncertain, with lots of economic risks and large fluctuations in interest rates in newly emerged markets,” said Hu Xiaolian, head of the Export-Import Bank of China, one of China’s two state policy banks, in July. “Our enterprises and Belt and Road Initiative countries will face financing difficulties.”

In August, Beijing issued policy papers to SOEs involved in BRI projects covering best practices in due diligence, project feasibility and ongoing operations.

According to Deloitte, Chinese firms involved in BRI are looking to reduce their interest and exchange risks and financing interest associated with long-term loans. This is leading to greater involvement for Western banks and financing companies and a more balanced portfolio of funding.

Most tellingly, several major Chinese institutions are stepping up cooperation with multilateral lenders. In April, Beijing set up the new China-IMF Capacity Development Centre (CICDC), which has the aim of developing the capacity to address implementation challenges on issues arising from BRI.

“IMF is the acknowledged leader on dealing with balance of payment crises,” said Henry Chan, an adjunct research fellow at the East Asia Institute in Singapore, in August. “The new economic realities mean that China must accelerate the learning process.”

The two Chinese policy banks, Ex-Im Bank and the China Development Bank, are also discussing cooperation with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) with a view to co-lending with it. If the two sides agree a deal, it would be a watershed moment, as the EBRD would likely insist that co-funded BRI projects adhere to international standards, including the opening of bidding processes to non-Chinese contractors.

Using a Chinese company to carry out projects has usually been a precondition for Chinese loans. Research by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) found that 89% of BRI projects used a Chinese contractor.

“EBRD has a long experience of financing projects, and a strong geographical knowledge of the market it covers, and both of these are clearly desirable for Ex-Im and CDB, who wish to learn about them,” says Agatha Kratz, Associate Director at the Rhodium Group, whose research focuses on Chinese outward investment and infrastructure diplomacy.

As China focuses more on sustainability and implementation, this opens up more opportunities for global companies to get involved by using their expertise to help Chinese contractors navigate headwinds. ABB, a Switzerland-based conglomerate, helped 400 Chinese firms resolve inter-country differences in design and industrial standards in 2016 alone.

Gauff, a German engineering firm, is working closely with Chinese SOEs on several major African projects, including the Maputo-Katembe Bridge in Mozambique, which will be the longest suspension bridge in Africa when completed. General Electric has also received orders worth billions of dollars through BRI projects and is bidding for $7 billion worth of new business over the next year or so, according to Deloitte.

The key question, according to Kratz of the Rhodium Group, is whether China will be willing to finance major infrastructure projects without insisting that Chinese companies deliver at least part of them.

“That means making sure Chinese banks’ participation really comes with no strings attached,” says Kratz.