China’s growing ties with Central and Eastern Europe have raised concerns among some in the West. But the forces pushing the two sides together are much deeper and more complex than many realize

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban shocked officials across the European Union in late January when he told a business forum in Germany that the key to his country’s future may be in Beijing, not Brussels.

“Central Europe has serious handicaps to overcome in terms of infrastructure; there is still a lot to be done in this area,” Orban said. “If the European Union cannot provide financial support, we will turn to China.”

For many, the Hungarian leader’s ultimatum confirmed a fear that has been growing inside the European establishment over the last few years: that China is becoming an increasingly attractive alternative to the EU for the investment-hungry countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Since 2012, discussion of CEE’s “turn to China” has centered on the China-Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) Summit, an annual meeting of officials and businesses from the Middle Kingdom and 16 CEE nations that is often called 16+1.

The stated mission of 16+1 is to make CEE a crucial component in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s ambitious vision for driving $1 trillion of infrastructure investment to better connect countries across Asia, Africa and Europe.

“16+1 came earlier than BRI, but it has already become supplementary to BRI, and both of them are strictly combined,” Bogdan Goralczyk, the Polish representative of the newly-founded China-CEE Institute, tells CKGSB Knowledge.

The CEE bloc is integral to China’s BRI plan: its members not only make up one-quarter of the countries along the Silk Road Economic Belt linking China and Europe, it also offers a useful route into the European Union.

“It has been obvious from the beginning that Chinese policy regarding CEE is of a strategic and long-term nature,” observes Goralczyk.

This is why 16+1 provoked unease in Europe’s traditional power centers, which see it as a strategic competitor to EU funding—and even a potential threat to European unity. “This sub-regional [16+1] approach is meeting a great deal of suspicion not only in Brussels but also in the capitals of many member states,” a senior diplomat told the Financial Times in November.

In February, German Chancellor Angela Merkel confessed similar concerns when she told a news conference: “I see great value in EU members who participate in this initiative [16+1] also representing our common foreign policy toward China, because otherwise the EU would be allowing itself to be divided against itself.”

The backlash appears to have been effective. In March, Reuters reported that Beijing is considering “paring back” 16+1 by making events more low-key, delaying this year’s summit and perhaps even moving to a biennial format.

The news may be greeted as a victory by some in the West. But the demise of 16+1 will not end Chinese involvement in CEE. The forces pushing the two regions toward engagement are, and always have been, much deeper and more complex than many realize. And these forces are likely to become stronger.

A New Player in Europe

China’s arrival as a major investor in CEE marked a historic shift for the region, which was traditionally dominated by its Western European neighbors and Russia. Before the turn of the century, the only time China had played a visible role in Eastern European affairs was during the 1950s, when the People’s Republic helped prevent a possible Soviet invasion of Poland, according to the China-CEE Institute’s Goralczyk.

However, Chinese involvement in CEE soon waned as Sino-Soviet relations became increasingly hostile during the 1960s. It was not until the early years of this century that the Chinese reappeared in the CEE, this time as an emerging global power and the world’s fastest-growing market economy.

This return was driven more by hard-headed business interests of Chinese companies than any geopolitical interests of the Chinese government, says Agnes Szunomar, a senior economist at the Centre for Economic and Regional Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

“Chinese companies like Hisense, Huawei and ZTE entered for the same reasons Korean and Japanese companies entered a decade before them: it was market-, efficiency- and strategic asset-seeking, where the main point is access to the EU market,” says Szunomar.

China’s “go global” policy, launched in the run-up to its World Trade Organization accession in 2001, encouraged its businesses to become internationally competitive. Meanwhile, the accession of 10 CEE countries to the EU in 2004 made the region an attractive investment destination. Not only was it a market of 100 million consumers with excellent growth prospects; it also offered a combination of low-cost labor and frictionless trade with Western Europe.

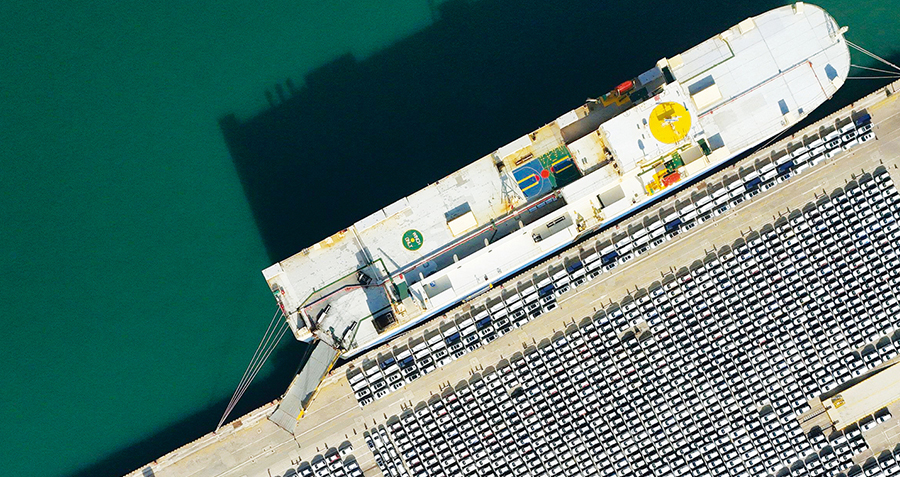

Between 2009 and 2012, China-CEE trade jumped from $32 billion to $52 billion, according to data from the China-CEEC Institute. Chinese investment also grew quickly, particularly in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis when Chinese companies bought up large numbers of ailing European firms.

It was not until the second decade of the century that China’s interest in CEE became more strategic, with then-Premier Wen Jiabao putting forward a 12-point plan for deepening China-CEE relations at the second China-CEE Business Forum in Warsaw, Poland, in 2012. Wen found a receptive audience, according to Szunomar, because many CEE countries had become disillusioned by the realities of EU membership.

“The new EU member states became disappointed with the EU… because they thought they could catch up to Western Europe faster,” explains Szunomar. “So, now some CEE countries see China as a new potential ally.”

Wen’s speech led to the setting up of the annual 16+1 summit. It also inspired the creation of a special China-CEE secretariat in Beijing that coordinates a mixed architecture of financial cooperation, infrastructure projects, cultural and educational exchanges, and other economic and investment measures.

During the 2017 summit, Premier Li Keqiang, Wen’s successor, announced the establishment of a China-CEEC Inter-Bank Association and a second phase of the China-CEEC Investment Cooperation Fund, which will provide the new Inter-Bank Association with $2.4 billion of funding via the China Development Bank.

The 16+1 project is an unambiguously Chinese-run affair: the secretariat answers directly to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing and all ranking officials are Chinese. European participation is limited to the “national coordinators” from each member country.

Phantom Menace

That 11 EU member states are also part of such a Chinese-led club has caused unease in Brussels, with many voicing concerns that Chinese influence in CEE could undermine any common European China policy. According to Lucrezia Poggetti, a research associate at the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), this concern has been increasing since mid-2016, when reports emerged that Hungary and Greece—both recipients of Chinese infrastructure investment, though the latter currently only has observer status at 16+1 summits—had watered down a joint EU statement criticizing China.

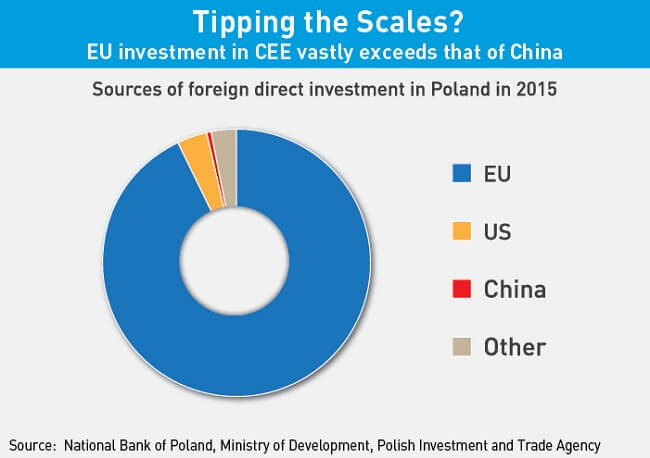

“It is difficult to say whether these countries changed their rhetoric to gain leverage in their negotiations with Brussels or to curry favor with Beijing in the hope to obtain investment,” comments Poggetti. “Nonetheless, it raises concerns at the EU level and in Germany.” Poggetti points out that there is little evidence to suggest that 16+1 is a realistic threat to Brussels’ dominance in CEE, since China’s financial leverage over the CEE countries is minimal. “This threat is mainly still a matter of perception,” she says.

“The European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund poured into CEE far outweigh what China does in CEE,” Poggetti continues. “And for all 16 CEE countries, access to the EU market and Germany in particular is economically vital, so Germany has substantially more leverage than China over them.”

According to Szunomar, even in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia—the four CEE countries that have historically received most investment from East Asia—Europe accounts for 90% of foreign direct investment. The rest comes mainly from the US, South Korea and Japan, with China in fifth place.

“These statistics don’t track back to the ultimate owner, so in reality Chinese investments are more significant,” notes Szunomar. “Nevertheless, Japanese and Korean companies still have more investments in the [CEE] region as they arrived almost one and a half decades earlier.”

A Shaky Platform

While Western Europeans worry about China’s increasing influence in CEE, many in Eastern Europe have the opposite concern: 16+1 has so far failed to provide the surge in Chinese investment and trade that they had hoped for. To date, China’s state-run banks have only signed off on $15 billion worth of deals for infrastructure-related projects in CEE, according to data collected by the Financial Times in cooperation with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington-based think tank.

What’s more, Szunomar points out that, “a lot of the [Chinese] investments were actually made before the establishment of the 16+1 cooperation.”

Major projects undertaken include a bridge in Serbia, two roads in Macedonia and little else. There have been high-profile setbacks, such as the Macedonian Ministry of Transport and Communication’s decision last year to block the completion of a Chinese-financed 57-kilometer, $460-million highway amid allegations of corruption and losses to the state budget of over $190 million.

According to Richard Turcsanyi, Director of the Strategic Policy Institute in Slovakia’s Bratislava, many potential deals have fallen through because Chinese investors have been reluctant to offer good terms or comply with European procedures. “Many projects are based on unrealistic plans because China doesn’t want to accept public tenders and comes up with loans that are more expensive than on the financial market,” he says.

Growth in trade between China and CEE has slowed significantly since the founding of 16+1. After nearly doubling between 2008 and 2012, total trade grew by less than $7 billion over the next four years, reaching $58.7 billion in 2016.

Frustratingly for CEE countries, most of this extra trade is fueled by increasing Chinese imports, not exports to the Middle Kingdom. The 16 countries’ trade deficit with China has continued to increase since 2012, with imports from China outnumbering exports twelvefold in 2016.

“The much hoped-for boost of exports to China has not materialized,” says Turcsanyi. “CEE countries typically manufacture intermediate products for Germany, from where the final products are then shipped to China.”

According to Szunomar, the underwhelming results are due to “insufficient knowledge of regulatory and business practice among Chinese companies,” as well as “the small number of investment opportunities presented by CEE companies to Chinese investors.”

Western Retreat

Given the low levels of Chinese investment in CEE up to this point, the importance attached to 16+1 from both sides of Europe—the Eastern Europeans hoping that China is the answer to their development needs, and the Western Europeans fearing the same—appears out of proportion.

According to Wang Yiwei, Director of the Center for EU Studies at Renmin University of China, the reason for this perhaps lies not so much in China’s growing ambitions in Eastern Europe, but rather in the West’s retreat from it.

“The US is becoming less interested in participating in European issues, and those leading countries in the EU, in many cases, can’t even solve their own problems,” says Wang. “This is why the CEEC is seeking opportunities from China.”

Poland, for example, could lose its EU development funding—currently set at €80 billion ($98 billion)—once the next seven-year budget round begins in 2021 due to Brussels’ plans to link access to the funds to countries’ “judicial independence” and “solidarity.” If Poland were to lose this EU support, it would be forced to look elsewhere for funding, according to Mercy A. Kuo, President of the Washington State China Relations Council, a US-based non-government agency.

“The EU structural funds for development will stop in 2020, and Poland needs to seek alternative investment vehicles to prolong its GDP growth,” Kuo wrote in a recent article for The Diplomat. “Huge investments are still needed in infrastructure, especially train lines and the energy sector.”

The Balkan nations’ hopes of joining the EU, meanwhile, have receded, so they are searching for a new way forward. Gjorge Ivanov, the president of Macedonia, which has been a candidate for EU membership since 2005, has been frank about why his country needs to develop closer ties with China.

“As Europe is withdrawing—or rather not keeping its promises about making the Balkans part of the European Union—it’s like a call from the EU to come and fill in that space,” he told The Telegraph in November.

As Kuo points out, with the EU’s budget set to shrink after Brexit, Europe will be in an even worse position to help CEE nations develop. For these countries, it will become even more necessary to attract increased investment from China.

Green Shoots

Fortunately for CEE, there are signs that this is finally happening with direct investment from Chinese companies appearing to be picking up. Poland saw a flurry of big deals in 2016, including the China Three Gorges Corporation’s €289 million ($350 million) deal to take over Portuguese EDP Renovaveis’ wind farms; China Everbright’s acquisition of Polish waste and alternative fuel company Novago for $117 million; and NovoTek Pharmaceuticals’ investment in insulin producer Bioton.

There were also greenfield investments by Suzhou Chunxing Precision Mechanical and Hongbo Opto-Electronics in plants to produce precision mechanics and street lights, respectively. According to Agnieszka McCaleb, a researcher at the Warsaw School of Economics’ East Asian Research Unit, the turnaround has come from Chinese investors learning from past mistakes, such as COVEC’s abortive project to build a highway connecting Warsaw with Germany before the Euro 2012 soccer championships.

“COVEC’s failure delivered a significant blow to the reputation of the Chinese in Poland,” says McCaleb. “But this has recovered as Chinese companies won bids and learned to work more closely with local subcontractors. Chinese direct investors also look for assets strategic for them in terms of technology, such as those related to waste management, renewable energy and the prevention of pollution.”

Eastern European companies are also learning to use 16+1 as a matchmaking platform to secure deals with Chinese buyers, according to Gabor Holch, a Hungarian consultant who advises EU companies operating in Asia. Holch notes that 16+1 is vital for helping connect small European and Chinese businesses that otherwise would never meet.

“One option for these two to come together is a government-funded delegation,” he says. “The other option is Hungarian-Chinese trade fairs organized by a business chamber. And that is precisely where 16+1 comes in, as there are countless such activities organized under its umbrella.”

Winners and Losers

For Eastern European business people like Holch, there is no reason that CEE economies should choose between the EU and China. “They need both markets and that need would also be applicable to the political realm,” he says.

From Holch’s perspective, 16+1 is helping companies from CEE do what their Western European neighbors have done before them: take full advantage of the Chinese market. According to the Hungarian, CEE companies are increasingly looking to team up to realize “production in China, such as the French do with their wine, but that can only be achieved with overarching government support through 16+1.”

However, the question is whether those in Western Europe can be persuaded to see it that way. There are also signs that Western complaints about European unity mask more self-interested concerns. According to Michael Christides, Secretary General of the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, this is visible in the attitudes of some in Brussels toward China’s investments in ports in the western Balkans.

“[There are] fears the big ports of the north, like Rotterdam and Hamburg, could lose a lot of trade volume” because of competition from new southeastern facilities, Christides told a forum in Greece last year. “This is widely discussed in Brussels.”

Though it will be painful for many in Europe to hear, Hungarian leader Orban is perhaps right to remind them that “it is now obvious that the world economy’s center of gravity is shifting from West to East.” Brussels can choose to embrace Beijing’s presence in Eastern Europe, or resent it. But it cannot stop it.