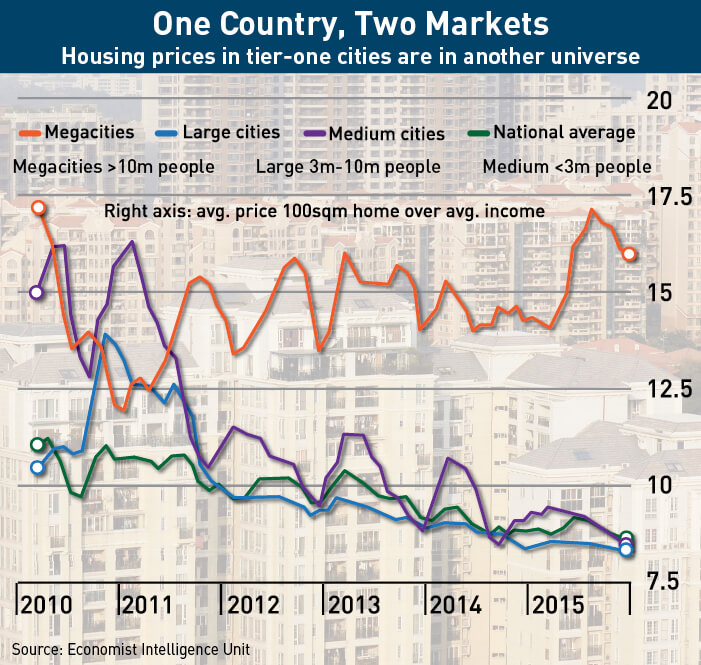

China’s housing market in top-tier cities has been on fire for years, while in lower-tier cities it may be straining under the weight of oversupply. But is there a looming crisis? In the near term, the answer seems to be no

Just when it seemed they could not go much higher, property prices in China’s tier one cities made another gravity-defying leap last year. By September, new home prices had jumped 27.8% in Beijing, 32.7% in Shanghai and a meteoric 34.1% in Shenzhen year-on-year. Reacting to the news, China’s richest man, property mogul Wang Jianlin, declared the country’s real estate market the “biggest bubble in history.”

By December, price growth had slowed a bit, but this has done little to calm the tone of many commentators who see disaster looming. China’s property market was virtually non-existent 25 years ago, but it is now one of the most critical pillars in the world’s second-largest economy and the source of incredible wealth for many of China’s citizens. The health of this pillar remains a top concern of the government and citizens alike.

The price increases in recent years have been dizzying. Valuations in many Beijing and Shanghai districts are now comparable to those in other major international cities, even though average salaries are well below those of the West. According to Numbeo, a consumer price tracking website, in May this year the average price per square meter for a flat in central Beijing or Shanghai was approximately $13,000. In New York it was $11,800 and central London $18,000.

People who bought early have done well. Lynn Huang, a 34-year-old co-founder of a private English academy in Shanghai, bought an apartment in the Pudong district of the city seven years ago for RMB 13,000 ($1,900) per square meter. Its value has risen to RMB 50,000 ($7,300) per square meter, but she cautions this is to some extent theoretical. Government restrictions introduced late last year to take the heat out of the market mean she cannot easily sell the unit.

“The price is rising, but as long as I cannot sell it, it is just paper value,” she says. “It doesn’t mean anything to me… I still have to work.”

Growth of a Nation

After the communist victory in 1949 and until the early 1990s, there was no Chinese housing market. People lived in communes in the countryside, or in work-unit housing in urban areas. In neither case did they own the accommodation.

China began opening up to the world after 1978. Reforms then, and again after 1989, resulted in a sell-off of urban state-controlled housing to residents and the beginnings of a property market. Initially people were unhappy with the change, as it meant paying for an item once provided free of charge, but it was an asset sale at bargain basement prices, and as the economy picked up, so did property values. In 1995, a small, 60-square-meter apartment in Beijing cost about RMB 200,000 ($30,000). That same apartment could now sell for RMB 5.5 million ($810,000).

Today, housing is a major store of value for Chinese people. According to a survey by the state-run Economic Daily of 25,000 families across 25 provinces, real estate accounted for 65.61% of per capita household wealth in 2015. “For most individuals the single biggest investment in mainland China is a house,” says David Hong, Head of Research at E-house (China) Enterprise Group in Hong Kong.

Driving the rapid price increase are investors piling into the market. A dramatic stock market rout in 2015 in particular left many seeing property as one of the few secure investment options available on the Chinese mainland. “There are few investments products that offer the same degree of security as real estate,” says Sam Crispin, CEO of ABP Investment Management in Hong Kong.

China’s banks also see property as a secure bet. About half of all new lending in 2016 went into real estate, largely through mortgages with bank loans to developers and homebuyers totaling RMB 26.68 trillion ($3.87 trillion). This was up 27% from 2015, according to data from China’s central bank. Agricultural Bank of China, the country’s third-largest lender by assets, had 82% of its new loans go to housing.

Wealth Lockout

The creation of the housing market led to the emergence of China’s middle class. It has helped create vast wealth in many parts of society and has had a huge positive impact on the economy, the growth of which for 30 years now has exceeded more than 6% annually—the fastest sustained economic growth in history.

About 70% of middle class wealth in China is tied-up in property and this group is carrying China’s consumer economy forward. “The explosive growth of China’s emerging middle class has brought sweeping economic change,” wrote McKinsey in a 2013 report, Mapping China’s Middle Class.

Unfortunately, not everyone caught that first property wave in the 1990s, and with the sharp and continued rise in prices, many people now seem permanently locked out of the market. Those migrating from the countryside to the big cities have even less chance of buying a home. With urbanization proceeding rapidly in the world’s most populous country, this is creating serious social pressures.

“A property-owning class is emerging that is quite distinct from the non-property-owning class,” says Michael Cole, founder of China real estate analysis website Mingtiandi. “The only way for young people to afford a house, for example, is with assistance from their parents. The only way their parents have that kind of money is because they themselves have bought property.”

Alan Li, a 28-year-old consultant at an education company in Beijing, believes his chance of owning a home is distant at best. “Property in Beijing is way overpriced and it puts a heavy burden on the people of this city,” says Li.

The sky-high prices in China’s top-tier cities have not only seen the emergence of a divide between haves and have-nots, but the overall situation of unaffordability has also raised the specter of social instability. According to Numbeo, the price-to-income ratio for New York City housing is 13. Beijing’s ratio is more than 33 and Shenzhen’s more than 44. In other words, for the average person, it can now takes more than 30 years’ salary to be able to afford a 90-square-meter flat in the central areas of China’s main cities.

With the cost of buying an apartment so high, the lifetime fortunes of homeowners and their families ride on the property market remaining solid. The government is aware of this, but also of the mounting discontent at the rising prices and is attempting to “contain excessive home price rises,” according to a recent statement. Authorities, however, cannot afford to clamp down too hard because the economy also depends on a buoyant property sector.

According to Moody’s Investors Service, about 25% to 30% of China’s GDP is linked to the property and construction sectors. “This means developments in the property market can have large macroeconomic effects,” said Michael Taylor, a Chief Credit Officer for Asia-Pacific at Moody’s, in a report in March.

Property development and apartment sales are also key sources of revenue for local governments, so they have an incentive to keep land sales going. According to the Chinese business magazine Caixin, income from the sale of land-use rights totaled RMB 3.75 trillion ($551 billion) in 2016, nearly 30% of the combined annual income of local governments, with some areas depending on sales for as much as 50% of their revenue.

“Property is the goose that lays the golden egg,” says Crispin. “They (governments) are dependent on that revenue stream—if they lose it what will take its place?”

Decompression

The Chinese government has a greater responsibility for the stability of the national housing market than governments in other countries because in China there is no freehold ownership. All property, including apartments, villas and factories, have only usage-rights leases with a maximum duration of 70 years. The state remains the ultimate owner.

Nobody, the government included, understands the full implications of this because the market is still so young. But a small window on matter opened up last year. In April 2016 in the eastern city of Wenzhou, some residents were dumbfounded when the local government informed them that the 20-year usage period on their homes had expired and a payment of up to one-third of current market value was required to roll over the leases. Homeowners were irate and quickly took to social media to protest.

A tense standoff lasted for months as the government grappled with a precedent that had national implications. In late December, it was announced that the Wenzhou leases would be rolled over free of charge, which kicked the issue down the road but left the core issue of ownership rights unclear. Such uncertainty, long-term, is a destabilizing factor.

“[A bursting bubble] would be catastrophic for the Chinese state,” says Crispin. “The government is in control of land sales, the government is in control of construction, the government basically sets prices by approving the pricing of sales… so it’s the government’s fault if it goes wrong. They have no mechanism to cope with [a crisis].”

Measures implemented in recent years have tried to cool down the market. These include raising minimum downpayments, which can be up to 80% in major cities, and outright restrictions on home purchasing, for example by making it illegal in some places to buy a second apartment.

Such restrictions can, however, have the opposite of the intended effect. “Qualified buyers will treat policy tightening as a signal of ‘buy!’,” says Hong of E-house. “If there is a policy tightening, that means demand is far higher than supply, so I must buy if I am qualified. People will then try every way possible to make themselves qualify.”

Results have ranged from the predictable, like using a relative’s name to buy a second apartment, to the creative. Late last year there was a spike in divorces in Beijing and Shanghai as married couples discovered a legal loophole. More rules followed concerning how long you had to be divorced before you could buy a “place of your own.”

For people like Lynn Huang, the whole thing is a headache. Her job is about a one-hour commute from the apartment she bought years ago and she would like to sell it and purchase a new one. However, the new rules mean she has to wait six months after the sale to buy a new apartment. Not wanting to run the risk of ending up “homeless,” Lynn now has an empty apartment on one side of the city and a rented unit on the other.

For others, control policies cause real grief. Some developers have marketed commercially-zoned real estate as residential—this offered cheaper prices for those aching for first homes, even though it was illegal. When Shanghai decided to enforce the law and void those sales this June, about 100 people came out to publicly protest—days later the government relented.

Bubble, or Not?

Whether or not these problems amount to a “bubble” is highly debatable, especially as demand shows no signs of abating.

One of the factors that will continue to support prices is an intense cultural desire to own a home. Having an apartment is usually a prerequisite for marriage in China, which means people buy early. According to a survey by HSBC earlier this year, 70% of Chinese born 1981-1998 already own property. The equivalent number is only 35% in the United States.

At a glance, this seems strange given the enormous gap between incomes and home prices. Close relatives, however, usually help foot the bill. “Lots of people argue that as housing prices get higher and higher, that you may need 20 years without food in order to buy a house in Beijing for a normal household,” says Hong. “[But] most people buy a house with the sponsorship of their parents.”

Hong describes how decades of the one-child policy (scrapped only last year) have created an inverted pyramid family structure. This means the financial resources of two parents, and even up to four grandparents, can be marshaled to buy a house for a single offspring on a meager salary.

Surprisingly, not all Chinese property buyers are inclined to believe that property prices are too expensive. “I think prices are reasonable,” says Lynn Huang.

David Hong agrees. “Although the property prices sound high… [they are] still in a reasonable range,” he says. Even if China real estate is, as some believe, a bubble, it would appear for the near future to be an iron one and not in danger of bursting.

“I never use the term bubble because it gives people the sense that this is a US-type of situation,” says Cole from Mingtiandi. He expresses exasperation with foreign-based analysts who predict imminent collapse based on loose parallels to Western markets.

China’s property market is clearly different from that of the United States, the epicenter of a housing crisis that in 2008 resulted in the largest global financial crisis since the Great Depression. Using the US subprime crisis as a measuring stick of bubbles reveals the differences. China’s lending rules are far stricter, they demand far larger down payments and all mortgages are held to maturity by the issuing banks.

Still, there are grounds for disquiet. Some Chinese financial institutions have circumvented restrictions through “shadow” lending, most prominently via wealth management products (WMPs). These off-the-books instruments are poorly regulated and non-transparent. The International Monetary Fund has flagged WMPs as presenting a systemic risk to China’s financial sector. According to the China Banking Wealth Management Registration & Depository Center, which tracks WMPs, about RMB 2.5 trillion ($368 billion) derived from these funds was invested in property in the first half of 2016, or 13% of total WMP funds.

The fact that modern China has never experienced a significant real estate correction also has some people worried. Given the importance of the property market to China’s financial wellbeing, any trouble arising in housing prices would affect the wider economy, which would then feed back into the property market.

For the past few years, the Chinese government has been spending furiously to keep GDP from dropping too fast—China’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 279% in 2016 (the US is currently about 104%). One of the primary destinations for stimulus is China’s “old-economy industries,” such as steel and concrete. These are, of course, building materials and while some of it goes into infrastructure projects or are exported, much goes into housing development.

Tiered Cities, Tiered Housing

China’s biggest property problem may be that the market is immature and people have known only good times since it opened up less than three decades ago. The market is psychologically poorly prepared for a downturn. Hong tempers his long-term outlook for just that reason.

“It is not a mature market like the US,” he says. “You’ve never seen a real bubble burst in mainland China, so no one can tell you what the [consequences will be if it happens].”

The sharp rise in prices in China’s top-tier cities in recent years has not only seen the emergence between haves and have-nots, there is also a widening gap between the first-tier cities and other parts of China. While the property market in Beijing and Shanghai remains tight, cities elsewhere face the opposite problem of empty apartments.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China had more than 450-million-square-meters of unsold residential housing space at the end of 2015, an area twice the size of Boston. A 60-square-meter apartment in the center of Xi’an, a city of almost nine million people in northwest China, would cost about RMB 650,000 ($96,000), an eighth of the price in Beijing.

David Hong from E-house speaks plainly. “[Some central cities] need to figure out a way to digest that supply,” he says. “Or eventually [prices] will collapse.”

The scale of this potential problem is so large as to sometimes appear almost comical. An analysis by Chinese state-run Xinhua News Agency in July 2016, for example, said new projects planned by China’s small cities could accommodate 3.4 billion people by 2030, or two-and-a-half times larger than China’s current population.

Building the Future

The Chinese government is invested heavily in keeping the property market strong, but not too strong: it is a balance that is difficult to maintain. “I think [the market] should be open,” says Lynn. “But the government should provide… cheap apartments for the people that can’t afford it, like Singapore.” Singapore provides housing for about 80% of its population. While China has subsidized housing, few people have been able to benefit, according to a Caixin report in April.

An answer to the government need for buoyant revenue would be a property tax. The authorities in Shanghai and Chongqing have tried to implement such a tax on a test basis, but have abandoned efforts due to virulent opposition from property owners. A more practical solution for big cities would be to release more land for residential development, which is something that Beijing is doing. In April, the government in the capital announced it would make land available for up to 1.5 million new homes between 2017 and 2021, in the hope that that will cool the market.

“Part of the government’s focus this year is trying to find an alternative to one-size-fits-all solutions to housing issues,” Michael Cole says.

Sam Crispin, on the other hand, still sees government policy as confused—boosting big cities where the economy is booming, at the expense of smaller cities that have been left out. “It is the most successful cities that get more government support, like free trade zones,” he says. “Why not make the whole of China a free trade zone? Or put them in the less developed parts of the country?”

Many ordinary people are just plain worried, especially in light of historical precedent. “Japan’s housing market crashed in the 1990s and [it] is still struggling to pull itself out,” says Alan Li, the consultant in Beijing. “The government is doing everything possible to prevent that.”