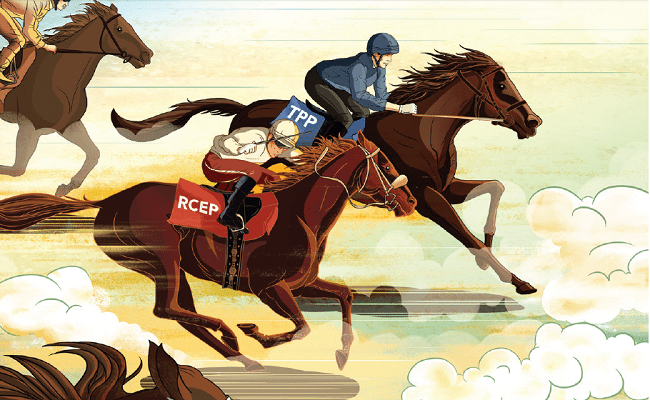

Setting new standards in Asia following the demise of TPP

As members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) met in Manila in November 2015 for the group’s Leaders’ Meeting, a subsection of attendees gathered on the sidelines to celebrate the completed negotiations of a new landmark trade deal—the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). At that stage, TPP member countries were keen to acknowledge the hurdles involved in ratifying the deal, but even then-US President Barack Obama could not have envisaged what was to come when he said at the meeting, “[Execution] is not easy to do. The politics of any trade agreement are difficult.”

Following an election marked by concerns of trade and economic disparities, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order on 23 January taking the US out of the TPP, fulfilling a significant campaign promise in the process. With involvement by the US and Japan necessary for the implementation of the TPP in its agreed form, the newly installed president brought the curtain down on an agreement that took five years of negotiations with a pen stroke.

With that failure, the spotlight has now fallen on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a proposed trade deal between the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand—countries that ASEAN already has free-trade deals with. And that membership has lent the deal a certain degree of significance—the countries involved account for about 30% of world GDP and over a quarter of world exports.

But although developing out of existing trade frameworks and having its roots in previously proposed agreements, such as the Japan-led Comprehensive Economic Partnership for East Asia, the RCEP is now largely seen as a Chinese initiative and a way of pushing back against US influence in Asia.

However, progress on the RCEP has been slow, with the pact’s guiding principles, which were set out in 2012, envisaging a completion of negotiations by the end of 2015. But there is increasing optimism that will change, with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade stating in a 10 March news release on the 17th round of negotiations that, “It was clear in Kobe that participating countries recognised the need for the negotiations to intensify, particularly in light of recent global developments”.

Back to the old school

The guiding principles of the RCEP set out several areas of negotiations, and these include trade in goods; trade in services; investment; economic and technical cooperation; intellectual property; competition; dispute settlement; e-commerce; small and medium enterprises (SMEs); and other issues. Precisely what has been agreed so far remains up in the air, with much of text remaining secret, as is often the case with such trade agreements. But chapters on SMEs and technical and economic co-operation have reportedly been closed, and new offers on goods and services will be tabled at the next round of negotiations, scheduled for 2–12 May in the Philippines. Yet even at this stage limitations of the RCEP are apparent.

While in office, Obama said that “China can’t be allowed to write the rules on trade”. But it is not clear that the RCEP would allow it to do so, with the agreement having a much narrower scope than the TPP. The topics of labor, the environment, and state-owned enterprises are missing, for example. That has seen the RCEP cast as a “20th-century agreement”, with the barriers to trade in the form of regulations and standards that the TPP attempted to tackle being ignored or addressed only partially.

“As currently envisioned, the RCEP is not a significant regional economic co-operation proposal,” said Scott Kennedy, deputy director, Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Its focus is on traditional tariffs, and it would not significantly address investment, IP, competition policy, and other issues screaming for attention. I don’t expect the RCEP to be broadened because there is nothing approaching a consensus among the negotiating parties that the agreement should be more wide-ranging.”

Indeed, the limited scope of the RCEP plays well with some negotiating parties’ current interests, particularly the country seen to be driving the deal.

“The RCEP suits China well in that it focuses on reducing tariffs, while playing down labor conditions, intellectual property rights, and environmental standards,” said Leslie Young, professor of economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

And further undermining hopes for the RCEP evolving into the kind of trade deal for which the TPP set the benchmark is the way in which the participating parties were brought together.

“I always say that these countries were ‘drafted’ into the agreement”, said Deborah Elms, founder and executive director of the Asian Trade Centre, a Singapore-based research institute. “They did not volunteer to join a comprehensive, high quality deal. They are there because they had an existing agreement with ASEAN. Hence their overall enthusiasm for market liberalization with one another varies.”

Indeed, in terms of significant breakthroughs, much of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked, and this is “leaving RCEP officials grappling with how much to open or address more sensitive goods,” according to Elms. “In particular, the RCEP means opening up markets between the ‘plus-six countries’, especially including China, India, Japan and South Korea to one another. These partners do not already have existing agreements.

“This is slowing down progress considerably,” she added.

A further issue for the fledgling trade pact is the diversity of its constituent parties, with the economies varying significantly in scale and sophistication—GDP per capita, for example, ranges from $1,159 in Cambodia, the lowest figure of all the RCEP countries, to $56,311 in Australia, the highest, according to the World Bank. With that comes difficult and possibly unpalatable trade-offs.

“Indian leaders would like to broaden access for its exports of its services, but fear that their weak manufacturing base would be swamped by Chinese exports,” said Young.

Down but not out?

With the RCEP offering relatively limited benefits and the presence of several challenges confronting the deal, strong incentives for the TPP or a “TPP-lite” will remain, and Elms noted that the “RCEP will not deliver the same results [as the TPP]”.

“The RCEP will not drive the same domestic-level reforms that many TPP countries were hoping to achieve. It will not lead to new sources of competitiveness or, perhaps, economic growth,” she said.

But exactly what form a revived TPP may take remains to be seen, with various TPP members distancing themselves from such an arrangement. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, for example, has said that the TPP is “meaningless” without the US. Meanwhile, Malaysian International Trade and Industry Minister Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed has said that the country does not intend to pursue a TPP-lite agreement “as it does not meet our primary objective of gaining access to markets such as the US, Canada, Mexico, and Peru”, and that the RCEP is seen as “the second-best option”.

At the same time, others have moved to back a revised agreement. Despite being branded as “meaningless” without US involvement by Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the TPP was perhaps given a new lease of life after Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga told Kyodo News in April that “the 11-nation framework [without the US] should be given weight”. In addition, Australia and New Zealand have even gone so far as to float the inclusion of the country TPP purposefully excluded. “We are not about to walk away … certainly there is potential for China to join the TPP,” Malcolm Turnbull, the prime minister of Australia, said in January.

Indeed, Kennedy believes that an eventual agreement is likely somewhere down the road, with the remaining 11 countries sticking together, or subsets of members moving ahead together, perhaps also with countries that weren’t negotiating parties before.

“I also wouldn’t rule out the possibility that the US could eventually change its mind and decide to return if it could get improved terms on certain sectors, such as autos and agriculture,” he said.

In any case, it might well be that RCEP stands out for its geopolitical ramifications, particularly if the deal sees China trading access to its economy in exchange for a greater say in global affairs.

“Despite being an ASEAN initiative, RCEP’s main significance is as a sign of growing China’s regional influence,” said Kennedy.