Just a few years ago, China was a major obstacle to a global agreement on climate change. But the attitude of the government has changed, to the delight of all. That said, it will take more than good will to clean up

In September last year, China finally ratified ambitious targets for the reduction of CO2 levels through the lessening of carbon intensity and improvements in environmental regulation. The targets, agreed at the Paris Climate Conference in 2015, marked a surprising turnaround for China, which, at the Copenhagen Summit in 2009, determinedly blocked environmental restraints on its developmental trajectory.

Since that 2009 low point, the world has seen the emergence of the word ‘airpocalypse’ to describe the toxic miasma that now often enshrouds Chinese cities, an air pollution nightmare that has sharply pushed up mortality rates for residents.

The scale of China’s dilemma and the ambitious edicts emerging from Beijing have cultivated a sense that it could take on a global leadership role. But the reality on the ground is still so far been mixed.

The government has invested heavily in renewable energy, becoming the global leader by a wide margin, with a third of the total in 2015. But at same time, the country is still heavily reliant on coal—to say nothing of the problem of idle wind and solar capacity. Additionally, last year China massively ramped up its issuance of so-called “green bonds” to finance projects, coming out of nowhere to make up more than a third of the global market. But looser domestic standards are cause for pause.

And although the intense focus on reducing air pollution is doubtlessly good, water or soil contamination gets decidedly less attention, despite being potentially more serious. And even so, the air scarcely seems to be getting better—by official counts, in 2016 Beijing had 12 more “blue sky days” than the previous year, but still nearly half the year saw moderate to severe pollution.

The rising pressure on Beijing to act is therefore mostly domestic. The smog wave of recent years has raised “doubts about the government’s declared ‘war’ on air pollution,” according to Gavekal Dragonomics, a Beijing-based macroeconomic research firm. Indeed, last December the foul air prompted environmental protests in the southwestern city of Chengdu and the sharp response from the authorities suggests that the central government is rattled.

What this means is that despite the positive signals of Beijing’s international agreement, the moves it is making are not fundamentally internationally focused, says Damien Ma, Fellow and Associate Director of the Paulson Institute Think Tank, which focuses on US-China relations and sustainable growth.

“China was going to take a lot of these actions anyway for its own national interests,” he says.

But either way, given the size of China, what it does to address pollution domestically has international significance. In this way, the problems may be seen as an opportunity to lead—if China can get a grip on the domestic crisis.

Internalizing Externalities

The wider backdrop to the failure of Copenhagen was of a world reeling from financial crisis and of China launching an enormous stimulus program to keep growth rolling, the bulk of which constituted big capital investments. The none-too-subtle message was that the environment would have to wait, which played into the notion that economic growth and environmental protection are naturally opposed.

But grappling with the real cost of the externalities—that is, the hidden costs of pollution—have helped force a rethink. The World Bank estimates that unconstrained pollution cost upwards of 5% of GDP for China as long ago as 2003; current forecasts estimate continuing costs of approximately RMB 1 trillion ($145 billion) per year.

Putting these externalities in human terms is all the starker. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet, air pollution in China caused 1.2 million early deaths 2010 alone.

But the bigger driving factor may be the visibility, or lack thereof, that comes with the choking smog. The problem is just so extensive that the old methods of deny and condemn no longer work—it is in the face of every citizen with disturbing regularity. Damien Ma even thinks an overlooked silver lining in this cloud of acrid smog is simply that it is very intense in Beijing, which he says is a good thing “because it will continue to garner political attention.”

Supporting this view, a recently published book, The Economics of Air Pollution in China, written by Ma Jun, Chief Economist at the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), lays out “ten specific policy measures to drive structural adjustments” premised very much on the necessity of doing so rather than on ambitious estimates of the benefits. The plain fact that the Chief Economist at the PBOC has published such a book must be taken as a measure of China’s commitment, but interestingly, the book “examine[s] the likely impact of [the recommended] policy measures” calculating that they “will not lead to a substantial deceleration of economic growth from 2013 to 2030.”

There are also extensive environmental reform commitments within the latest Five-Year Plan (FYP), currently being expanded into regional and sectoral details. The significance of this cannot be underestimated.

“[In the past] officials would have mixed messages coming from the center, on the one hand to protect the environment and on the other hand to boost GDP growth, when they knew that really the only one that mattered was GDP growth,” says Sam Geall, Research Fellow on Low Carbon Innovation in China at the University of Sussex. Now, he believes the political priorities have changed. “If you have environmental violations on your record they stay on your record for the rest of your career… that helps to shift the ways in which things move at a local level.”

What all this means is that the CO2 commitments within the Paris Agreement are just the secondary co-benefits of dealing with the atmospheric particulates cloaking China’s skies.

“China has a huge pollution problem—one might even say, a pollution crisis—that has become a public concern it can no longer ignore,” says Patrick Chovanec, Managing Director of Silvercrest Asset Management. “If China’s environmental policies are changing, it has more to do with that far more immediate concern than with ‘climate leadership’.”

It should, however, be acknowledged that the Paris Agreement is an important, if insufficient, step. At least now there is a framework established to which further reforms might be attached, even if China’s domestic problems were a key inspiration.

Energy Synergy

The more concrete part of this story is China’s leading position in new energy technology, which touches on economics and politics at multiple points.

Geall says there is a growing strategic alignment behind “technology leadership, moving China up the value chain, making China a leading supplier of the technologies [to] supply power to the rest of the world [and] restructuring the economy away from heavy industry.” The fact is that there may be a large economic upside to dealing effectively with pollution.

China has for some years been at the forefront of investment in renewable energy. In 2015, a UN report revealed that China invested $102.9 billion in renewable power generation, more than the next three largest spenders—the US, Japan and the UK—combined. So “if you talk about leadership in terms of the highest value investment in solar and wind, [China has] been a leader for the last few years already,” says Ma.

The important part here is the state-led nature of China’s economy, which means that China has been able to cheapen new energy technology in a way other countries have not.

“In subsidizing and scaling up wind, solar, and lithium-ion battery technologies and enabling these technologies to fall rapidly in price… they are already competitive in many places for newly-added power generation,” says Anders Hove, Associate Director for China Research at the Paulson Institute in Beijing.

The overall situation, challenging as it is, has surprising synergy. In the first instance, China’s own thirst for energy has no discernible upper limit, save the level of pollution it generates, which is forcing it to move away from coal. Secondly, its desire to move up the manufacturing value chain and foster innovation has found a good outlet in renewables. Thirdly, the prospect of new markets around the world for home-grown technology is only going to grow exponentially, and lastly the possibility of greater energy self-sufficiency would always appeal to China’s very geopolitically-minded leaders.

It was the state-driven technology and manufacturing progress, Damien Ma thinks, that laid the foundation for all the other progress so far, as it allowed predictions of peak coal consumption, and the commercial logic of such a switch to encroach upon the realm of plausibility.

It could be that we are witnessing not the reluctant assumption of green leadership on the part of China, but the flowering of a longer-term strategy to support renewable energy technology. Fortunately for China, these renewable technologies have made faster progress than anticipated, providing China with a first-mover advantage when considering the global energy transformation anticipated by the Paris Agreement.

“China is already a clean energy powerhouse, and I expect export of clean energy technology and know-how—including policy know-how—to accelerate rapidly,” Hove says. “Promoting clean energy investment helps China’s exports, and dovetails with long-term efforts to win friends in developing-world countries.”

Policy Pinch

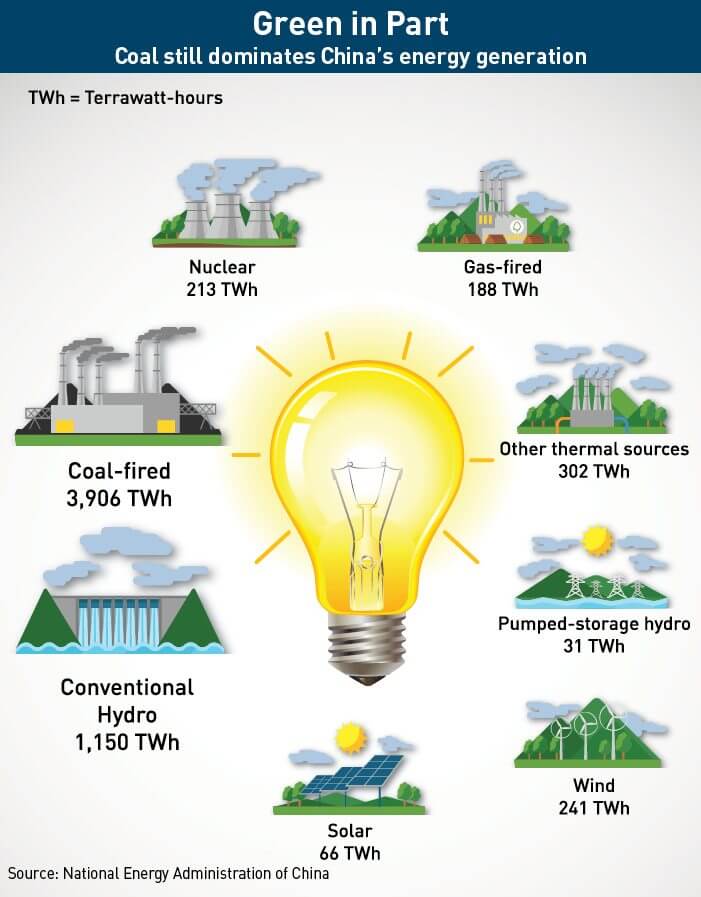

But for all these vaunting ambitions, there remain obstacles. In the first place, the contribution these technologies make to the overall energy profile in China remains small, just 13.3% in 2016, as opposed to 64% for coal-fired power. Moreover, China still plans to expand coal-fired power capacity by 19% by 2020.

Secondly, pollution-intensive heavy industries, such as steel, still comprises a very significant, although gradually declining, part of the Chinese economy. Furthermore, these heavy industries are dominated by old state-owned enterprises, which have until now served as the principal destination for growth-seeking stimulus.

Indeed, when discussing the scale of the recent smog problems in northern China, Ma makes clear that “there is a setback right now because they have been stimulating their economy,” revealing that, at a practical level, growth still displaces environmental progress when priorities clash. “It’s extraordinarily tough right now because they are facing a lot of downward pressure on the economy, and they are left with few good choices.”

A more complex problem with rolling out more and more renewables is simply that the electricity grid is not equipped to absorb it all, politically as well as in terms of infrastructure. Last year, China actually reduced its 2020 target for renewable energy by 27% largely because “the State Grid has their own ultra-high voltage technology and they want to connect to coal plants.”

As a result, much installed renewable energy capacity sits idle. The Jiuquan Wind Power Base in the Gobi desert of northwestern Gansu province hosts more than 7,000 wind turbines that can together generate enough power for a small country. And yet 60% of that capacity goes unused.

Nevertheless, China does have plans to upgrade its electricity grid, allowing lower voltage inputs to be distributed effectively, meaning this delay may be just a case of the grid not keeping up with the pace of renewables generation.

Meanwhile, Geall notes the significance of the recently announced “commitment to spend about $360 billion to 2020 on renewable energy, which should create about 13 million green jobs.” He suggests this can be interpreted as more than just a well-timed announcement but that “there are consistently ambitious policy statements coming out that certainly look like a bet on a low-carbon future.”

One drawback in the focus on energy generation, however, is that some other environmental issues have been sidelined. A study by the Chinese government last year, which surveyed 2,103 wells in eastern China, found that 80% of them were unsafe for drinking, and nearly half were unfit for human consumption of any type, including industrial use. Although China has announced plans to tackle this problem, there has been little if any improvement so far, and it gets nowhere near the media coverage that bad air gets.

But in the short term, these competing investment, growth and environmental priorities are, according to Geall, “precisely where the rubber’s going to hit the road,” meaning that structural difficulties remain to be overcome in China. However, he concludes optimistically that China is inevitably “going to be balancing those different impulses over the next few years.”

Burdens of Leadership

Aside from investment in renewables, leadership is often framed as influence over standard-setting and willingness to share a collective burden. Here, China has less of a track record.

Kai Olsen-Sawyer, Senior Research and Policy Analyst, at GRACE Communications Foundation, which promotes sustainable and renewable solutions for food, water and energy systems, suggests that China faces questions over its “transparency in greenhouse gas reporting, which is unreliable and may mask pollution.” He adds that “without trust in Chinese emissions reporting, skepticism about their actual reductions will remain, their credibility will erode and, ultimately, it could all hobble their ability to lead.”

Equally, Andre Brandao, Head of HSBC’s Climate Business Council, said in December last year, when reporting the results of an HSBC business survey, that “a low-carbon economy depends on a strong ecosystem for green financing and investment.” He went on to make the point that this requires moving towards “a framework for standardised climate disclosure [and] more production and consumption of climate research” which rather reinforces Olsen-Sawyer’s observations.

Green bonds, which help finance environmentally friendly projects, have however been on the rise in China. The country issued its first green bond in 2015, and last year issued bonds totalling $36.9 billion, about 40% of the total world market. But as in other areas, this may be less great than it seems. About one-third of China’s green bonds are up to China’s domestic standards of what kinds of projects qualify, but not up to international standards. For example, some of the bonds funnel money into so-called “clean coal” projects, which international standards reject as invalid.

Nevertheless, some are encouraged by China’s approach so far. Although a relatively new institution “the first round of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank projects have all been pretty positive and the standards they are using for lending are all the same as ADB and the World Bank etc.” says Geall.

Even if China merely manages to keep up with Western standard-setting, that will nevertheless have an enormous international impact, but in any event the Chinese clearly view leadership more in terms of investment and technology than in standard-setting at this stage.

Finally, recent hints from within the Chinese leadership indicate the possibility of a downgraded growth target, which will again reinforce the connection between high growth and low environmental standards, but may herald the acceptance of the idea that helter-skelter growth rates are perhaps as much part of the environmental problem as they are a solution to other strategic objectives. Damien Ma stresses that now “the growth target … is the overarching problem,” adding that “if they just relax that a little bit, that opens up a lot of room for other priorities.”

Opportunity Knocks

China’s official attitude towards environmental protection has clearly changed dramatically in recent years, but it will be a long time before the smog lifts. In this sense the idea that China will be a ‘Green Leader’ anytime soon says more about how far they have to go than how far they have come. Yet in recognizing their problems and directing investments towards new technologies, China has stumbled upon a realistic expectation of leadership in the energy technologies of the low-carbon future.

In policy and standard-setting, China still drags its feet, if only because it sees only the downside of making international commitments to do things that may prove difficult to implement—the Paris commitments, for example, are not binding. But in terms of investment, productive capacity and exports, China will inevitably be a ‘Green Leader’ because it is already way ahead.

Despite this, however, the scale advantages accrued by China’s sizeable early investments in green technology are dwarfed by the enormity of their problems right now. Because pollution is damaging people’s health, leadership has become an absolutely necessary aspiration for China, if only because they have so much ground yet to cover.