Dalian Wanda, one of China’s biggest property companies, has grown into an empire. But how stable is its future?

Dalian Wanda, one of China’s biggest property companies, has grown into an empire. But how stable is its future?

Among the many changes to China’s economy and society in recent decades, the privatization of housing since the late 1980s—which helped create a big part of China’s economic engine—was arguably the most pivotal. Dalian Wanda was born at the same time and has ridden the same wave to become one of China’s biggest companies.

Wanda is now a massive conglomerate, having spread far beyond its apartment block origins, but getting a clear sense of just how big it is, is difficult because most of it is not listed and financial information is sparse.

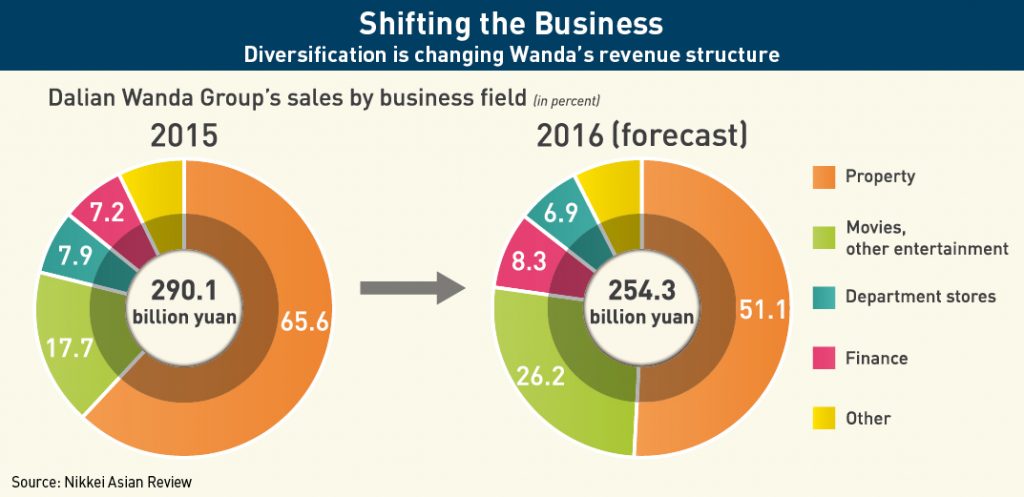

Wanda Group is owned by Dalian Hexing Investment Co., which is in turn owned by its founder, Wang Jianlin, now the richest man in Asia with an estimated net worth in 2015 of $30 billion. According to a statement by the company in January, the company’s assets were RMB 634 billion ($96 billion) in 2015, up 20.9% from a year earlier. Total revenue was $44.02 billion, up 19.1% from 2014, with 65.6% of that coming from the company’s Hong Kong property arm, Dalian Wanda Commercial Properties Ltd. The company has some 130,000 employees.

The Group came to global attention in 2012 via its acquisition of AMC Theatres, the second-largest North American movie house chain. It has since become a major force in the global movie industry not only with screens, but also production companies and a forthcoming studio complex in northern China that will be among the world’s most advanced.

Wanda is now also looking to break into the theme park business and opened up a $3.2 billion park in Nanchang just days before Disney inaugurated its $5.5 billion Shanghai operation, with which Wanda has an openly awkward rivalry.

“Disney really shouldn’t have entered the mainland,” Wang said in an interview on state-run CCTV in May. “We will make Disney’s China venture unprofitable in the next 10 to 20 years.” Wanda says it is planning 19 more theme parks in addition to the ones it already has.

In addition to theme parks, Wanda’s empire now includes ski resorts, broadcasting rights deals, property abroad, football teams, and even hospitals. In total, Wanda spent $15 billion in acquisitions last year, with both the scale and breadth of the expansion raising eyebrows—it is not clear where all that capital comes from.

“It’s a very aggressive level of diversification,” says Michael Cole, founder of the China real estate analysis website Mingtiandi. “Most companies are not going to say in a single year that they are going to make major new initiatives in a few different industries.”

At the same time, Wanda’s core property business is undergoing fundamental changes, partially switching from property development to property management, while its signature Wanda Plaza malls are in at least a few cases showing signs of stress. The company announced that it is expecting a 12.4% drop in revenue this year from 2015, the first ever decline in the company’s history, as income from real estate slows.

“I am quite negative on Wanda,” says David Hong, head of research at China Real Estate Information Corp, which provides data and analysis on China’s real estate market. “I don’t see that Wanda has a very good way [of changing the model].”

Whether or not Wanda can handle so many new ventures while at the same time shifting its core business is uncertain. But on the other hand, founder Wang Jianlin is among the most ambitious (and well-connected) businessmen in mainland China, and his track record so far is enviable.

Location, Location, Location

Wanda is very much a product of when it was founded, and of the founder himself. After 16 years as a soldier in the People’s Liberation Army, Wang left the military to set up Wanda with $80,000 of borrowed money in 1988, and his timing could not have been better. China had just started to create a private property market by devolving state-owned worker apartments to the workers, as well as beginning the sale of land rights to private builders. The development race was on.

According to The Economist, Wang built an early reputation in his hometown of Dalian by seizing the opportunity to redevelop the city’s slums into forests of apartment blocks. As the Chinese economy continued to boom, the company grew large in a property explosion that has financed local governments and created huge wealth for developers and buyers for much of the past 20 years. At the heart of it was the sale of land use rights by local governments to developers at cheap rates.

The nature of this system has for years fueled speculation about the importance of Wang’s relationships to Wanda’s success, suggestions he has batted away. Last year, The New York Times published the results of an investigation which, among other things, revealed stakes in Wanda Cinemas and Wanda Commercial Properties allegedly once owned by relatives of senior leaders.

Michael Cole puts it more succinctly.

“You don’t succeed in real estate in China without having good relations with the government, because all land comes from the government,” he says. CCTV, China’s state-run television network, has twice named Wang “Economic Person of the Year.”

By 1992, Wanda was incorporated and became one of the first shareholding companies in post-Mao China. In 2002 the company opened its first Wanda Plaza, a chain of malls which became its signature development and a key business driver—the 100th Wanda Plaza was opened in Kunming in 2014. In December of that year, the company took most of its property business public in the form of Dalian Wanda Commercial Properties on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, raising $3.7 billion dollars. It was the largest listing in the world ever by a real estate company at the time.

But Wang has not limited his company to the real estate and property industry, for both business reasons and to satisfy his enormous ambition. In a CNN interview on July 4, 2014, Wang said, “Our goal is to make Wanda a brand like Walmart or IBM or Google, a brand known by everyone in the world, a brand from China.”

Diversification

Wanda’s company name, in Chinese, roughly translates as “all things are achievable,” and in the past few years the company has more than lived up to that ethos, pushing into one venture after another.

Major diversification efforts began in the mid 2000s, with the company creating a focus on the tourism and cultural industries. In 2012, Wanda invested about $3 billion in the Changbaishan International Resort, a ski park located near China’s border with North Korea. Although ski culture in China is still nascent, the investment is expected to pay off following the Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022.

Already a household name in China, Wanda started to gain visibility in the West when it acquired AMC Theatres for $2.6 billion dollars in 2012. Since then, it has expanded its cinema holdings further snapping up Carmike and Hoyts, in the US and Australia respectively, making it the world’s largest cinema operator, a strategy that has been questioned by some industry observers.

“Most investors have not been [keen] about movie theaters in the US, or other developed markets for many years,” says Cole, citing historically declining attendance.

On the flip side, however, China’s domestic movie industry has been doing very well, with insiders and commentators this year predicting that it will become the new Hollywood. Likely for that reason, Wanda purchased Legendary Entertainment, makers of the film Jurassic World—in January for $3.5 billion. And the company is also spending $8.2 billion on Wanda Studios Qingdao, set to open in 2017, as one of the largest and most advanced production set complexes in the world, complete with a permanent underwater stage. (Wang arranged for some of Hollywood’s biggest stars, including Leonardo DiCaprio and John Travolta to be present at the 2013 project launch.) Sports have caught the eye of the company as well. In February 2015, Wanda paid $1.2 billion to buy Infront Sports & Media, which holds broadcasting rights in Asia for the FIFA World Cup, and the Basketball World Cup. A month earlier, it acquired a 20% stake in football club Atlético Madrid for $48 million. Later in August, it bought Ironman Triathlons for $650 million.

There are other giant Wanda investments almost everywhere you look. In January, it announced at $2.3 billion joint venture to build private hospitals across mainland China. In 2015, Wang Jianlin met with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to announce $10 billion in investment in India over the next decade to build hospitals, airports, schools—more or less entire towns.

“One thing you’ll notice about Wanda is the sheer volume of announcements they make… virtually a major announcement every week,” says Cole, who is a bit skeptical about the follow-through on many of these projects. “There is a lot of PR in that PR.”

David Hong agrees, noting that a large degree of diversification and a lot of hot air is somewhat common among China’s big property companies.

“Developers try to say a lot of stories,” he says, pointing to a lack of progress on many of them. “I think diversification is only a story until they make some real implementation.”

Theme Park Ambitions

But the scheme that has attracted by far the most attention recently is Wanda’s efforts to break into the theme park industry. Just before Disney cut the ribbon on its highly anticipated $5.5 billion Shanghai park this summer, Wanda opened up its own $3.2 billion attraction in the inland city of Nanchang, 730 kilometers west of Shanghai. But what has attracted people most so far isn’t the park, but Wang Jianlin’s derogatory comments on Disney in the lead-up to the opening.

“The frenzy of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck and the era of blindly following them have passed,” Wang told media in May. “[They are] entirely cloning previous IP, cloning previous products, with no more innovation.”

Ironically, a gaggle of Disney-owned characters, including a Star Wars Stormtrooper, showed up at the Wanda park opening, about which Disney promised to take action. Cole of Mingtiandi downplayed that aspect, citing the presence of third-party vendors, but did look askance at Wang’s general approach of attacking Disney.

“Let’s say, it’s an unusual strategy,” he says. “Generally when you are trying to promote your project you don’t devote too much time talking about your competitors.”

While the theme park is not Wanda’s first—the company opened Wanda Xishuangbanna International Resort in Yunnan Province last year for $2.5 billion—they are still new to the business overall. And they have announced plans for 19 more parks, including five outside China, although the locations have not yet been announced. The company already broke ground on at least one of the domestic parks, another $2.5 billion venture near Guilin in China’s southwest. The park is expected to open in 2020.

The sheer scale of these plans has left some skeptical about their ability to follow through. But Dennis Speigel, founder of International Theme Park Services in the US, takes a longer view. Speigel and his company have worked on theme parks in 50 countries, and helped create the business in China from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s.

“They are building at the right time, particularly with the large emerging middle class,” Speigel says, recalling that other companies have successfully broken into theme parks from zero experience in the past, notably Six Flags, the American theme park chain founded in 1961, which now has 19 locations in North America. “The market is there, the people are there… one common denominator that I have found in my 45 years is everybody wants to have fun.”

In terms of the development of the theme park industry, China could be entering its boom years. According to Speigel around 80 parks are currently being built around the country, so the competition will be stiff. In addition to Disney, Six Flags is aiming to open up Six Flags Haiyan, a $4.6 billion park in Zhejiang province just 45 miles from downtown Shanghai, in 2019.

However, having been in the industry so long, Speigel anticipates that although Wanda will face a lot of hurdles—learning “how to build the plane,” as he puts it—they will ultimately be successful.

“These guys are tenacious taskmasters with tremendous vision,” he says, noting also the mountains of money being spent. The a vision aspect is, of course, reminiscent of the patron saint of theme parks himself, Walt Disney.

Risk Guesstimation

But behind all the flash and headlines over acquisitions and resorts, Wanda’s core property business is looking a bit shaky, a fact that Wanda has been open about. Wang Jianlin himself said in January that it could take four or five years for the market to absorb unsold housing stock in tier three and four cities, which is the primary reason for the sales decline in many Mainland markets this year.

The Chinese property market is unquestionably experiencing some broad changes. According to David Hong, the market in tier one and two cities is strong, but margins have dropped from 40% to 20-25%. Anywhere else, is difficult to make a profit at all because of the vast oversupply. But while switching away from those cities may be a good thing for Wanda, Hong sees a different problem: inconsistency.

“In 2011 they say they all want to move into tier three and tier four cities,” he says of Wanda and many of its peer developers. “2013, they are thinking [that] going into tier three and four is stupid, and they say now we need to go back to tier one and two.”

The companies performing the best, he says, are the ones that have stuck to a single business model.

But perhaps a bigger uncertainty is the future of the ubiquitous Wanda Plazas, which helped make the company a household name in China. The group is beginning to use a so-called ‘asset-light model,’ which involves selling off the actual property, but continuing to derive revenue via management fees. The strategy is intended to limit risk exposure, but it also limits the upside.

“The biggest profit for developers is land appreciation and housing appreciation,” says Hong, noting that Soho has also tried this strategy and took a stock hit as a result. “I think the capital market will not give the same valuation as previously.”

Then there are the malls themselves, which Wanda continues to build despite an overall slowdown in retail sales. One source, who wished to remain anonymous, but who worked for a retailer opening anchor stores in about 100 Wanda Plazas, said that the company’s malls have dropped in quality and many are now poorly managed. According to him, some malls were even skimping on basic services such as air-conditioning in the summer to save money.

Hong was similarly blunt about quality: “If you visit those [Wanda Plazas] in tier three, four, and even in tier two cities, I think that you see there is no function at all, and no one is visiting the shopping center at all.”

Similar factors prompted credit rating agency Moody’s to change its outlook for Dalian Wanda Commercial Properties, the Hong Kong-listed real estate arm, to negative in February, which reflects its concerns over the company’s increased execution risk and weakening credit metrics and liquidity.

“In the past they [had] a very big property development portfolio which can help them to generate good cash flow to support part of these funding needs,” says Kaven Tsang of Moody’s, who is Moody’s lead analyst for Dalian Wanda Commercial Properties.

In other words, the company will likely have to rely on more debt in the future. But Tsang noted that Wanda’s property arm’s debt leverage remains appropriate for its investment grade rating. Moody’s, however, only assesses the property subsidiary and not the entire Dalian Wanda Group.

In fact, taking stock of the entire business is more or less impossible, which could easily become a source of stress for investors.

When asked where it came up with the $15 billion for last year’s buying spree, and the additional $3.5 billion and $1.1 billion for Legendary and Carmike this year, the company replied, “We have various means other than borrowing.”

Liabilities are a similar mystery, with a US analyst telling Nikkei Asian Review in March, “It’s a complete black box.”

Add to this Wang’s recent efforts to take the Hong Kong-listed property arm private, a surprising move given it has not yet been two years since the 2014 blockbuster IPO. The reason is ostensibly to re-list on the mainland because the stock price in Hong Kong has underperformed expectations.

But relisting is a difficult process in China with a long queue, and Wang initially had trouble reaching an agreement with stockholders, even after including a promised share buy-back if a relisting didn’t happen within two years. However, The Wall Street Journal had reported on August 15th that shareholders voted to accept a $4.4 billion buyout—a 10% raise on the previous offer. Still, it far from clear that the move is a net positive for the company.

“From a credit perspective [delisting] could be negative,” Tsang says. “First of all, delisting could mean that they are not required to comply with the listing rules before any relisting, and secondly, the information disclosure or transparency could be lower.”

Too Big to Fail?

But despite various concerns, real estate is still an incredibly lucrative business on the Mainland.

“The China property market is still one of the most profitable markets among all the industries in China or even in the world,” says Hong. “If you look at the top 100 players, almost all of them are making profits. Whereas if you look at all other industries, many of them for example, like TMT (technology, media and telecommunications), only the leaders break even.”

And Wanda has another strength as well, given the relationship between the property business and the state in China.

“Most of the major revenues of the local governments, especially for the lower tier cities, they all rely heavily on land sales,” Hong explains. “Because of this they are likely to [help] those developers that they previously supported, that go into any kind of financial difficulties.”

The anonymous source, who has met Wang Jianlin in person, put it a bit more directly.

“The only way they can really disappear is if they fall into political disgrace.”