Regulators have suspended IPOs on China’s stock markets. What’s their strategy, and how will it affect Chinese companies?

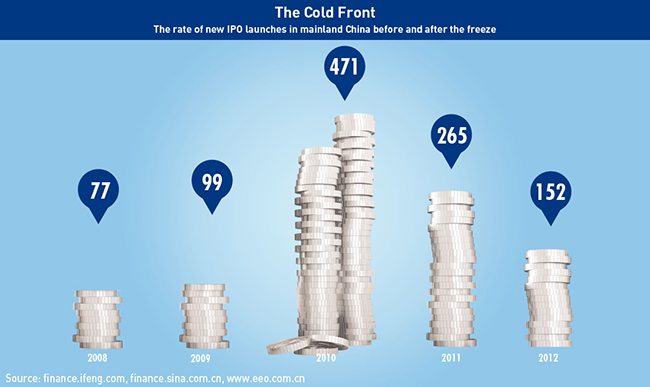

To a casual observer, the recent behavior of Chinaʼs financial supervisor might seem a bit odd. In June of last year a petition began circulating online that demanded the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) slow the pace of initial public offerings (IPOs) launching on Chinese stock markets. The rapid pace of new listings, it argued, was impoverishing existing shareholders. “Behind every retail investor stands a family that has been deeply hurt by unending IPOs and poor stock performance,” the statement said.

The CSRC seemed unmoved by the plea. In an official online discussion with investors the agency dismissed calls to slow the flow of IPOs, instead emphasizing that it was committed to moving in a more market-oriented direction. That meant less interference in the IPO process, not more.

Yet just a few months later, the CSRC reversed course. Approvals for companies to list on Chinaʼs three mainland stock exchanges—the Shanghai, Shenzhen and ChiNext boards—first slowed, then stopped. The last IPO to launch on a mainland bourse was in November 2012. Why did the CSRC suddenly have a change of heart?

The answer to that question could have profound implications for Chinese businesses. The immediate focus is on when the CSRC will allow IPOs to resume, and whether Chinese companies will turn to stock markets outside the Mainland—especially Hong Kong—in the meantime. But in the long term, the freeze illustrates the CSRCʼs efforts to change both its responsibilities and the process of going public in China—as well as its struggle against forces opposing those reforms.

“I clearly see a regulatory transition,” says Chen Long, Professor of Finance at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. “But it involves a lot of obstacles and a lot of political pressure.”

In Search of Lost Returns

Chinaʼs stock markets have experience a dismal past two years. The benchmark Shanghai Composite Index fell 25% between April 2011 and April 2013, and the broader CSI 300 Index dropped 23%. These declines come even as Chinaʼs economic growth has hovered around 7.5-8% and equity markets in other parts of the world have touched record highs.

Many investors chalk this performance up to the CSRC. By allowing the supply of IPOs to outpace investor demand, they claim, the regulator drained liquidity from existing shares and pushed down prices across the board. Hence the public pressure—from individual investors, investment funds, and others—to restrict IPO approvals in order to allow the market to recover.

Their petition may evoke a degree of sympathy, but skepticism is in order. Investors and listed companies are in effect asking the government to rig the market in their favor. Besides, the idea that new IPOs suppress the value of existing shareholders is “just plain wrong,” says CKGSBʼs Chen. Studies of global markets have failed to demonstrate a link between more IPOs and lower stock prices, he adds. While mainland China is unique in the degree of control regulators exercise over IPO issuance, in general, research seems to indicate the opposite relationship: lots of companies launch IPOs during bull runs, and hold off when the market turns sour.

While the CSRCʼs reluctance to slow IPO approvals was well-grounded, many officials appeared to be swayed by investor pleas, along with a desire to address legitimate concerns about shoddy accounting and corporate governance. They may have more or less forced the organization to impose the freeze against its will. “The decision was probably a combination of the stock market not doing well and complaints about corporate governance and bad financial information,” says Chen. “[The CSRC] was under a lot of pressure to do this.”

Making a List

In any event, the CSRC has taken the opportunity to clean up the listing process with an aim to revive investor confidence in the quality of future issues. In January it ordered underwriters—firms such as Citic Securities, Guosen Securities, Haitong Securities and many others—to review the financial year 2012 earnings of the almost 900 firms waiting in the queue to list, after which it would select 30 via lottery for an intensive audit. The unspoken expectation of companies was those that saw profits decline last year would withdraw their application.

By April 3, shortly after the deadline for self-reviews, 162 firms had voluntarily terminated their bids and another 107 requested deferrals. That left 612 firms still in the dock for listing. The deferred companies were granted until the end of May to produce results, after which another 10 would be chosen for inspection.

By all accounts, the CSRC means business. An anonymous investment banker uploaded a picture on Sina Weibo showing more than 25 boxes of company documents collected by regulators and warned of “sleepless nights” ahead. Peter Fuhrman, Chairman of the investment bank China First Capital, described on his blog rumors that the CSRC had begun videotaping interviews with company bosses and hired a team of facial analysis experts to spot lying executives.

Moreover, tales abound of companies that opted for deferral and are now locked in battle with their underwriters. Some of these firms had been due to list in late 2012 and did not anticipate they would have to post higher profits last year. They may be under pressure to cut corners on accounting in order to stay in the queue, gambling that they will not be selected for a CSRC audit, says a professor at Peking University who asked not to be named because he occasionally advises the regulator. Company underwriters, by contrast, are well aware that the CSRC could effectively shut them down if they are complicit with a falsified report.

“They are now applying significant pressure to [their clients] to remove themselves from [the CSRC IPO approval] list,” the professor adds.

That tension may be precisely what the CSRC is looking to generate. Multiple sources say the regulator is using the self-review process in part to emphasize that underwriters are liable for the financial statements of the companies they handle, thereby shifting the burden of enforcing compliance away from the CSRC and investors and on to investment banks. That approach is similar to reforms the Hong Kong exchange pushed through in recent years, notes Philippe Espinasse, a Hong Kong-based former investment banker and author of IPO: A Global Guide. While Hong Kong has generally high disclosure rules, a handful of IPO stumbles spurred regulators to strengthen standards.

“The main way they decided to do that is to put the onus [of due diligence] on the banks,” says Espinasse. “The CSRC is also trying to create more financing options for the economy in general,” says Anthony Skriba, Director at Z-Ben Advisors, a financial consultancy.

He notes that Chinese brokerages are much more reliant on IPO underwriting fees than international brokerages, and have been reluctant to invest heavily in alternative financing options. The freeze is forcing them to diversify their revenue streams, which should in turn lay the groundwork for the governmentʼs broader goal of developing a more diverse financing environment for Chinese firms seeking capital.

Looking for an Alternative

To that end, the CSRC has been actively encouraging Chinese companies frustrated by the freeze to explore options such as off-exchange equity markets, bond markets and equity markets abroad, reported China Securities Journal, a state-run news outfit with close links to the agency.

Some of these alternatives are not yet ready for prime time. Over-the-counter (OTC) equity markets are still immature and lack the capacity to absorb a stream of new issues. Chinese firms will likely avoid the bond market as well, if only because they prefer to raise capital via equity than be saddled with debt.

Listing abroad, however, can be an attractive option. This is particularly true after the CSRC announced in late December that it would scrap minimum requirements on net assets, annual profits and fundraising targets for Chinese firms listing abroad.

Of course, Chinese companies have already been exploring various foreign markets. US markets are effectively closed to Chinese firms after a series of short-seller attacks and downturn in investor sentiment, but Frankfurt on the other hand boasted seven Chinese listings last year. Other niche markets such as South Korea, Malaysia and Australia host the occasional Chinese IPO. At least one Chinese company is even considering listing on the Stockholm Stock Exchange, according to a Beijing-based financial consultant who asked not to be named because he is covering the deal.

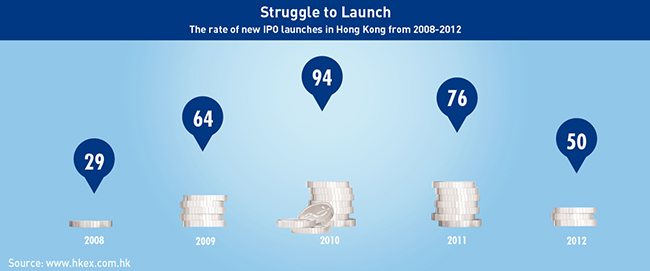

Yet by far the best-placed exchange to capture spillover from the IPO freeze is Hong Kong. Some 80-90% of the marketʼs IPOs hail from mainland China, and at least 10 large mainland firms have recently expressed interest in listing there by summer 2013, with combined fundraising targets of around RMB 50 billion ($8.1 billion). Chinese state media has claimed some of these decisions are directly attributable to the IPO freeze.

Hong Kong has plenty to offer Chinese firms, from liquidity and professional services to a general familiarity with the mainland. A few mainland IPOs have done well by listing in Hong Kong over the past few months. Perhaps the most notable example is Peopleʼs Insurance Company of China (PICC), which launched a $3.1 billion IPO in December 2012. Share prices popped significantly on the first day of trading and remained high more than five months later.

Yet PICCʼs performance stands out as an exception, and those in the industry say Chinese companies will probably not turn there en masse.

“Iʼm really skeptical that weʼre going to see a wall of Chinese IPOs coming to Hong Kong [because of the freeze],” says Espinasse, the former investment banker.

Chinese regulatory hurdles to listing in Hong Kong are still a factor, market valuations are fairly low, and new listings have fallen dramatically over the past couple of years. As of mid-April, the exchange had raised just over $1 billion in new listings, putting it behind smaller bourses in Thailand and Singapore. Of those new issues, well over half were trading below their IPO price.

Part of the reason for the low valuations is that many mainland firms encourage underwriters in Hong Kong to compete based on the size of the cornerstone investment they are able to lock in, says Espinasse. That may sound like a good incentive in theory, but in practice some degree of coordination between banks is necessary to prevent key investors from being put off by multiple pitches for the same listing.

Moreover, many of the cornerstone investors for mainland Chinese IPOs are not traditional institutional investors but personal friends and family of the Chinese company.

“They place their orders and it means the IPO gets done—but these guys are not natural buyers in the market,” says Espinasse. “You therefore end up with IPOs that fall in the aftermarket.”

Still, he remains optimistic that deals can get done even in the current investor climate.

“Thereʼs a lot of cash moving around [the market] that is looking to be put to use, and when you have [Chinese] companies that need that cash, theyʼll meet at some point,” says Espinasse. Then it comes down to pricing—Chinese companies may have to offer substantial discounts to lure Hong Kong investors, he adds.

Paradigm Shift

For that same reason, however, most Chinese companies will probably opt to stay at home. Valuations on mainland markets are substantially higher than other exchanges in large part because the CSRC has tightly controlled how companies are listed and de-listed, says CKGSBʼs Chen. Particularly before 2009, the agency not only vetted accounting records, but also company outlook and valuations. The upshot is that very few IPOs have failed in China. But tightly restricted supply also meant that listed firms were valued about 20% higher than their unlisted peers by the end of their first day of trading, says Chen.

“Even the shell of a [listed] company is worth something, because itʼs very hard to get listed and de-listed,” he adds.

Chinese companies therefore have an incentive to simply wait for the freeze to end, which many traders reckon will be after CSRC audits are completed—likely sometime around June or July, reported Bloomberg. But they would do well to keep in mind that current market dynamics may not last forever. The CSRCʼs long-term goal, said Chen, is to move towards a system similar to Western stock markets, in which companies can easily list and be de-listed. Under such a system, the queue for IPOs would evaporate—along with the premium for listed firms.

“[The self-review process] signals the transition of authorities to convert from the current ʻinvestigate everything about the business modelʼ system to one that just verifies the quality of [company] information,” said Chen. “Thatʼs the direction itʼs going in the long run.”

That might not please investors petitioning to rig the market, or listed companies that benefit from todayʼs high valuations. But it would certainly be good news for future Chinese companies looking to raise capital and expand business.