China’s incubators set entrepreneurial spirit in motion.

Stephen Bell has high hopes for Chinese student entrepreneurs. The American venture capitalist invests in seed-stage start-ups across China, betting that the next Mark Zuckerberg will emerge from the world’s second-largest economy.

Bell’s Beijing-based venture-capital firm Trilogy VC runs the ChinaStars incubator program at the country’s top universities. Participants have 90 days to build an original consumer Internet, mobile, game, or new media product. The product Bell judges to be best at the end of the three-month period receives two years of funding from Trilogy Ventures.

“There’s a myth in this business that experience matters,” Bell says. He believes the unconstrained imaginations of young entrepreneurs often convert the best ideas to winning products—“when they don’t know they can’t do it”.

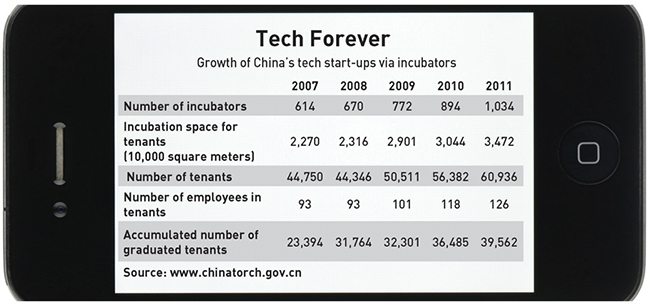

If China’s overall private sector remains “in retreat”, reaping scant benefits from mercantilist economic policies that favor state-owned giants, then technology start-ups buck the trend for now, their success buoyed by low capital requirements and China’s surplus of programming and engineering graduates. A vibrant scene has sprung up in Beijing’s Zhongguancun—“the Silicon Valley of China”.

According to 17Startup, a website that collects data on Chinese start-ups, nearly 3,600 start-ups were founded in China in 2012, and more than half were e-commerce or mobile Internet companies. Among them were the Changba mobile karaoke and Papa photo-sharing applications, the former which boasts user numbers in the millions. Mobile and e-commerce firms secured more than 50% of the total investment in start-ups. Still, overall, less than 5% of the start-ups received investment.

Incubators can help fill that void by injecting capital into cash-starved young companies. At the same time, with Chinese start-up culture still in infancy, incubators have the potential to play a larger role in shaping the industry landscape than in the West, helping to build an enduring start-up ecosystem made in China.

Although China’s conservative society still largely frowns on start-ups, viewing them as inferior to a stable job with a major company, things are changing fast thanks to the work of ambitious incubators, says Kevin Lee, Chief Operating Officer of China Youthology, a Beijing-based market-research firm that tracks trends in Chinese youth culture. “Incubators are making market-based entrepreneurialism mainstream and accepted here,” he says. “They give young entrepreneurs who are not well-connected or wealthy the chance to transform an idea into a working product and business model and then they help them launch it.”

Lee believes incubators can help fill a void created by the Chinese education system, providing a platform to develop the cross-functional skill sets essential to the success of entrepreneurs in the West. “In China, you have to sacrifice everything else to have great tech skills, but bringing a product to market is not just about how well you can program,” he says.

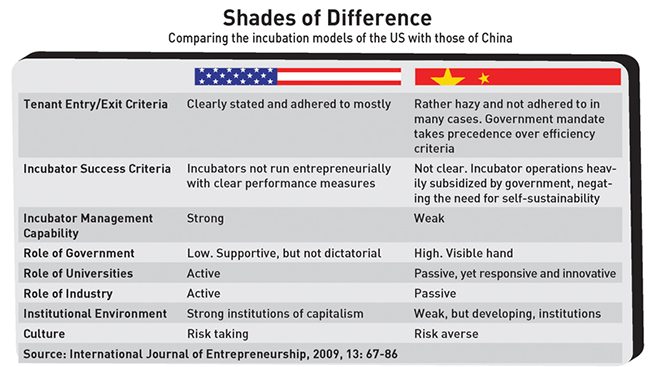

Incubators in China provide far more resources to start-ups than their counterparts in the US, says Kevin Der Arslanian, an analyst with China Market Research Group, a Shanghai-based consultancy. “It is much more of an accompaniment process in China,” he says, important in his view because Chinese law requires companies show three years of profitability before they can list. The heralded Innovation Works incubator, founded by ex-China Google chief Kai-Fu Lee, provides start-ups with in-house designers, office space and legal consultants in addition to capi-tal. With a nine-month incubation period, start-ups in Innovation Works also have three times as long as their Silicon Valley counterparts to bring a product to market. When they do, they can use the Innovation Works name to gain wider brand recognition in the market.

But not all China-based incubators have long incubation periods. Stephen Bell’s ChinaStars and Dalian-based Chinaacclerator both graduate start-ups in 90 days like the typical Silicon Valley model.

Start-ups in the Jue.io incubator, which manufactures technology accessories like iPhone cases and specialized key chains, have access to Jue.io’s trusted distribution network and production facilities, streamlining the manufacturing process.

Mentorship forms another cornerstone of the capabilities of China’s incubators. The Dalian-based Chinaccelerator incubator, which bills itself as “the first mentorship-driven seed-funding program in China”, has more than 60 mentors available to assist its start-ups, among them Brad Higgins, former Chief Financial Officer of the US Department of State, James Tan, Founder and Managing Director of the leading Chinese venture-capital firm Quest VC, as well as Stephen Bell. Chinaccelerator is a network partner of the US-based TechStars incubator, which was founded in 2006.

“Powerful mentors are rare in China,” says Josh Ong, tech-industry watcher for The Next Web site. “Guidance and insight to aid a start-up in overcoming challenges are some of the most important services an incubator can provide. It helps start-ups understand the value they can bring to the ecosystem.” Having world-class mentors onboard also boosts the incubator’s prestige, helping it to build its own products and brand, Ong adds.

Incu-greater?

High-profile China incubators typically begin by borrowing a page from the Silicon Valley handbook. Lee of China Youthology describes a trajectory of “fast ideas, fast iteration, fast testing and fast scaling.” Bell’s ChinaStars and Chinaccelerator graduate start-ups within three months of incubation. Ex-Google China chief Kai-Fu Lee’s Innovation Works, the biggest China-based incubator, initially followed a similar model, although it now focuses on later-stage incubation.

Der Arslanian of China Market Research Group, believes Kai-Fu Lee established the incubator model as credible in China. In his view, Lee, having previously served in executive roles at Apple and Microsoft, used his IT industry prowess to establish a viable model for China-based incubators and made them mainstream. “Before Innovation Works, incubators did not enjoy the same reputation,” Der Arslanian says.

According to the TechinAsia website, as of last September, Innovation Works had incubated 50 start-ups since its inception in September 2009, with a total investment exceeding RMB 3.9 billion (more than $615 million). Innovation Works selected those 50 start-ups from a pool of more than 5,000 applicants. The greatest success story thus far is Wandoujia, or SnapPea in English, a third-party Android sync management app and app store that helps users to manage their smartphones and tablets from their computers. Billed as “Android’s best friend,” Wandoujia software had exceeded 30 million installations in China as of June 2012, about 50% of the nation’s Android users. It went global the following month.

But SnapPea’s success overseas is far from guaranteed, says Der Arslanian. He adds: “It is an application that is very specific to the Chinese market.”

Of the 37 start-ups Stephen Bell’s Trilogy has funded in the past few years, eight are profitable. Droidhen, an Android game developer, is present on half of China’s Android phones. JiaThis, which lets users share information over Chinese social networks, also has strong prospects.

The most recent product to emerge successfully from the ChinaStars incubator is Weidanci, or Wikiword in English, which Bell describes as “a Chinese Wikipedia for dictionaries”. Available in web and Android versions, Weidanci allows users to add their own definitions of words in Chinese and English. It has become popular with students, who have added sections pertaining to different tests they take. The team of Beijing University Science and Technology graduate students that created Weidanci received two years of funding from Bell, Nearly RMB 1 million, which he says will last them for two years.

The Next Zuckerberg

Bell believes the next revolutionary tech start-up will emerge from China. “The pace of change is faster here than anywhere in the world,” he says, adding that young Chinese entrepreneurs are “incredibly creative”. In Bell’s view, Facebook revolutionized social networking because “it was the latest and best way for people to keep in touch with their friends”. Similar to Apple, Google and Microsoft before, Facebook “was 100% focused on turning out a great product,” he adds. “Could China produce the next Mark Zuckerberg? The odds are high based on population,” says Ong of The Next Web. Bell’s challenge, Ong believes, lies in the Chinese education system, which “is not designed to cultivate innovation”.

Culture matters enormously, in the view of Howard Yu, a professor of management at the Switzerland-based business school IMD. American popular culture has long enjoyed popularity overseas, he says, which helped Facebook quickly gain a global following. Chinese culture, which remains esoteric to much of the world outside of Asia, could constrain the potential of a Chinese Facebook to catch on with the international market, he said.

For his part, Kai-Fu Lee remains skeptical about a Chinese Zuckerberg. Differences between the Chinese and American educational systems, Internet markets and general societies mean that Chinese venture capitalists favor a more mature, execution-oriented entrepreneur. This Chinese entrepreneur aims for success, but may think more in the mainstream, Lee said, in remarks to the audience at the Boao Asia Forum held in Hainan last April.

The Price of Freedom

Despite the extensive resources incubators provide, the majority of Chinese start-ups still choose to go it alone. This was certainly the case with star performers of 2012 like Changba, the red-hot mobile karaoke app launched by the Beijing start-up Zuitao, founded by serial entrepreneur Chen Hua. Chen also co-founded the travel portal Kuxun which TripAdvisor acquired in 2009. Changba provides a licensed selection of 2,000 songs along with a virtual stage and audience for smartphones. Users can sing a song into the phone, save it, add a photo slideshow, and share it with the Changba community or their friends. Changba now reports more than 10 million users.

Papa, the photo-sharing application launched last year that allows users to record voice narrations to accompany their images, also has risen to success without the aid of an incubator. But according to Steven Millward, an Asia tech-industry watcher for the TechinAsia site, Kai-Fu Lee himself is a Papa user. Lee could potentially take Papa onboard if he believes the app has sufficient potential. Papa has already received an angel investment from Xu Zhaojun, whose Diandian startup—known as “the Tumblr clone of China”—has the backing of Innovation Works. While a good incubator “is a win for everybody”, when start-ups join, they do forfeit freedom and equity, says Ong of The Next Web.

Some incubators exist only in name, says Der Arsalanian of China Market Research Group, adding that “a company just renting office space to a start-up or taking a large amount of its stock is not an incubator”.

According to Charlie Custer, founder of ChinaGeeks.org, the benefits of joining an incubator may not outweigh the costs. Many start-ups have sufficient funding and office space, and would prefer not to give away substantial equity to join an incubator, he wrote on TechinAsia.

Beyond Tech

In the years ahead, industry watchers expect China’s start-ups to further expand beyond the tech field, which will necessitate incubators adapt their business models. “I find it exciting to look beyond tech,” said Lee of China Youthology. “Already, fuerdai [China’s wealthy second generation] kids are pooling their parents’ money together and investing it in things like NGOs, especially in the south of China.”

Lee believes these affluent young entrepreneurs, facing pressure from their social circles, are concerned largely with the prestige of their endeavors. “If there were a tech opportunity high on reputational impact, then fuerdai would be interested, but those kind of opportunites are rare,” he adds.

Kai-Fu Lee’s Innovation Works has already changed its business model considerably, analysts say, evolving from a Western-style incubator focused on early seed-stage investment to an organization specializing in late-stage incubation. For that reason, a startup like the Papa photo-sharing app that has already achieved a certain level of market penetration would be a contender to join. Innovation Works today has become more institutionalized, said Lee of China Youthology, with the addition of finance, marketing and organizational experts. “They copied the Silicon Valley incubator model first, and innovated later,” he said.

Professor Howard Yu of IMD predicts China’s strengthening of the rule of law will benefit incubators. As IP protection and the general arbitration environment improve, it will provide fertile ground for more sophisticated innovation, he says, adding that “a lot more business incubators will be popping up in the future”.

The market is maturing, Ong of The Next Web believes. In his view, Chinese companies, once notorious for cloning, are quickly becoming innovators in their own right.

In the meantime, while Chinese start-ups have achieved widespread success domestically, their international footprint remains negligible. At the OpenWebAsia 2012 awards held in December, which recognized the top 10 start-ups of the year in the region, not one of the companies awarded hailed from mainland China. The closest was Hong Kong. The rest of the winners were from Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore. Ironically, the event itself was held in Hainan Province.

What works in China may not work overseas, says Der Arslanian of China Market Research Group, adding that Chinese start-ups have little experience adapting hit products at home to foreign tastes.

In the view of Ong of The Next Web, that’s not a large problem, since Chinese start-ups remain in a nascent stage. It resembles the first Internet boom in the US, “a frontier in many respects, bursting with entrepreneurial energy,” he says. Ong believes incubators not only help start-ups get a product to market faster, but also foster a wider community-driven culture supportive of entrepreneurs.

Lee of China Youthology agrees. “The cultural impact is huge,” he said. “Incubators are making start-ups more acceptable in Chinese society.”

Yet ultimately, incubators’ ability to help cash-starved start-ups secure funding will determine the scale of China’s start-up culture, believes Der Arslanian. “At the end of the day, cash is king,” he says.