Last year, Zong Qinghou, founder and president of Wahaha, China’s biggest beverage company, was holding a run-of-the-mill press conference in Beijing. Although Zong was the richest man in China by some estimates, it seemed as though nothing of interest would come out of his speech that day. Then an ostensibly throwaway comment sent stocks soaring.

“We might buy out a Japanese dairy company. The Japanese are very hard workers,” Zong said. “In terms of milk production, their technology is outstanding.” That was all the reporters needed. Within a few hours, websites were posting the news:

“Chinese Beverage Giant Wahaha Eyes Japanese Dairy Firm Buyout.”

Zong didn’t name the company he was talking about. In fact, he spoke only a few sentences on the buyout. But that was enough to drive up the stock prices of Megmilk and Morinaga Milk, two of Japan’s biggest dairy firms. Buyers of Megmilk were particularly enthusiastic; shares jumped 7%, even after the company denied any knowledge of such a deal. As of now, Wahaha is not pursuing any acquisitions in Japan.

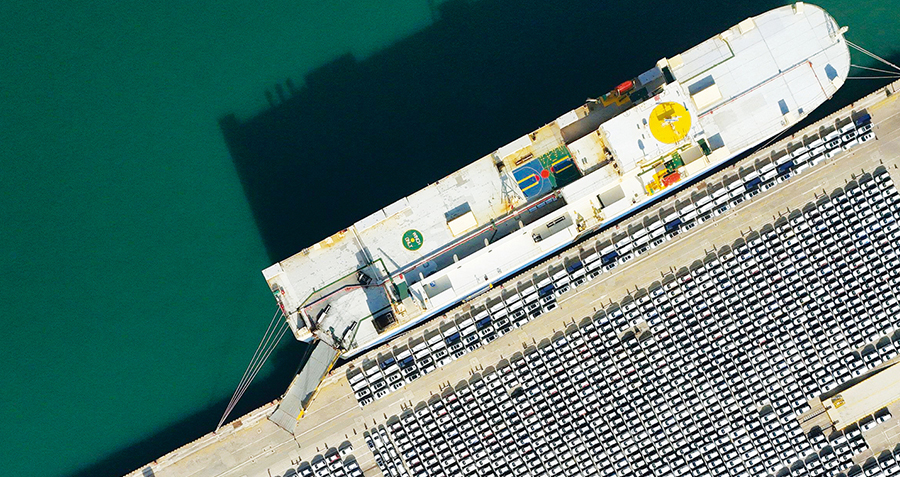

The moral of the story is more than “investors can be trigger-happy”. It’s that, five years ago, no one would have reacted to Zong’s press conference. That investors went wild last year means something more: Chinese companies are going abroad in force, and nowhere is that truer than in Japan.

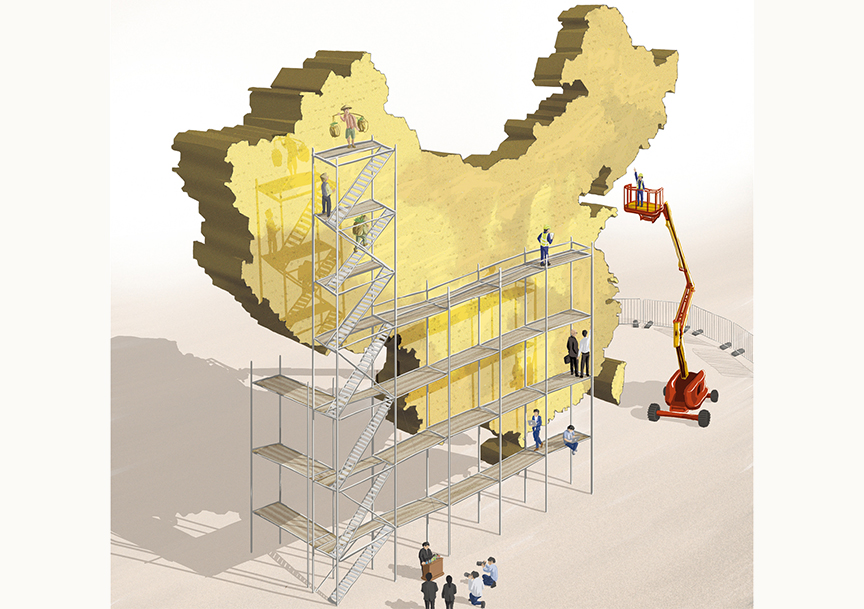

Chinese companies conducting M&A in Japan have seen mixed results, as evidenced by a new case study by Dr. Xiang Bing, Dean and Professor of Accounting at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. But before delving into the specific cases, it’s important to look at the first wave of foreign M&A into Japan to understand the challenges these types of takeovers present.

Not so Big in Japan

In January 1990, the bottom finally began to fall out on Japan’s real estate market. Stocks slumped, housing prices plummeted, businesses went belly up, and banks buckled under the weight of unpaid loans. In the succeeding years, Western companies and investors combed through the debris, seeking opportunities for mergers and acquisitions. By most accounts, they failed.

According to Dr. Daniel Duane, an investor who spent 30 years on Wall Street managing global investments for several major funds and investment banks, there were several reasons why.

“These investors had several common characteristics,” says Duane. “They had US-style activist investor skills, but no knowledge of Japanese customs or culture.”

This cultural ignorance proved fatal, according to Duane. The investors swooped in launching hostile takeovers, seizing complete control of companies, and taking on troubled firms and bloated conglomerates. These takeovers, Duane says, often meet with opposition from the Japanese workers and public.

But Duane says there was another crucial mistake the Western firms made: “They wanted to restructure, including changing management, laying off excess workers and streamlining operations, in order to restore them to profit.” For a society based on strict hierarchy and lifetime jobs, on seniority and stability, this was far too much to swallow. In the end, most of the Western investors either scaled back their plans or completely gave up on Japan.

China’s Turn

Over the last decade, however, as Western firms pulled out of Japan, Chinese companies have appeared on the scene. Have they fared better than their Western counterparts? The story of Suntech, one of the companies profiled in CKGSB Dean Xiang Bing’s recent case study, sheds some light on this question.

Shi Zhengrong was a typical returned Chinese scholar when, in 2001, he approached the Wuxi municipal government’s with a plan to start a company. Having earned a PhD in Australia under a scientist who won the Nobel Prize for research on photovoltaic (PV) cells, Shi was eager to launch China’s first serious solar contender.

Although installed solar capacity in China was virtually non-existent 10 years ago, the government saw potential in the PV manufacturing sector–and Suntech was born. At the beginning, Shi owned a quarter of the shares and the Wuxi government held the other 75%. As in the early stages of many industries that have shifted manufacturing to China, initially Suntech was able to compete on price due to the country’s low labor and production costs. Within three years, Shi’s firm had broken into the top 10 global solar enterprises in terms of generation capacity. In 2004, however, China’s first wave of mature PV companies began buffeting Suntech–low costs alone would not let the firm hold onto its country-leading position.

At the same time in Japan, the Koizumi government, known for pushing free market policies, suddenly withdrew their generous PV subsidies, which had helped make Sharp the world-leader in the solar space. Under new pressure to reduce costs, Sharp severed contracts with many Japanese component manufacturers and turned to foreign original equipment manufacturers, which were offering lower prices. MSK, a 50-year-old solar battery maker, was left in the lurch. With much of its revenue coming from its contracts with Sharp, MSK knew they were in trouble unless they could find a savior who would buy them out.

The business savvy Shi seized on the opportunity to take over MSK–not only did the Japanese firm have advanced technology for several components, but it could also it also give Suntech access to the massive Japanese market.

In 2006, Suntech snapped up the suffering MSK for $300 million. At the time, it was the biggest overseas buyout by a Chinese firm in history. Suntech’s stock price soared, and Forbes named Shi China’s richest man. But Suntech’s honeymoon in Japan wouldn’t last. While struggling to turn around MSK, the Chinese firm ran into many problems–everything from public opposition to infighting.

Growing Pains

The problem that underpinned everything else was the financial state of MSK. “One of the biggest mistakes Chinese companies make when conducting overseas M&A is that they go for giants, especially giants in deep trouble,” says Prof. Teng Bingsheng, Associate Dean of CKGSB’s MBA program and Associate Professor of Strategic Management. “Chinese firms don’t have a strong track record [in turning around failing firms].” As a privately-held company, MSK had no experience doing accounting for investors. Suntech had no idea what how troubled the company actually was.

One thing that became clear almost from the get-go was Suntech hadn’t done enough early stage research. Around 80% of solar batteries in Japan are sold to individual buyers for home use. In most other major markets, the vast majority of sales are to solar farms. For Suntech, this meant its products would now have to meet a whole new set of standards affecting everything from appearance to size. Suntech had to go through an entire product overhaul to appeal to this new market.

Further problems arose with MSK’s labor unions. Suntech realized that while the R&D conducted in Japan was high quality and worth the expense, the manufacturing was far more expensive than in China. When Suntech decided to shut down one of MSK’s factories and lay off the workers, it ignited a media firestorm and public outrage. In the end, the employees of the to-be-shuttered factory staged a coup. They exercised a right under Japanese law to buyout their factory, which they kept running in competition against Suntech.

Shi was apologetic, although intransigent. “No company wants to lay off workers, but we had to do it to keep the company alive,” he said to the China Economic Report at the time. “Japan’s lifetime employment system is actually a hindrance to many companies’ viability.”

Another major difficulty that Chinese firms face when trying to tap the Japanese market is prying open tightly sealed sales and supply chains. According to a report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 70% of Japan’s supply chain and logistics are controlled by an oligopoly of domestic conglomerates. MSK may have been a local company, but it was mainly a parts supplier. Sharp was responsible for getting its products to market–and it was going to help MSK now that it was owned by Suntech.

Here’s where Suntech got creative. After failing to go through the traditional sales channels, the company struck deals with home appliance stores and other retailers who didn’t normally sell solar batteries. This innovative way around the Japanese conglomerates has produced some success, but Suntech still has had trouble gaining a significant market share.

Clash of Civilizations

The last of the big challenges Suntech had to overcome is by no means the least–culture. Although MSK had courted Suntech’s purchase, the buyout was initially opposed by most of the shareholders. After several attempts to get more shareholders on board, MSK’s CEO finally threatened to resign if the deal wasn’t approved. The shareholders eventually acquiesced.

“This type of reaction is the by-product of being an island nation. The people are insular,” says Sarada Takashi, an analyst with Nomura Securities in Shanghai. “People see this as a threat to Japan, and the media often make matters worse.”

Despite the initial support of the CEO, he later became an obstacle to Suntech’s reorganization plan. The CEO firmly opposed many parts of the plan, especially the layoffs (Suntech would eventually layoff 20% of MSK’s Japanese employees). Shi was stuck. Unable to work around the Japanese CEO, Shi spent two years looking for a replacement. He finally brought on an executive from video game developer Sega who had considerable experience working at MNCs. More bottom line-minded in his management outlook, the new CEO was able to push through Suntech’s plan and MSK returned to profitability.

Six years after the takeover, Suntech is now the world’s leading PV manufacturer by installed capacity. This is in no small part due to its incorporation of MSK and the access it gained to Japan’s market. Unlike many of the Western firms in the early 1990s, Suntech learned to adapt and innovate rather than just give up. Obviously it wasn’t easy, but on this matter Shi has one last piece of advice: “Success comes from perseverance. Buying a Japanese firm is very difficult. But if you give up because you’re afraid of all of the challenges, you’ll be missing a great opportunity.”